A Doll’s House Summary

10 min read ⌚

There aren’t many plays more performed than Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House.” In fact, quite probably, if there are, they are either by Shakespeare or Chekhov.

There aren’t many plays more performed than Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House.” In fact, quite probably, if there are, they are either by Shakespeare or Chekhov.

Unsurprisingly, since “A Doll’s House” is widely considered one of the greatest plays ever written.

And it treats problems which are still problems in most of the world.

Who Should Read “A Doll’s House”? And Why?

When it was first performed a few days before the Christmas of 1879 in Copenhagen, “A Doll’s House” caused an uproar few plays have managed to in the entire history of literature.

The play was so divisive, in fact, that many party invitations of the 1900s explicitly forbade guests to start a conversation about it.

Which tells us at least three other important things:

First of all, Norway parties would have been rather dull for normal people such as you and me; after all, if you remember, in “Hedda Gabler” a character goes to a party with the intention of reading out loud the manuscript of a history book! That’s not what we’d call a party, Norway!

Secondly, whatever happens in Norway, happens in the rest of the developed world a few decades later. No wonder Norway is usually the happiest country in the world – they discussed on 1900s parties things Americans discussed in the 1960s.

And thirdly, that you must read this play. If it was so important to be banned, and so influential to be instrumental in giving women more rights – then it’s certainly not something you’d like to miss.

After all, it’s Ibsen.

This is probably his most famous play.

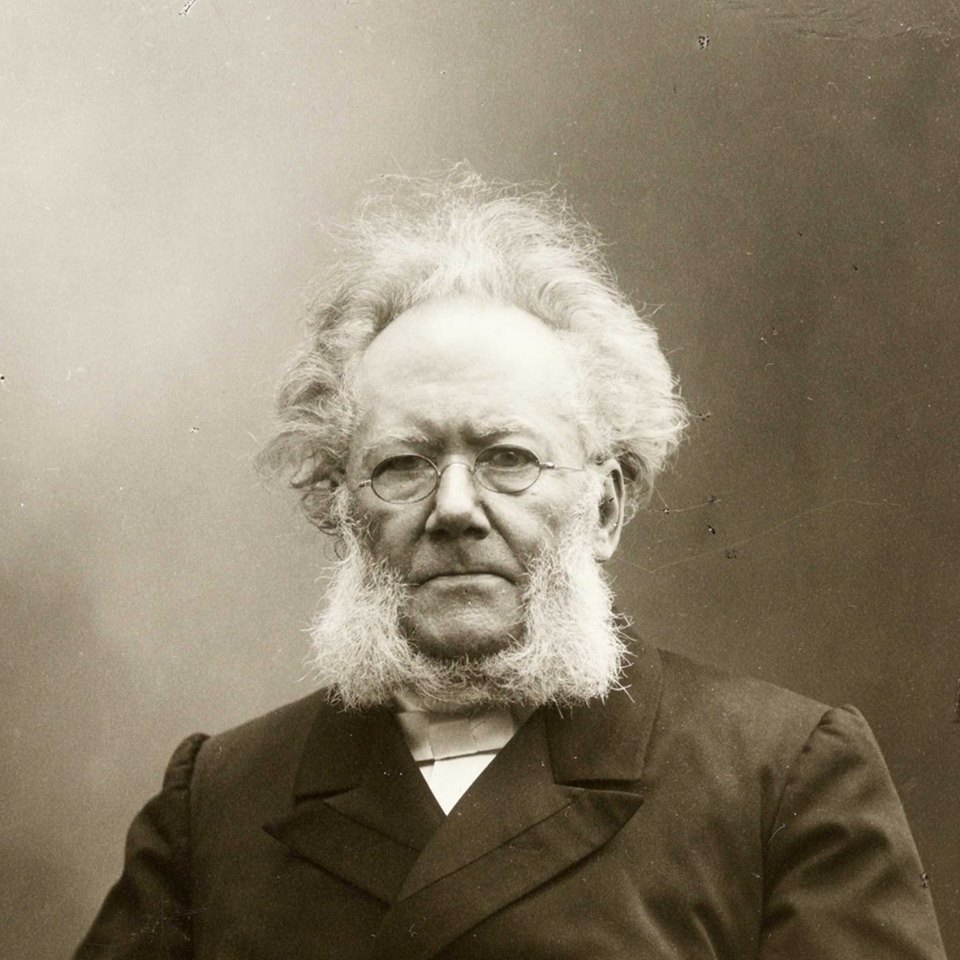

Henrik Ibsen Biography

Henrik Ibsen was a Norwegian playwright, considered “the father of modern drama” and possibly the most influential dramatist since William Shakespeare. In addition, he is the second most frequently performed playwright after him to this day.

was a Norwegian playwright, considered “the father of modern drama” and possibly the most influential dramatist since William Shakespeare. In addition, he is the second most frequently performed playwright after him to this day.

He was born into a merchant family in Skien, but he spent most of his life outside Norway, mainly in Rome and Munich. He wrote most of his plays in Danish and was predominantly interested in stories capable of changing the world.

