Behind the Beautiful Forevers Summary

9 min read ⌚

Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity

Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity

Have you ever watched Slumdog Millionaire?

Well, this is a book about all the slumdogs who’ll never make it.

And, to quote Junot Diaz, it’s “beyond groundbreaking.”

Ladies and gentlemen, Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers.

Who Should Read “Behind the Beautiful Forevers”? And Why?

Behind the Beautiful Forevers is a book that anyone who wants to learn a little more about India should read.

It is also a book which should interest anyone who wants to learn something more about the causes and the outcomes of poverty, as well as the cancerous nature of corruption.

Finally, it is a book about all the people who believe that there are easy solutions to poverty-related issues; as always – it’s a lot more complicated than that.

And far more humane.

About Katherine Boo

Katherine Boo is an American Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist.

is an American Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist.

Winner of the 2002 MacArthur Genius Award, she has been a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine for the past decade and a half.

Boo’s only book so far, Behind the Beautiful Forevers won her numerous awards, including the National Book Award for Nonfiction.

“Behind the Beautiful Forevers Summary”

Behind the Beautiful Forevers is a panoramic portrait of the lives of several residents of the Annawadi slum of Mumbai, located on the e Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport.

The location was initially settled by migrant workers who had come to work on the airport in the 1990s. The place they claimed for themselves (though unusable at the time) belonged—and still belongs—to the airport.

In less than a decade, it grew into a loud and densely populated slum inhabited by people coming from all over India and Pakistan.

Katherine Boo visited Annawadi several times during the course of three years, and interviewed many of its residents.

In Behind the Beautiful Forevers she shares her findings—most of them related to the numerous problems and fears the people living in Annawadi face on a daily basis.

What kind, you ask?

Well, allow us first to introduce you to the three main groups of characters.

And then to tell you their dreadful intermixed stories.

