Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus Summary

7 min read ⌚

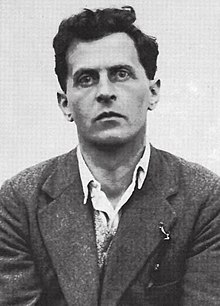

Ludwig Wittgenstein is widely considered to have been one of the greatest – if not the greatest –philosopher of the 20th century.

Ludwig Wittgenstein is widely considered to have been one of the greatest – if not the greatest –philosopher of the 20th century.

At about 80 pages, “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus” is the only book he published during his lifetime.

And for some time – if you had asked Wittgenstein and his followers – it was the only philosophical work that was worth your time and attention.

Join us and find out what the fuss is all about.

Who Should Read “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus”? And Why?

Since it is a landmark work in the history of philosophy, everyone who is even remotely interested in philosophy and the history and evolution of thought.

However, considering the fact that it is notoriously complicated, not everyone will be able to do so in the absence of scholarly annotations and copious notes.

So, whatever you do, don’t let the size of “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus” fool you: it will probably take you to read it as much as time as it would take you to read Dr. Johnson’s “Dictionary of the English Language.”

And, sorry to say, but unless you are really interested in philosophy and language, of the two, the latter will probably be the more interesting one.

About Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein was an Austrian-British philosopher, deemed by Bertrand Russell “the most perfect example… of genius as traditionally conceived; passionate, profound, intense, and dominating.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein was an Austrian-British philosopher, deemed by Bertrand Russell “the most perfect example… of genius as traditionally conceived; passionate, profound, intense, and dominating.”

Born into a wildly wealthy family in Vienna, Wittgenstein first studied engineering in Berlin, and it is with the goal of furthering his education in this area that he went to England, more precisely Manchester.

However, he soon developed a keen interest in mathematics and logic and on 18 October 1911, he arrived announced before Bertrand Russell at Cambridge, with an intention to become the greatest philosopher in history.

Two years later, he inherited a large fortune from his father, but he gave most of it away to artists and poets, and especially to his already rich brothers and sisters.

After three of his brothers had committed suicides – and thinking that he had solved all philosophical problems with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (published in 1921) – the mentally and emotionally spent Ludwig gave up philosophy altogether and spent the next few years working as an elementary school teacher, gardener, and an architect.

In 1929 he went back to Cambridge where he became a professor in 1939. He died of cancer twelve years later.

“Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus PDF Summary”

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus” is one of the strangest and most forbidding texts in the history of philosophy – and, yes, that comes in a field occupied by the likes of Kant, Hegel, and Heidegger.

At least these three left behind them Bible-sized volumes and volumes of works!

Wittgenstein’s magnum opus is barely 80 pages and 526 propositions long. And in young Wittgenstein’s humble opinion, it managed to resolve all philosophical problems once and for all.

Quite a strange thing to think if you take into consideration the fact that, by his own admission – stated in the preface to the “Tractatus”:

The whole sense of the book might be summed up the following words: what can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.

If you had troubles understanding that sentence, then don’t bother reading anything other than this summary.

Really!

Because – we kid you not! – that sentence is probably the least complicated in this book, plagued throughout by such pearls of wisdom as “The world is everything that is the case” and “A proposition is a truth-function of elementary propositions,” by the way, two of its seven main propositions.

However, we did include this book in our list of 15 most important nonfiction works in history, so, all joking aside, there must be some reason why we believe it to be as important as, say, Darwin’s “The Origin of Species.”

And, most certainly, there is!

You see, Wittgenstein’s aim was, through this book, “to set a limit to thought, or rather… to the expression of thoughts.”

In other words, his goal was to find out what we can know and what we can’t know – and if there are some things we will never know no matter how much we think about them (rendering the thinking about them futile and a waste of time).

In trying to solve that, he developed a radical philosophy of both language and thought – one that may even explain why you had that quarrel with your partner today over that completely unimportant and trivial matter.

And as Wittgenstein himself tried to point out over and over again, this philosophy is actually fairly simple!

He first had an inkling of it when he read in a newspaper about a court case in Paris, during which the judge suggested that the crime scene be reconstructed with model cars and pedestrians.

Why?

Because language wasn’t clear enough; if it had been, nobody would have needed a reconstruction of the scene since everybody would have had the same picture of it.

And that’s the gist of Wittgenstein’s famous picture theory of language.

Namely, if the world is made up of certain facts (i.e., things which are the way that they are) and language is made of certain propositions which we utter in relation to these facts, then everything that we say must be either true (if it presents the facts truthfully) or, otherwise, false.

In a nutshell, every single proposition is basically a picture of a fact the same way a map is a picture of the world; and the same way a map of Paris can present the real Paris the right and the wrong way, a proposition can be either true or false.

Now, a map testable: if you follow a route and you get to the place it suggests you will, it is the correct map; if you don’t, it is a poor picture of reality.

Well, Wittgenstein says that even though mapmakers don’t have the luxury of being wrong (you won’t buy the map which pictures reality wrongly), philosophers seem to have been privileged to say everything they like with impunity!

In Wittgenstein’s belief, this is the root of all the world’s problems: every single proposition which doesn’t picture facts, he claims, is meaningless.

Consider, for example, this sentence: “Love is grand.”

Even though fairly logical and comprehensible, in Wittgenstein’s opinion, this sentence is meaningless since it’s not a picture of the world, for the very simple reason that there’s no definition of what love is and, consequently, this can be a lie as much as it can be the truth.

But does that mean that Love doesn’t exist?

No – and this is where Wittgenstein becomes even more interesting: “There is indeed the inexpressible,” he notes at one place (6.522). “This shows itself; it is the mystical.

In other words, there are things which are grand and mystical; the problem is they cannot be put into language exactly because of that:

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world. (5.26)

Key Lessons from “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus”

1. Propositions Are Picture of Facts

2. What We Talk About When We Talk About Love… or Many Different Things

3. Silence Is Golden

Propositions Are Picture of Facts

Wittgenstein’s picture theory of language is a fairly simple one, based on two straightforward propositions and the relation between them:

#1. Language is made up of propositions

#2. The world is made up of facts

#1-2. Propositions are pictures of facts and can be either true or false; if neither – they are meaningless.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love… or Many Different Things

Some propositions – such as “the cat sat on the mat” – are obviously related to the world: if the cat did sit on the mat, then this proposition is true, and if it didn’t, then it is false.

But what about a proposition such as “Thou shalt not commit adultery”?

Well, in the opinion of Wittgenstein, this proposition is a meaningless one, since it doesn’t picture anything that is a fact outside of language.

Ethics,” notes Wittgenstein, “is transcendental,” i.e., “It is clear that ethics cannot be expressed. (6.421-6.422)

Silence Is Golden

And, now, for the twist: the propositions of the “Tractatus” themselves are not pictures of the world in the strict sense we analyzed above.

Then, how are they different from the other meaningless expressions?

In this, and this way only:

My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it.) (6.54)

Which leads to Wittgenstein’s most famous dictum:

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent. (7)

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app, for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus Quotes”

Language disguises thought. Share on X

Ethics and aesthetics are one. Share on X

For an answer which cannot be expressed the question too cannot be expressed. The riddle does not exist. If a question can be put at all, then it can also be answered. Share on X

We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all. Share on X

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent. Share on X

Our Critical Review

Retrospectively, Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus” may have caused just as many problems as it has actually solved.

But, even so, it’s a landmark work.

And you should give it a try!