Many of them did: “A Doll’s House,” “Hedda Gabler,” “An Enemy of the People,” (adapted in the U.S. by none other than Arthur Miller in the 1950s) “Ghosts,” “The Wild Duck,” and “Pillars of Society” probably most significantly.

Other Ibsen plays include: “Peer Gynt,” “When We Dead Awaken,” “Emperor and Galilean,” “Rosmersholm,” “The Lady from the Sea,” “The Master Builder,” and “John Gabriel Borkman.”

Plot

Act One

It’s Christmas Eve and a porter delivers a Christmas tree to the house of Nora and Torvald Helmer. Already feels like a beginning more suited for a Hallmark movie than a serious Realist play.

True to first impressions, the life of the Helmers looks nothing less than idealistic. The spouses even have pet names for each other – and what is love if not the opportunity to call someone by a name you’d only use for a child.

(Following the grand male tradition of affectionally equating women with animals, Torvald refers to Nora as his “little skylark.” It’s ominous – but you don’t know this yet.)

Nora and Torvald are in celebratory mode: Torvald has been promoted, so, their future looks even more beautiful than their all-but-perfect present.

Nothing suggests that things will change even when Mrs. Kristine Linde and Dr. Rank arrive, the former an old school friend of Nora – now widowed – and the latter a rich and terminally ill family friend of the Helmers, secretly in love with Nora.

Kristine is unhappy and looks for a job; Nora says that she will help her, fully convinced that, now that he is a Bank Manager, Torvald will be able to give her one. And he does do exactly that.

During Nora and Kristine’s conversation, we learn that Nora and Torvald had some problems with money too.

Namely, Torvald was not that long ago sick and Nora had to resort to borrowing some money to finance a trip to Italy which was the only way Torvald could have gotten better. Now she has paid off the debt, secretly working and saving money any way she could.

And the man she borrowed money from?

Mr. Nils Krogstad, an employee at Torvald’s bank and, to use Dr. Rank’s words for him, a “morally diseased” person. He is also a former lover of Kristine and the next person who enters the Helmer’s house.

And the reason for that?

Well, Torvald wants to have a word with him.

Which is a usual euphemism bosses use when they want to fire someone.

And, finally, the problem: Krogstad threatens Nora that if she doesn’t keep him the job, he will tell everything about her borrowing money from him.

Well, what? What’s wrong with borrowing money from someone if you return them down to the last penny?

Moreover, Nora didn’t exactly use it to buy herself a couple of dresses and hire a gigolo!

No – she used it all to help her husband get better!

So, what’s the problem?

Well, you’re forgetting that it’s the 19th century and women are not allowed to borrow money. (Now you can understand Virginia Woolf better: for most of human history, women were basically slaves.)

So, how did Nora do it?

By forging her father’s signature.

See the problem now?

Act Two

It’s Boxing Day and Nora doesn’t know what to do with herself.

Mrs. Linde arrives to help her sew her Italian fisher girl costume intended for a fancy party that Nora is supposed to go to the next evening. Kristine notices Nora’s anxiety and asks to learn something more about it.

However, Nora doesn’t want to tell her.

Instead, the moment Torvald enters, she starts begging him to keep Krogstad. The more she does that, the less Torvald wants to.

Few seconds later, he decides to fire Krogstad immediately.

Nice going, Nora – it just got from bad to worse.

Now, Krogstad comes and, after a brief discussion with Nora, we learn that not only he doesn’t want to be fired, but he wants to one day be able to run the bank.

Seeing that Nora is both uninterested and incapable of helping him more, on his way out, Krogstad leaves a letter explaining Nora’s transgression in Torvald’s letterbox.

The clock just started ticking faster.

Mrs. Linde returns and Nora has nothing to hide anymore from her. She explains everything and Kristine offers her help: as a former lover of Krogstad, maybe she will be able to talk Krogstad out of his intentions.

However, Krogstad is not at home and Mrs. Linde could do nothing more but leave him a note.

Nora, thinking about what the now all but inevitable revelation of the crime may do to her husband’s reputation, contemplates committing suicide.

And she declares that maybe she has only 31 hours left to live.

It’s the final countdown.

Act Three

December 27, the house of the Hellers.

Krogstad arrives there to meet Mrs. Linde, while the Hellers are at the ball.

Mrs. Linde explains to him that she loved him deeply, but that she married a richer husband since that was the only way she could support a family. Unfortunately, unlike Krogstad, she didn’t have one.

On the other hand, Krogstad, widowed himself, has children, and Mrs. Linde suggests a Solomonic solution: now that their spouses have both died, they marry each other.

That way, Krogstad gets a mother for his children and an employed wife, and Kristine gets a husband, and a fulfillment of her wish to be a mother.

Krogstad agrees and even offers to ask for his letter to Torvald back. Mrs. Linde changes his mind: it’s time that the truth comes out, she says.

Krogstad and Mrs. Linde leave, and Nora and Torvald return.

Torvald showers Nora with praises and even utters something that makes Nora hope for a wonderful thing, a miracle: “Do you know, Nora, I have often wished that you might be threatened by some great danger, so that I might risk my life’s blood, and everything, for your sake.”

Dr. Rank comes in and, after drunkenly complimenting the party and the wine, he puts two visiting cards in Torvald’s letterbox indicating that he’s about to die.

Knowing what Torvald will find there besides Dr. Rank’s cards, Nora sneaks out into the hall, all but prepared to commit suicide.

A Doll’s House Epilogue

Torvald stops her.

But only to inform her of what he has found out and to start shouting at her as he has never before:

It is so incredible that I can’t take it in. But we must come to some understanding. Take off that shawl. Take it off, I tell you. I must try and appease him some way or another. The matter must be hushed up at any cost. And as for you and me, it must appear as if everything between us were just as before–but naturally only in the eyes of the world.

You will still remain in my house, that is a matter of course. But I shall not allow you to bring up the children; I dare not trust them to you. To think that I should be obliged to say so to one whom I have loved so dearly, and whom I still–. No, that is all over. From this moment happiness is not the question; all that concerns us is to save the remains, the fragments, the appearance—

Yup – Torvald’s little skylark is suddenly unfit to raise his children.

And his reputation is much more important than her happiness.

And then a miracle happens: the maid brings a note from Krogstad. It says that a happy occurrence in his life has made him change his mind. He even encloses the bond.

Torvald is more than happy.

He hugs Nora, telling her that he forgives her.

Forgives her?

Oh, no Torvald, it doesn’t work that way.

Or at least it won’t – from now on.

Nora takes off her dress and, clad in everyday clothes, after taking a look at her watch, utters one of the most famous sentences in all of the world’s drama:

Sit down here, Torvald. You and I have much to say to one another.

And when she says that she and him have a lot to talk about, she means that women and men have a lot to say to each other.

But, for once, it’s women’s time to talk.

Nora talks, saying that she is disappointed in Torvald and that she expected a miracle. Revealing that she would have sacrificed everything (including her own life) for him. And telling him that she will now leave, alone, which means without their three children as well.

What follows is a discussion that resonates even a century later:

HELMER: It’s shocking. This is how you would neglect your most sacred duties.

NORA: What do you consider my most sacred duties?

HELMER: Do I need to tell you that? Are they not your duties to your husband and your children?

NORA: I have other duties just as sacred.

HELMER: That you have not. What duties could those be?

NORA: Duties to myself.

HELMER: Before all else, you are a wife and a mother.

NORA: I don’t believe that any longer. I believe that before all else I am a reasonable human being, just as you are–or, at all events, that I must try and become one. I know quite well, Torvald, that most people would think you right, and that views of that kind are to be found in books; but I can no longer content myself with what most people say, or with what is found in books. I must think over things for myself and get to understand them.

This ending was so shocking that actresses refused to play it out, claiming that no woman would ever leave her children.

But, Nora does.

The last thing Torvald – left alone and in despair – hears is the slamming of a door, which, as critics have pointed out, “reverberated across the roof of the world,” signifying “the end of a chapter of human history.”

In contemplating Henrik Ibsen’s enduring masterpiece, “A Doll’s House,” one cannot overlook its profound impact on societal norms and the portrayal of gender dynamics.

Nora’s journey from a seemingly content wife to a woman empowered to assert her own agency resonates with audiences across generations.

As we witness her pivotal decision to leave behind societal expectations, including her role as a mother, in pursuit of self-discovery, Ibsen invites us to reevaluate the constraints placed upon women in the 19th century and, by extension, in contemporary society.

Nora’s departure, marked by the resounding slam of the door, serves as a poignant reminder of the ongoing struggle for equality and individual autonomy.

In a world where women’s voices continue to strive for recognition, “A Doll’s House” remains a timeless beacon of courage and defiance against oppressive norms.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app, for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

A Doll’s House Summary Quotes

NORA: You have never loved me. You have only thought it pleasant to be in love with me. Share on X TORVALD: Do you know, Nora, I have often wished that you might be threatened by some great danger, so that I might risk my life's blood, and everything, for your sake. Share on X TORVALD: From this moment happiness is not the question; all that concerns us is to save the remains, the fragments, the appearance. Share on X TORVALD: I would gladly work night and day for you. Nora – bear sorrow and want for your sake. But no man would sacrifice his honor for the one he loves. NORA: It is a thing hundreds of thousands of women have done. Share on X NORA: It is your fault that I have made nothing of my life. our home has been nothing but a playroom. I have been your doll-wife, just as at home I was father's doll-child; and here the children have been my dolls. Share on XOur Critical Review

“A woman cannot be herself in modern society,” wrote Henrik Ibsen in his “Notes for a Modern Tragedy”, since it is “an exclusively male society, with laws made by men and with prosecutors and judges who assess feminine conduct from a masculine standpoint.”

“A Doll’s House” is one of the texts which changed that. Making our world, a century later, a bit more just and fair.

Outstanding.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.