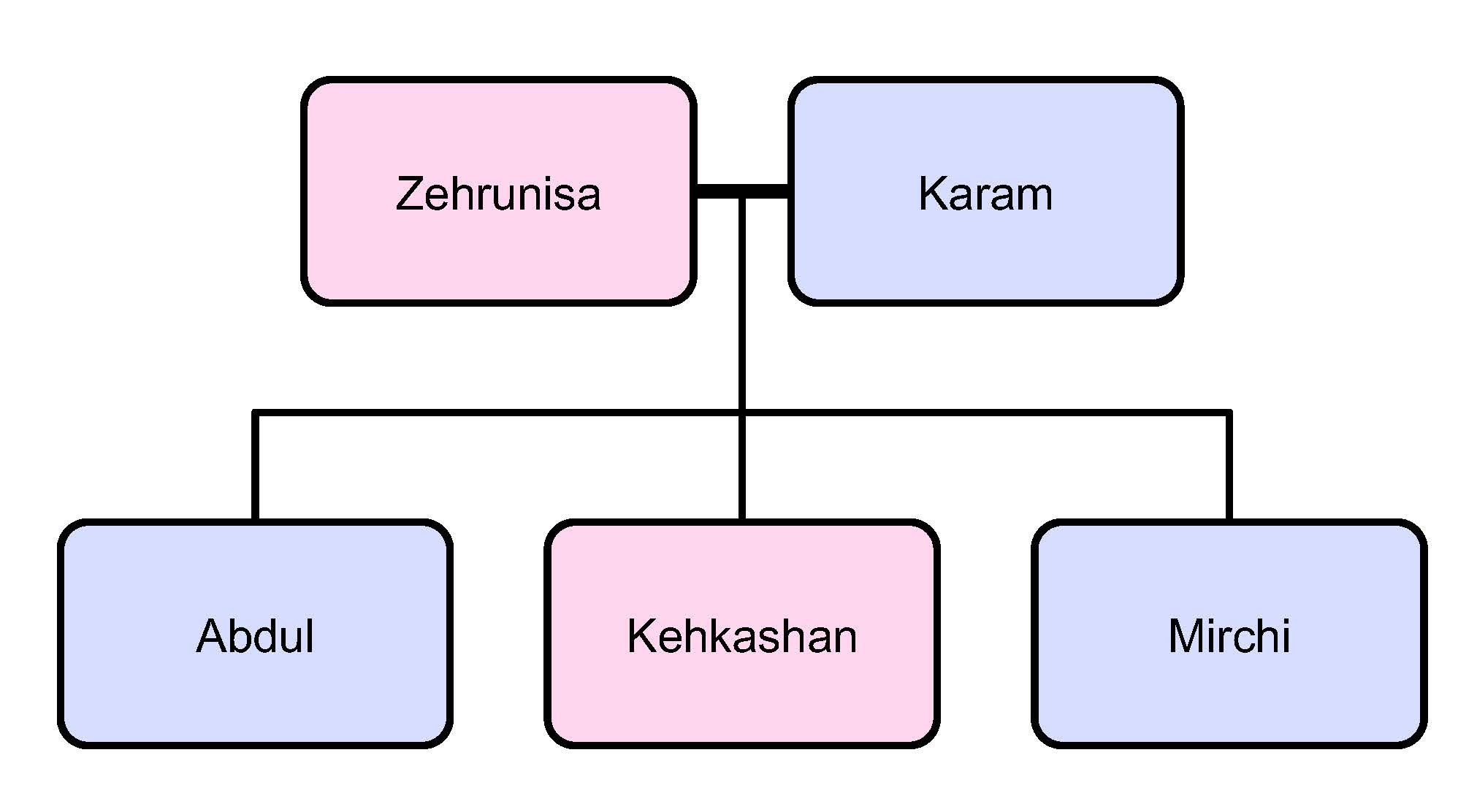

Abdul and the Husains

By the standards of the slum, the Husains are a well-to-do family: they earn up to eleven dollars a day with their garbage business.

Karam started it, but at present, he is an asthmatic and tuberculosis-stricken man too sick to go on working at a place where the air is so full of sand and gravel (coming from a nearby concrete plant).

Karam’s wife is Zehrunisa, a hard-working mother of three.

And these three are Abdul, a boy in his late teens and one of the main characters of the book, Mirchi, his younger brother who goes in the ninth grade, and Kehkashan, his sister.

Now, Abdul, a second-generation garbage picker, is the primary source of income for the Husain family. The dream of this family is something many people on the West take for granted: to legally own something of their own. (Remember: everybody is living illegally in the Annawadi slum on airport land.)

They have spent years—and Karam and Zehrunisa have paid this dearly with their health and wellbeing—earning just enough money to pay a deposit for a plot.

Hopefully, one day, they will be able to live in a decent house of their own.

