The Double Helix Summary

8 min read ⌚

A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA

A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA

As far as you know, scientists are serious and rather dull guys in white coats doing experiments, talking gibberish and trying to get to the bottom of all things unexplained and seemingly unexplainable.

Enter James Dewey Watson, an ambitious 24-year-old American womanizer at Cambridge who’d go so far as to even filch an idea if Nobel-worthy. The name sounds familiar?

Probably because it was one of the first you learned in your biology class. Yup – that’s the guy who discovered the structure of DNA.

And “The Double Helix” is his thriller-like account of that immensely important scientific journey.

Who Should Read “The Double Helix”? And Why?

“The Double Helix” has everything a book should (and shouldn’t) have: determination and hunger for fame, against-all-odds story of success and caricatural portraits of famous people, friendships, betrayals, and even bigotry and chauvinism.

You should read it because you want to be a smarter fellow; after all, the discovery of DNA changed so many things about the world. Read it for the gossips and the unabashedly honest behind-the-scenes depictions of celebrated scientists – if you want juicy details from a world you taught had none.

Read it for the sheer joy of research – once you finish it, you’ll certainly get a better picture of the process by which scientists come across great discoveries. And read it for pleasure – if you are tired of novels and other types of fiction.

Because – sometimes – real life is just incalculably more interesting.

About James D. Watson

James D. Watson is an American geneticist, molecular biologist, and zoologist, a co-discoverer of the structure of DNA with Francis Crick.

is an American geneticist, molecular biologist, and zoologist, a co-discoverer of the structure of DNA with Francis Crick.

For this discovery, he shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with his partner and Maurice Wilkins, “for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material.”

He worked on Harvard for two decades (1956-1976) and served as either director or president of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory from 1968 to 2007. He resigned after making one possibly racist remark.

“The Double Helix Summary”

It was April 25, 1953.

If you were subscribed to “Nature” and opened the magazine on page 737, you would have come upon these two sentences:

“We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest.”

