Summary Thomas Hobbes

11 min read ⌚

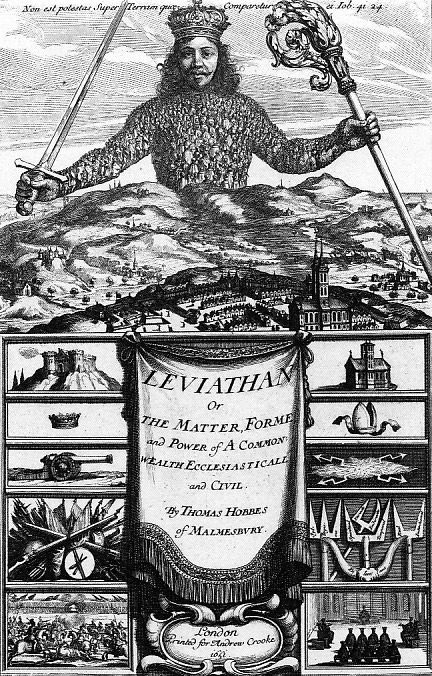

The Matter, Form and Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiastical and Civil

The Matter, Form and Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiastical and Civil

Now, that has to be one of the greatest covers of all time!

A monstrous creature with the head of a man and the body of, well, three hundred smaller men, ominously waving a sword and a staff over the world.

Above him, in Latin, a quote taken out of the Book of Job: “There is no power on earth to be compared to him.”

And below, the title:

Who Should Read “Leviathan Summary Thomas Hobbes”? And Why?

Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes is perhaps the earliest and inarguably one of the two most influential texts which have attempted to sketch the ideal social contract – in addition to pinning down its origin and its significance (the other, of course, being Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Contract).

As such, it is one of the cornerstones of modern political philosophy, and one of the first books you should read if you are interested in that field.

Then move on to Rousseau. Then contrast and compare.

There: you’re halfway through understanding the whole field.

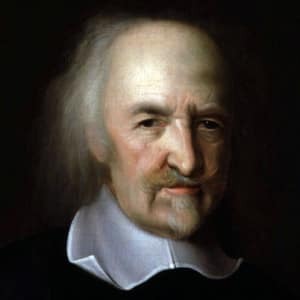

About Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes was a 17th-century English philosopher and political thinker, one of the foremost figures of the European Enlightenment.

Thomas Hobbes was a 17th-century English philosopher and political thinker, one of the foremost figures of the European Enlightenment.

Best known for his 1651 book, Leviathan, Hobbes was a polymath who made significant contributions in more than one field of inquiry, ranging from history and philosophy to geometry and physics.

He is widely considered one of the founders of modern political philosophy, and, paradoxically (since he championed the absolutism of the sovereign), a precursor of classical liberalism.

“Leviathan Summary”

Written in 1651, Leviathan is titled after a sea monster mentioned in the Bible, most notably in the Book of Job. There’s a lengthy description there – if you want to, you can read it here (it starts in the previous chapter, verse 25) – but, let’s just say that the Leviathan is not something you’d want to mess with.

Looking at the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’ book, you probably already know what we’re talking about.

Surprise, surprise –

You don’t.

Because even though, at first sight, this image of the Leviathan calls to mind a dystopian dictatorship, it actually represents Hobbes’ vision of an ideal social contract, aka the perfect civil society.

Strangely enough, Hobbes does have a point why you need a sea monster and not a butterfly to serve as a metaphor for a utopian society.

Most of it is presented in the first book of Leviathan, with the other three further analyzing the political implications of the philosophical conclusions reached at the beginning.

So, let’s see what’s Hobbes’s deal.

Part I: Of Man

Mechanical Interpretations

The first part of Leviathan is the most important one—it is the one upon which all the others are founded.

In other words, if there’s something wrong with it, then you’ll undoubtedly find quite a lot of flaws in the other three parts as well.

Which is why everybody spends about a hundred times more time analyzing this first part in comparison to the time spent on the other three parts.

And its essence?

Well, basically, that all of those sentimental, spiritual, otherworldly explanations of what we are and how we live are just a bunch of nonsense!

In other words, every single feeling and concept can be explained mechanically and materialistically, in terms of the movements of our bodies and minds toward or fromward objects, which, in turn, can be absent or present.

Our mind is moving toward or backward in terms of opinions; our body is moving in terms of appetites/desires (when toward an object) and aversions (when fromward an object).

Let’s make that clearer for you!

Say you have an appetite/desire for something, coupled with an opinion that you can get that something; then you’re experiencing hope. In this case, both your body and your mind are moving toward that thing.

However, if you just have an appetite for a thing, but you don’t believe that you can ever obtain it – then, that’s despair; your mind is moving backward now, even though your body is still prompting you to go toward that thing.