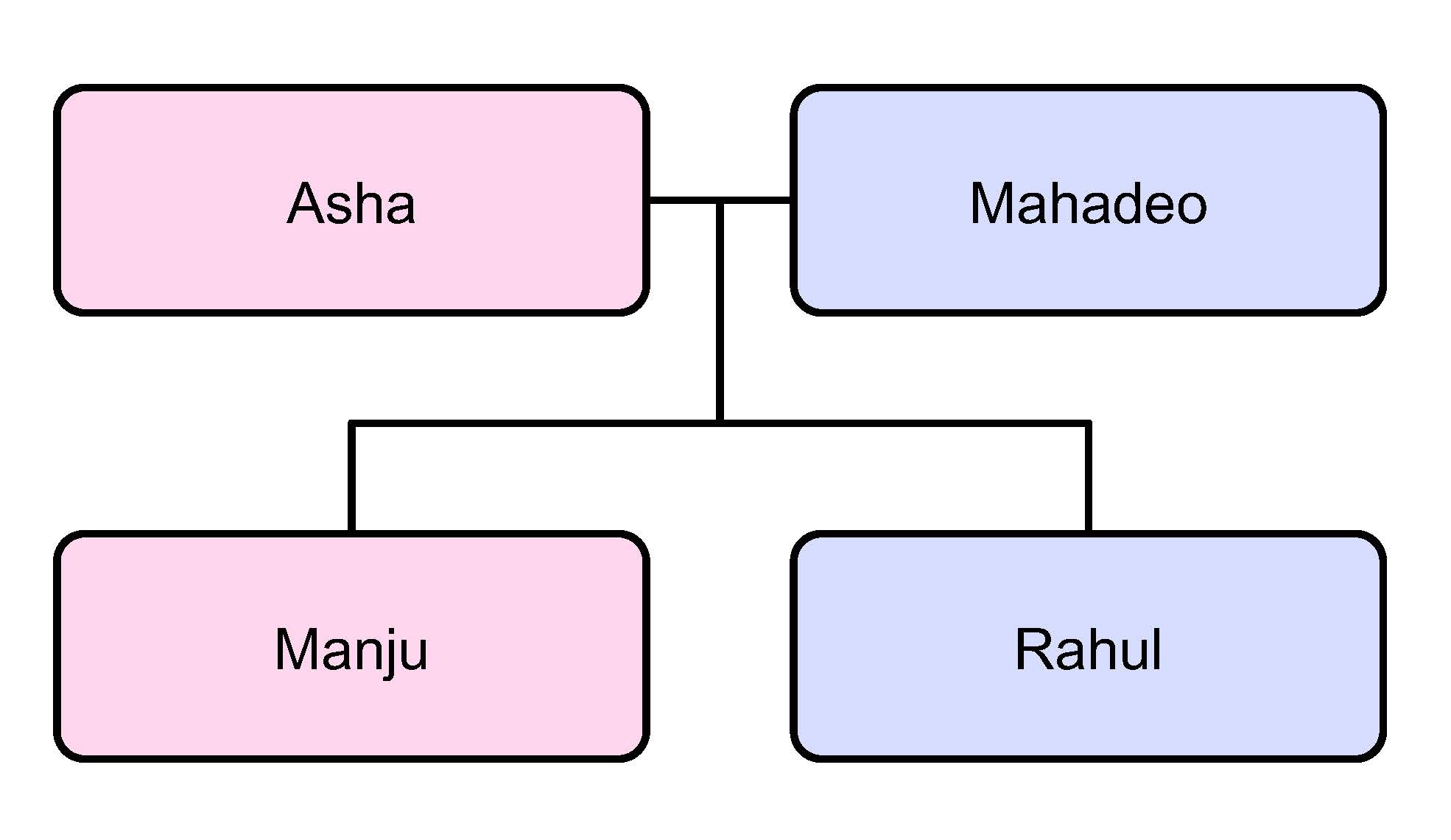

Asha and Manju Waghekar

Asha is the teacher supposedly running the let’s-call-it-school in the Annawadi slum.

Also, she is basically the first female slumlord, a “person chosen by local politicians and police officers to run the settlement according to the authorities’ interests.”

And the authorities’ interests are rarely the interests of the people living in the slum. So, Asha is basically a traitor.

But she doesn’t see herself as one.

In her mind, the Hobbesian “every man for himself” is not just an observation, but a suggestion on how one should live his/her life.

She has started at the bottom and has raised to the top through her own dealings. And unlike most of the families where the females exist merely in relation to their male counterparts, Asha runs everything in the Waghekar family, her husband Mahadeo being nothing more than a drunkard.

Wondering how Asha made it to the top?

The only way one can in the slum: mercilessness and lack of empathy, prostitution and corruption. A single example: Mr. Kamble, one of the Annawadi residents, desperately needs a new heart valve.

And since Asha is the only connection between the slum residents and the authorities—and even health officials—he goes to her and asks her for some help.

“A dying man,” she says after refusing his gradually increasing bribe several times, “should pay a lot to live.”

Even though they respect her spirit, Asha’s behavior is not exactly adored by her two children: Rahul and Manju.

Manju is Asha’s teenage daughter, a sweet girl with a desire to become the first female from Annawadi to graduate from college.

A noble thing to do, but make no mistakes: the schools in Annawadi are not even remotely similar to the schools you know.

A quick example: imagine learning a language without a dictionary!

Sunil and Sunita

Sunil and Sunita are a brother and a sister who started their lives in the orphanage across the street from the slum.

However, once Sunil reached the age of 11, he was kicked out of the school by Sister Paulette, who deemed him “too much to handle.” The only thing Sunil could do: to accustom himself to “scavenging work, to rats that emerged from the woodpile to bite him as he slept, and to a state of almost constant hunger.”

Sunil’s younger sister Sunita didn’t want to hear to remain at the orphanage in the absence of her brother, so she left it as well.

Now Sunil is not only not taken care of—his father too is an alcoholic—but he also has to take care of his sister.

To do that, he becomes a trash picker and earns his money by selling his garbage to Abdul.

However, he dreams of something much bigger, and sincerely believes that if he becomes a better trash-picker, he may one day be a wealthy person.

To his eyes, he would have been just that even now if he didn’t have such a dreadful childhood which severely affected his growth. Though 11-12, he looks as if 8-9, and the fact that even though older, he’s shorter than his sister, pains him deeply “on a masculine level.”

The Case of the One-Legged Fatima

Now, one day, while the Husains are renovating their house, they accidentally shake a brick wall which belongs to their neighbor, Fatima, a mentally unstable, one-legged woman.

Apart from some rubble falling into a pot of rice, there’s basically no damage; however, since Fatima—just like many other slumdogs—is jealous of the Husains’ wealth, she immediately blames them to have wrecked her house.

So, as is only natural in cases such as those, she asked a full compensation.

Expectedly, the Husains refuse to do this, and this sends Fatima in such a frenzy that she eventually sets herself on fire.

And since nobody cares about nobody in the slums, Fatima eventually dies from her injuries.

At the hospital, however, she mentions the Husains in relation to her death, and a corrupted government official named Poornima Paikrao, crafts a false statement in which the Husains are explicitly responsible for Fatima’s self-immolation.

Of course, the reason why Poornima is doing that is so that she can earn some money from the Husains to retract the statement. And that’s precisely how every member of the justice system and every inhabitant of the slum seems to think at this moment.

So, the Husains start paying bribes all around them—because, in the opposite case, they know that everybody is going to lie and turn their lives into living nightmares.

Not that this doesn’t happen to some extent: most of the Husains are jailed before the trial, so they can’t even earn their income.

To make things even worse, Abdul is kept there the longest.

Of course, in the end, the Husains lose both their plot and their deposit.

The Suicides of Meena and Sanjay

The worst thing is the destiny of the Husains is merely one of the many tragic fates in Annawadi.

Take, for example, Abdul’s friend Kalu. He is a homeless man suffering from tuberculosis; for a brief period of time, he also worked with Sunil.

One day, while Abdul is in jail, Kalu is violently murdered at the airport, something witnessed by many inhabitants of the slum.

However, the authorities couldn’t care less about the truth behind the murder: Kalu’s death, to them, can be basically translated as “one less slumdog to care for.”

So, the authorities attribute Kalu’s death to tuberculosis, something many of the people in the slum suffer from.

But not before faking an investigation.

They pick up Sanjay, a beautiful garbage picker, who has, in fact, witnessed the murder. Even though he has absolutely no connection to it, the police threaten him and beat him up.

Afraid both of the police and the actual murderers, one day, Sanjay drinks a bottle of rat poison and dies.

Meena, the first girl born in Annawadi and a friend of Manju, decides that suicide is a much more favorable outcome than living as well.

Why?

Because she is a teenage girl whose parents and brothers not only forbid her to go to school but also beat her up anytime her housework is deemed unsatisfactory.

Unlike Sanjay, she dies six days after eating some rat poison.

Now that’s painful.

Just too, too painful.

Key Lessons from “Behind the Beautiful Forevers”

1. When Dodging a Catastrophe Is Good Fortune

2. The Cancer of Corruption

3. Consider the Slums of Mumbai a Symbol

When Dodging a Catastrophe Is Good Fortune

Don’t get us wrong: dodging a catastrophe is always good fortune.

But, to some people, that’s the only good fortune they can hope for. In Annawadi, writes Boo, “fortunes derived not just from what people did, or how well they did it, but from the accidents and catastrophes they dodged. A decent life was the train that hadn’t hit you, the slumlord you hadn’t offended, the malaria you hadn’t caught.”

Some life, ha?

The Cancer of Corruption

Sometimes it feels like there’s nothing worse than corruption.

Absolutely nothing.

In the slums of Mumbai, corruption is what makes it almost impossible for even hardworking individuals to rise above poverty and actually get out of this hell worse than hell itself.

And the worst part about corruption is that spreads fairly quickly.

Because when the only way you can survive is through corruption, then you don’t feel it as if it is corruption in the first place, do you?

Consider the Slums of Mumbai a Symbol

Junot Diaz describes the sentences which end Behind the Beautiful Forevers as lines “that just about freeze your heart.”

Part of their message is in the title of this key lesson. But we believe you should read them in their entirety to understand why Diaz calls them chilling.

What was unfolding in Mumbai was unfolding elsewhere, too. In the age of global market capitalism, hopes and grievances were narrowly conceived, which blunted a sense of common predicament. Poor people didn’t unite; they competed ferociously amongst themselves for gains as slender as they were provisional. And this undercity strife created only the faintest ripple in the fabric of the society at large. The gates of the rich, occasionally rattled, remained unbreached. The politicians held forth on the middle class. The poor took down one another, and the world’s great, unequal cities soldiered on in relative peace.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Behind the Beautiful Forevers Quotes”

Much of what was said did not matter, and that much of what mattered could not be said. Share on X I tell Allah I love Him immensely, immensely. But I tell Him I cannot be better, because of how the world is. Share on X In Mumbai's dirty water, he wanted to be ice. He wanted to have ideals. Share on X Your little boat goes west and you congratulate yourself, ‘What a navigator I am!’ And then the wind blows you east. Share on X Being terrorized by living people seemed to have diminished his fear of the dead. Share on XOur Critical Review

When asked a few years ago by The Sunday Book Review what’s “the last great book” he has read, Junot Diaz answered without thinking: Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers.

“A book of extraordinary intelligence, humanity and (formalistic) cunning,” he added. “Boo’s four years reporting on a single Mumbai slum, following a small group of garbage recyclers, have produced something beyond groundbreaking.”

Why would he say such a thing?

Because, in his opinion, Boo “humanizes with all the force of literature the impossible lives of the people at bottom of our pharaonic global order, and details with a journalist’s unsparing exactitude the absolute suffering that undergirds India’s economic boom. The language is extraordinary, the portraits indelible…”

So, there you have it: Behind the Beautiful Forevers has the best of both worlds.

Or, to paraphrase a New York review, Boo’s report reads like Watergate, and it is written like Great Expectations.

No one can ask something more from a book.