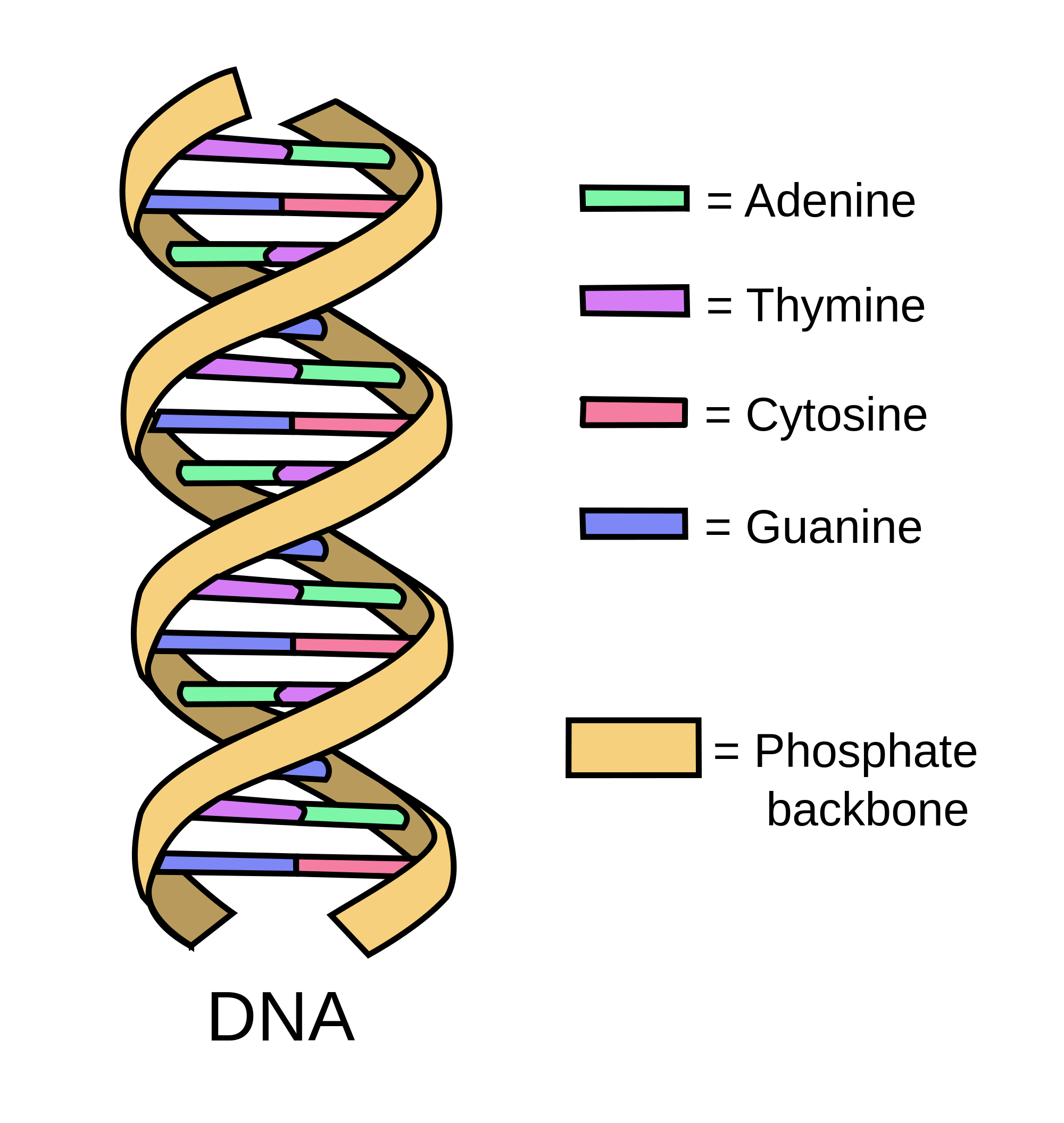

Above them, a descriptive combination of title and a subtitle: “Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid.” Below them – no more than 900 words and a simple “purely diagrammatic” figure unlike this one:

But beyond that – an event which will irretrievably change the course of history. Because what we just described was the article and the day the world first saw the double helical structure of the DNA we have grown accustomed to in the meantime.

If that doesn’t send shivers down your spine, let us rephrase that: 25 April 1953 was the day we discovered the secret of life.

Published a full decade and a half later, “The Double Helix” is James Watson’s personal account of this discovery.

You may think that it’s too scientific and unintelligible, too dull and mind-scratching for a person who doesn’t know anything about biochemistry.

But that only means that you don’t know James Watson.

A post-doctoral research fellow in Copenhagen, Watson was an ambitious man who wasn’t at all interested in the work of his mentor, Herman Kalckar. Fortunately for him, he accompanied Kackar to a meeting in Italy, where he heard Maurice Wilkins talk about his X-ray data on the structure of DNA.

So, the autumn of 1951, he went to Cambridge University and joined the group working in the Cavendish Laboratory. Officially – to work on three-dimensional structures of proteins. Unofficially – to make a discovery which will grant him a Nobel.

And, oh yes – to meet a “popsy” or twenty.

If you don’t want to lose time checking that word in your dictionary, let’s just say that it means precisely what you think it means: “an attractive young woman.”

After all, Watson was a man; and he was barely 23.

Now, when he wasn’t seducing Cambridge au pair girls, Watson was spending time with Francis Crick, who thought this book was all but a betrayal of their friendship. You think he may have overreacted? Well, this is the first sentence of the book: “I have never seen Francis Crick in a modest mood.”

There are many even harsher about practically every single person Watson ever met during this period. Himself included.

Anyway, Watson and Crick may have had dreams of greatness, but neither of them had any clue how they were supposed to be the first to discover the structure of DNA when everybody who meant something in the world of biochemistry at the day was trying to achieve the same thing.

To put it mildly, the odds were against them.

In London, Wilkins was working with Rosalind Franklin, gathering and analyzing data. And over the Atlantic, in Watson’s home country, Linus Pauling had been studying DNA for years. And – in case you forgot – Watson and Crick weren’t even supposed to be working on DNA models.

But, you know how it goes: scarcity breeds invention – especially after hours. And, as Machiavelli once said, the end justifies the means. Michael Scott’s alteration may be even more applicable in this case: the end justifies the mean.

First, Watson managed to get an invitation to a Franklin lecture, and then, after Linus Pauling’s latest theory was found to have fundamental flaws, went to Franklin’s lab and used, without her permission or knowledge, the best X-ray diffraction image of crystallized DNA available: Photograph 51.

Now, Watson and Crick were on to something. And everybody was aware that they were. The director of the Cavendish Laboratory, Sir Lawrence Bragg, announced the discovery on April 8, 1953, at a conference in Belgium.

The press didn’t even report the story.

But, after the “Nature” article and few talks by Bragg, by the next month, the world was in awe of the importance of the discovery. Watson and Crick were stars.

A decade later, they shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Wilkins.

Unfortunately, four years before that, Rosalind Franklin succumbed to the ovarian cancer she was suffering from, at the very early age of 37.