Fear is when both your mind and your body are averted, “with opinion of hurt from the object;” courage is “the same, with hope of avoiding that hurt by resistance;” anger is sudden courage, etc. etc.

Good vs. Evil

As you can see, similarly to Aristotle, Hobbes thinks of some feelings as much more complex than the others.

But just like molecules – no matter how complex – can be ultimately broken down into one of no more than 118 atoms, feelings and concepts can be too, and into no more than a few “bodily” movements and “mindedly” opinions.

Now, you’d expect that the most complex emotions and states – such as Good and Evil – should be the most complex arrangements of simple feelings and concepts, right?

Wrong!

You know why?

Because they are the simplest.

And this is both the catch and the most important inference from Hobbes’ mechanical analysis of the human species!

In essence, he says in an anachronistic language we’ll spare you the trouble from interpreting for now, there are no such things as Good and Evil.

We say that something is good if that something aligns with the appetites and desires of our body and our mind; if, however, it doesn’t, we call that thing bad, “vile, and inconsiderable.”

The words good and evil, Hobbes goes one, are always used with relation to the person who uses them.

The point?

There is nothing simply and absolutely good or bad in nature; the goodness or badness of a thing – when there is not such a thing as a commonwealth (see part II) – is taken from the person of the man who judges it or represents it.

The bottom line?

Whatever is good for one person, is bad for another one; and vice versa.

Summum Bonum vs. Summum Malum

And therein lies the rub!

Hey, look – we inadvertently quoted Hamlet, a play written half a century before Hobbes’ Leviathan!

Are we trying to make some point?

Of course we are (aka it wasn’t at all inadvertently)!

We wanted to remind you, as a side note, that Shakespeare managed to sum Hobbes up in a single sentence from the second scene of Act II of Hamlet: “there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

However, there’s a reason why Hobbes had to write about a hundred pages to explain that sentence.

It’s because, at his time, everybody believed the opposite.

Namely, that there’s something, deep within us, which is divine and which helps us align our actions with the Highest Good, or, in Latin, the summum bonum.

This Idea of the Highest Good originates in Plato – remember, the essentialist Plato? – and is a Form which exists irrespective of us and which is the ultimate object of our striving and knowledge; it is from It that things on earth which are good gain their value and their usefulness.

So, we just need to discover It, and we’ll be able to understand everything that is good why it is good and everything that is bad why it is not good.

Think of it as the finish line of a race you’re running; once you see it, you know in which direction you should run and when to stop running.

Yeah, right – said Hobbes!

Everybody knows what’s good – to him.

And good luck Plato if you want to create a society based on summum bonum: there could be no such thing because everyone’s desires are different!

Fortunately, everyone’s aversions seem to converge at one point, the summum malum, the Greatest Evil.

Namely: violent death.

The Natural State

So, let’s turn this discussion on its head – advised Hobbes!

Instead of trying to do the impossible – i.e., create a society which will satisfy the desires of all of its members – let’s try to do something much more obtainable – create a society which will eliminate the aversions of its inhabitants.

Summum bonum – butterflies and zebras, and moonbeams and fairytales – is a myth; summum malum – the fear of being hit on the head with an ax or a sledgehammer – is much too real.

And it must have been – since the very beginning of times!

You see, in the absence of a community – that is, man’s natural state – it seems to have been every man for himself. And that, coupled with a lack of resources, must have resulted in a war of all against all, the only conceivable state of men without civil society.

Because when there are no such things as a common good and a common bad, all men have “equal right unto all things:”

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor the use of commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

The Natural Laws

Because this is something nobody wants – because it is something which could destroy everybody – some laws must have evolved spontaneously.

Hobbes calls these natural laws (leges naturales) and defines them as precepts, or general rules, “found out by reason, by which a man is forbidden to do that which is destructive of his life, or take away the means of preserving the same; and to omit that by which he thinks it may be best preserved.”

Hobbes comes up with 19 such laws, the first two of which are by far the most important.

The first and fundamental law of nature and reason is this: “that every man, ought to endeavor peace, as far as he has hope of obtaining it; and when he cannot obtain it, that he may seek, and use, all helps, and advantages of war.”

It sounds a bit Kantian, doesn’t it?

If I can war to obtain the things I like, then everyone can do that too, and this means that I should fear for my life on a daily basis. So, it’s better for me not to wage war in cases where I can obtain peace; and when peace is out of the question, only then I should resort to warring.

Neither sentimental nor humane, but a giant leap from the natural state!

Now, from this “fundamental law of nature” follows the second one, according to which a man should be “contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himself.”

It’s both liberalism at its best, and even more Kantian once you think about it.

In fact, Hobbes sums up this law thus: “Whatsoever you require that others should do to you, that do ye to them.”

So, the Golden Rule yet again!

Parts II-IV

Part II: Of Common-Wealth

So, basically, the essence of these two natural laws is this: instead of acting as packs of wolves, let’s act as organs of a single body.

This single body – the one on the cover – is the Commonwealth, whose purpose Hobbes describes thus:

The final cause, end, or design of men (who naturally love liberty, and dominion over others) in the introduction of that restraint upon themselves, in which we see them live in Commonwealths, is the foresight of their own preservation, and of a more contented life thereby; that is to say, of getting themselves out from that miserable condition of war which is necessarily consequent, as hath been shown, to the natural passions of men when there is no visible power to keep them in awe, and tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants.

Then Hobbes goes on to describe the twelve principal rights of the sovereign, the three types of government (monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy; monarchy is, yet again, the best), the succession and the taxation rules.

Not that exciting or original; but also kind of interesting.

Part III: Of a Christian Common-wealth

Which you can’t say about the third part of Leviathan, in which Hobbes tries to see how compatible Christianity is with his philosophical ideas.

Considering the fact that he was oftentimes called an atheist – and this was at a time when that was worse than being called, well, anything – it seems only necessary that Hobbes devoted so much of his time and energy to explaining something which, nowadays, would have been unnecessary.

However, behind all the biblical scholarship, the gist of this third part is rather simple: religious power must be subordinate to civil power.

Why?

Because, just like Good and Evil, revelations are just too subjective and too untestable!

For example, I can casually say that an angel gave me a golden book with, I don’t know, seventeen new commandments which go against the civil laws of a country; and you wouldn’t be able to disprove me.

And that, logically, shouldn’t be allowed if you want a just civil society.

Part IV: Of the Kingdom of Darkness

As you can infer from the title, the fourth part of Leviathan is also interested in some biblical ideas. More specifically, in how to guard the Commonwealth against liars and deceivers.

Hobbes lists four types of religious deceivers one should be especially wary about:

#1. Misinterpretators; these are people who cite and quote the Holy Book to prove that there are such things as angels and demons; yes, Hobbes is talking about the priests.

#2. Demonologists; these are people who not only claim that there are angels and demons, but they also claim to know how to deal with them; yes, Hobbes is explicitly talking about the Catholic Church and the Pope;

#3. Crusaders against the Truth; these are people who use the Scripture to punish other people for their opinions; he specifically mentions his friend Galileo’s punishment asking “what reason is there for it? Is it because such opinions are contrary to true Religion? That cannot be, if they be true;” great observation, Thomas;

#4. Privileged truthers; these are those who, for some reason, others believe that have privilege over the truth; the point being: scientists and philosophers have as much right to truth as priests and the Pope himself.

Key Lessons from “Summary Thomas Hobbes”

1. A War of All Against All

2. The Natural Laws

3. The Commonwealth

A War of All Against All

Hobbes’ Leviathan is perhaps most famous for its idea that the natural state of man was one of war of all against all.

Why?

Because, in Hobbes’ opinion, good and evil are subjective, and when there are no communities, everybody has equal right upon everything.

When that is the case – nobody is safe.

The Natural Laws

And it is precisely because nobody is safe in a bellum omnium contra omnes state of affairs that, after some time, people had to come up, intuitively, with these two laws.

It isn’t that they devised them or put them down on paper or something – it’s just that they realized that, if they want to work for themselves, they have to follow them.

The first law is that peace is better than war when the former is an option; and the second, that one should be content with that freedom which doesn’t affect the freedom of other people, because that’s the freest one can be without risking a conflict.

The Commonwealth

Most of Leviathan is actually a description – as the book’s subtitle explicitly states – of the matter, form and power of the commonwealth,

It is a community ruled by a sovereign, which helps people get themselves out from “that miserable condition of war which is necessarily consequent… to the natural passions of men when there is no visible power to keep them in awe, and tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants.”

The best civil commonwealth is a monarchy, separated and superior to the ecclesiastical, i.e., religious part of the government.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Summary Thomas Hobbes Quotes”

Curiosity is the lust of the mind. Share on X Hell is truth seen too late. Share on X The condition of man... is a condition of war of everyone against everyone. Share on X Leisure is the mother of philosophy. Share on X Force and fraud are in war the two cardinal virtues. Share on XOur Critical Review

Leviathan is one of the first-order classics of political philosophy.

However, do yourself a favor and don’t bother that much with parts II to IV – fortunately, we’re now past them.

Part I, however, is so thought-provoking it will probably be discussed for as long as we exist; or, at least, find a scientific proof that it is or isn’t right.