Key Lessons from “The Double Helix”

1. Sometimes You Need a Lot of Ambition and Stubbornness to Win a Nobel Prize

2. You Can Make Fundamental Mistakes – Even If You’re One of the Best Scientists in History

3. The 1950s Weren’t a Good Time to Be a Woman – No Matter How Smart

Sometimes You Need a Lot of Ambition and Stubbornness to Win a Nobel Prize

True, some scientists are in it for the potential contribution they can make to a better future for humanity. But, not few are in it for the money or the fame. And some – maybe even the majority of them – are in it because of all of that.

“The Double Helix” tells this in no uncertain terms. The reason why James Watson got interested in the study of DNA was not because of the importance of the discovery itself, but because he wanted to be the one to make it. In other words, even if Watson was working merely on his thesis, someone else would have undoubtedly discovered the model of DNA.

But, that was not the point. The point was that the discoverer would leave a mark in history and be remembered for all times.

Watson was a brilliant scientist with a brilliant mind, but he also had very human ambitions. Which, of course, meant that he felt excitement and joy the moment he realized that Linus Pauling made a fundamental flaw in his model of the DNA. “Though the odds still appeared against us,” he writes in “The Double Helix,” “Linus had not yet won his Nobel.”

And James Watson will win it because, against the Cavendish board advices, he will work after hours on his models. And because he will decide to use other people’s data instead of working on acquiring his own.

Bitter scientific rivalries?

You betcha!

You Can Make Fundamental Mistakes – Even If You’re One of the Best Scientists in History

Now, what happened with Linus Pauling?

He is, after all, a household name for a reason: the 16th greatest scientist in history (ahead of Curie, Hubble, Fermi, Euler…), Pauling is the only person ever to win two unshared Nobel Prizes. And at the time Crick and Watson had to borrow both time and money to work on the DNA model in hiding, he had both the funds and the equipment to work out a solution before everybody.

Not only he didn’t, but his model – triple helix – exhibited several serious mistakes and one fundamental flaw: a proposal of neutral phosphate groups.

You don’t need to understand what that means. You just need to compare the word “neutral” to the word which stands behind the last name of the DNA acronym: “acid.”

Now, how can anything – let alone a constitutive element – remain neutral in an acid environment, right?

Well, Pauling didn’t see that. He later stated several reasons which resulted in his mistakes, but, really, he shouldn’t have bothered. The fact is – he was merely human. And humans – even the best specimens – make mistakes.

Speaking of which: James Watson has incited a fair share of controversies himself.

The 1950s Weren’t a Good Time to Be a Woman – No Matter How Smart

Even though James Watson claims that the tragic figure in “The Double Helix” is Maurice Wilkins, that title, much more deservedly, goes to Rosalind Franklin, an X-Ray crystallographer whose data – especially, Photo 51 – was of crucial importance to the discovery of DNA.

She died of cancer four years before Watson, Crick, and Wilkins won the Nobel Prize. To add insult to injury, Watson paints her in “The Double Helix” in an unfavorable light. Not because she lacked something – but because she was a she, a woman.

In later years, Watson will repent doing that, claiming in an added epilogue that she had “honesty and generosity,” and that he had realized “years too late the struggles that the intelligent woman faces to be accepted by a scientific world which often regards women as mere diversions from serious thinking.”

Sounds like an oxymoron. But it’s the cruel reality women scientists had to face for most of the 20th century.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app, for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“The Double Helix Quotes”

In the end, though, science is what matters; scientists not a bit. (Steven Jones, from the Introduction) Share on X One must admit that his intuitive understanding of human frailty often strikes home. (Sir Laurence Bragg, from the Foreword) Share on X One could not be a successful scientist without realizing that, in contrast to the popular conception supported by newspapers and mothers of scientists, a goodly number of scientists are not only narrow-minded and dull, but also just… Share on X Worrying about complications before ruling out the possibility that the answer was simple would have been damned foolishness. Share on X Excitedly, I pilfered Bernal and Fankuchen’s paper from the Philosophical Library and brought it up to the lab so that Francis could inspect the TMV X-ray picture. Share on XOur Critical Review

James Dewey Watson’s “The Double Helix” – as Robin Mackie laconically states – “combines the plot line of a racy novel with deep insights about the nature of modern research.”

In the same article – which, by the way, uncovers how close we were to never having the privilege of reading Watson’s book – Mackie writes something almost everyone who has heard its title already knows: “The Double Helix” is “consistently ranked as one of the greatest books written about science in the past century.”

So consistently, in fact, that, by now, accolades are in the book’s DNA!

(Ha – see what we did there?)

We name just three: “The Double Helix” was placed on Library of Congress’ list of the 88 “Books That Shaped America.” It was voted the 7th best nonfiction book of the 20th century by the Modern Library. And the 15th by “Guardian.”

Sounds familiar?

Possibly because you’ve already encountered upon a similar description in our list of the “best nonfiction books of all time.”

Still need our critical review?

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.

A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA

A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA