When Women Ruled the World

13 min read ⌚

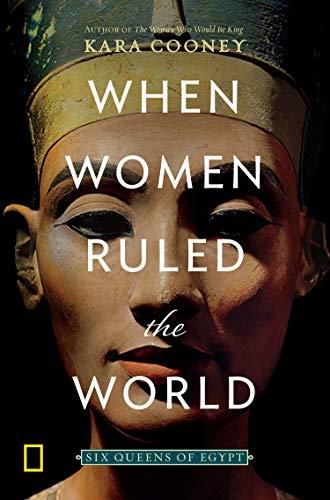

Six Queens of Egypt

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away, there were queens mightier than kings.

And Kara Cooney wants to talk to you about six of them, each of which left a lasting mark on Ancient Egypt.

Learn all about them in our summary of her book:

Who Should Read “When Women Ruled the World”? And Why?

If you are interested in history—especially in pharaohs and Ancient Egypt—then you should definitely have a look at When Women Rule the World.

But read it if you want to understand why women don’t rule the world at present, and why they should in the future: besides being a historical study, Kara Cooney’s When Women Ruled the World reads like a feminist manifesto as well, one mostly based on empirical data taken from the mother of all knowledge—history.

About Kara Cooney

Kara Cooney is an American Egyptologist, archaeologist, and associate professor of Egyptian Art and Architecture at UCLA.

A specialist in coffin studies, craft production, and economies in the ancient world, Cooney is the author of two books. Her debut before When Women Ruled the World was The Woman Who Would Be King and focused on Egypt’s most influential female pharaoh in history, Hatshepsut.

Cooney is also the host and producer of Discovery’s TV series, Out of Egypt.

Find out more at http://karacooney.squarespace.com/

Book Summary

“When Women Ruled The World” shows, in what seems mythical but is true, how your powerful women reconsider the culture of European monarchy during the sixteenth century.

In this game-changing revisionist history, a leading scholar of the Renaissance shows how four powerful women redefined the culture of European monarchy in the glorious sixteenth century.

To speak of women ruling the world nowadays seems a bit unreal. Maybe that’s why Kara Cooney begins her book on the most famous Egypt’s queens with a very telling fairytale stock phrase:

Once upon a time, there were women who ruled the world. Six of them—Merneith, Neferusobek, Hatshepsut, Nefertiti, Tawosret, and Cleopatra—climbed the highest and wielded the most significant power: not as manipulators of their menfolk, but as heads of state. Each started as a queen—a mere sexual vessel of their king—but each became the chief decision-maker, and five of them served as king outright. Though each woman must have had the gravitas, skill, intelligence, and intuition to rule, each was also put in power by an Egyptian system that needed her rule.

Now, make no mistakes: if it sounds too good to be true, that is because it is. Even Egypt, “the only state that consistently allowed female rule,” was, in the long run, “no less cruel and oppressive to women than every other complex society on Earth.”

It too had merely a few female rulers, and “suffered a woman leader only when it had to, expunging her from the eyes of her people as soon as possible.”

What does that mean?

It means that a woman could become a king only if the male king was too old or too young to rule—or, perhaps, hadn’t been born yet. It also means that no matter what these queens did, the pharaohs that came after them, consistently “erased or omitted their names from the formal ‘king lists’ of monarchs created by the royal temple.”

So, in short: the power was freely given to them because Egypt needed them. When it didn’t need them anymore, it acted as if these women never ruled.

In When Women Ruled the World, Kara Cooney tries to change this, so that we can better understand “this strange and contradictory tale of unadulterated female power wielded by poorly remembered women over an extraordinary 3,000-year run of ups and downs.”

So, let’s turn to the women themselves.

Merneith: Queen of Blood

Merneith was not only one of the first female rulers of Egypt—she was one of the first rulers of Egypt, period.

She ruled during Dynasty 1 (3000–2890 B.C.), at the very dawn of the Egyptian nation-state, when (as Cooney says) “kingship was new and brutal.”

When her father, the revered King Djer died, her brother Djet inherited the throne from him. Soon after, he asked Merneith to be his wife and, expectedly, she agreed. No need to reread the previous sentence: Merneith was now, indeed, both the sister and the chosen wife of the new pharaoh.

King Djet unexpectedly died only a few years in his reign, and his son with Merneith, Den, was too young to rule—so Merneith became the ruler instead.

Her first duty?

To properly prepare the burial for her husband and brother.

She did her best: per the ceremonial practices (which asked for sacrifices), she killed hundreds of people, most of them half-brothers of Den. The reason is apparent: she wanted to make sure that when Den became a Pharaoh, not one of his power-hungry relatives would be able to challenge his rule.

Though she never officially became the sovereign, Merneith ruled for Den for six or seven years and, when she died, she was honored with a king’s burial: 120 close relatives of her lie buried next to her in the royal necropolis of Abydos.

Neferusobek: The Last Woman Standing

Eleven dynasties after Merneith, Neferusobek (or Sobekneferu) of Dynasty 12 (1985–1773 B.C.) became the first female Pharaoh of which we have undeniable proof.

She was the daughter of Amenemhat III, a powerful ruler whose reign is deemed the golden age of the Middle Egyptian Kingdom. Additionally, just like Merneith, Neferusobek was also the wife of her brother, in her case, Amenemhat IV.

Unfortunately, due to this tradition of incestuous relationships, Amenemhat IV was sterile, so he didn’t leave a male heir after his death. That’s how Neferusobek, the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt, assumed the throne.

She remained there for no more than four years, a period during which she completed the construction of a temple complex in Hawara and added places of worship in structures at Heracleopolis Magna.

She died a mysterious death but was not forgotten: she was preserved in most of the king lists, and honored for protecting the land in a time of distress.

Hatshepsut: Queen of Public Relations

The second historically confirmed female pharaoh came to power four centuries after Neferusobek.

Her name was Hatshepsut (of Dynasty 18, 1550–1295 B.C.) and she was “the only woman to have ever taken power as king in ancient Egypt during a time of prosperity and expansion.”

That was not the only rule Hatshepsut broke.

Appointed to the office of High Priestess by her father Thutmose I as a young girl, Hatshepsut became the wife of her brother, Thutmose II, soon after he inherited the throne. Thutmose II accomplished absolutely nothing during his short reign and was supposed to be succeeded by a son born of his harem.

At the time of Thutmose II’s death, the boy, Thutmose III, was just a toddler, so his mother was supposed to act as pharaoh regnant. However, she (her name was Iset) was incapacitated, so Hatshepsut was assigned to the role. And she remained there a long, long time—22 years to be exact.

She seems to have been a very smart queen, doling out riches and titles to the men around her to appease them. She also built majestic religious buildings, such as the Temple of Millions of Years at Thebes, and a powerful Red Sea fleet which, in turn, made famous trading expeditions around Africa.

She went personally on the most well-known among these, the one to the Land of Punt, a semimythical place dubbed “the Land of God” by Ancient Egyptians. When she returned from this daring expedition with priceless aromas and spices, Hatshepsut was rewarded with the respect of her people.

Like her father, Hatshepsut also organized military expeditions and expanded Egypt’s borders to Nubia and Kush. She also raised a great king: the empire of Thutmose III would become the largest Egypt would ever see.

Unfortunately, Thutmose III was a bit ungrateful and destroyed every memory of his stepmother once he became the pharaoh. In Cooney’s words,

[Hatshepsut’s reign] was a reign marked by accomplishment, clever strategizing, empire building, and prosperity. But the next king was not her son; indeed, her lack of male offspring was what made her kingship necessary. Without a son to keep her legacy intact, her name was removed from the religious and historical record, her images scratched away, her statues smashed to pieces. Her rule was seen as a threat to the men who came after her—the very men she had personally placed into positions of power.

Nefertiti: More Than Just a Pretty Face

A century after Hatshepsut, Nefertiti, also of Dynasty 18, became the wife of Amenhotep IV, perhaps the instigator of the first monotheistic religious revolution in history.

In the fifth year of his reign, Amenhotep ordered a sed festival, even though this was a privilege only for the pharaohs who retained the throne for three decades. It was even stranger when he dedicated it to the sun god Aten, a minor god in Egypt’s polytheistic pantheon.

Little did the Egyptian elites know that this was merely the beginning: soon after, Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten (“The One Who Is Beneficial to the Aten”), and, before too long, he started destroying old temples and building new ones (all of them dedicated to the sun god), going so far to even order the erection of a new capital, Amarna.

Akhenaten seemed to have loved Nefertiti a lot—who wouldn’t have—which is why “The Great King’s Wife” had all the freedom she wanted. It is quite possible that she used it to reinvent herself, in the twelfth year of her husband’s rule, as Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten, his co-king.

She ruled with him for the next five years and, after his death, she may have reinvented herself yet again as Ankhkheperure Smenkhkare, the pharaoh who came next in line and who ruled before the boy-king Tutankhamun.

Egyptologists are not sure whether Ankhkheperure Smenkhkare was Nefertiti, but many think so. If that is the case, she successfully guided Egypt on a path to recovery after a period of great turmoil.

“Nefertiti is remembered to us as a great beauty, a chiseled face of loveliness and sensual desire,” writes Kara Cooney. “But she may have been much more if recent investigations are correct.”

Tawosret: The Survivor

During Dynasty 19 (1295–1186 B.C.), another woman named Tawosret became pharaoh. But she did so in a way none of her female predecessors did: “through her husband, an unrelated royal heir, and brutal civil unrest.”

Tawosret was the wife of Seti II, who was supposed to be the pharaoh of Egypt when he sat on the throne around 1200. However, at the same time, another man named Amunmesses (or Amenmesse), possibly his half-brother, seized control over Nubia and Thebes and announced his claim to the throne.

Seti II emerged victorious from the power battle that followed but unexpectedly died after trying to consolidate power in Thebes via Chancellor Bay. Bay installed a new king, a 14-year-old boy named Siptah, a guy too young and sickly (he had cerebral palsy) to rule at the time. So, he was placed under the guidance of Tawosret, the queen regent (and possibly his stepmother).

And this is where things got messy: Bay expected for Siptah to die soon (and, true, he died at 16) and to assume power himself. Tawosret had a plan of her own: she killed Bay and became the first female pharaoh to rule unaccompanied by father or husband or son.

She was killed by a warlord named Setnakht only two years after she became the sovereign. Just like Neferusobek, Tawosret was also the last ruler of her Dynasty.

“Her tomb in the Valley of the Kings,” informs us Cooney, “shows her as a female king, but that sepulcher would be taken over by the very same man who had her violently removed from power.”

Cleopatra: Drama Queen

During the millennium or so after Taworset, female power lay dormant in Egypt as parts of the country were repeatedly conquered by foreign powers. Unsurprisingly, Egypt’s last queen—and the most famous of the lot—was actually a foreigner: Cleopatra VII, a member of a Macedonian Greek ruling family (the Ptolemaic Dynasty which came after Alexander the Great and lasted from 305 B.C. to 30 B.C.).

When she was 14 years old, Cleopatra was named co-ruler of Egypt by Ptolemy XII, her father, who named his son Ptolemy XIII as his successor. However, Cleopatra’s brother wanted to rule Egypt all by himself, so he exiled Cleopatra to Syria.

Unfortunately for him, he allied himself with the wrong person, the Roman general Pompey who lost the Civil War in Rome to Julius Caesar. Cleopatra used the situation to charm Caesar and ask from him to force her brother to reinstate her as a co-ruler.

Ptolemy XIII refused, much to his misfortune, because that caused his demise: united, Cleopatra and Caesar won the war against Ptolemy, and Cleopatra became co-ruler with her younger brother, Ptolemy XIV.

As it is well known, Caesar’s weakness for Cleopatra resulted in Cleopatra’s first child, Caesarion, but also in her lover’s assassination. Cleopatra acted quickly: she poisoned her brother and positioned Caesarion as co-ruler in his place.

Moreover, she also started yet another affair, with one of Caesar’s former allies, Mark Anthony. She bore him children as well, and for a while, the institution of a Roman-Egyptian dynasty looked all but inevitable.

However, the feeling wasn’t shared by the powerful Roman elites, who, under the command of Octavian August, started a war against Marc Anthony and Cleopatra.

The final result?

When it was evident that the war—and, as Byron would say, “the ancient world”—was irretrievably lost, Anthony stabbed himself, Cleopatra poisoned herself in a bathtub, and Caesarion was killed by the Romans, taking her younger children hostage.

That marked not only the end of Cleopatra but, in a way, of Egypt’s glory as well.

Key Lessons from “When Women Ruled the World”

1. Divine Kingship: Egypt’s Political System

2. The Stories of Egypt’s Female Pharaohs

3. Why Women Don’t—And Should—Rule the World

Divine Kingship: Egypt’s Political System

In Egyptian mythology, the primeval king of Egypt, the god Osiris, passes his title on his son, Horus. Nothing strange—that’s how it is in almost all human cultures. A father king transfers his power to his son whose duty is to produce male offspring so that the country can be indefinitely ruled by powerful men.

However, Egypt was an exception to this rule, possibly because they worshipped almost as much as Osiris his wife and sister, Isis, “the alpha and omega of Egyptian kingship.” Queen and lover, nurturer and mother, Isis was the reason why, from time to time, women got to become pharaohs as well.

And we’re not stretching the truth here at all: since all of Egypt’s rulers, according to its unique system of power called divine kingship, were representatives of gods on earth, women pharaohs had to be adored by everybody as much as men pharaohs. After all, they were practically goddesses.

The Stories of Egypt’s Female Pharaohs

However, it is essential to note that, even though Ancient Egypt was the only country that consistently allowed women to become as powerful as men, it was still ostensibly a patriarchal and authoritarian society.

More or less, women could only become pharaohs when the designated king was either too young or too old to rule—or when he was not even born.

Be that as it may, the six women whose stories are told by Kara Cooney in When Women Ruled the World—Merneith, Neferusobek, Hatshepsut, Nefertiti, Tawosret, and Cleopatra—did manage to become the most powerful person in Egypt (all in their own times), and five of them served as king outright.

Why do we know so little of them today?

Because the men who came to rule Egypt after they erased their names from the formal ‘king lists’ of monarchs created by the royal temple.

You’d think that something like that doesn’t happen today—but it does. Think of Janet Reno or Janet Yellen. Just recently two of the most powerful people in the United States, both of them are practically forgotten today.

Why Women Don’t—And Should—Rule the World

“The Egyptians,” writes Cooney, “were light-years ahead of us in their trust of female power… We may be a 50/50 society in terms of gender, yet women do not hold 50 percent of the power.”

“Whether we want to admit it or not,” she goes on, “voting a woman into office makes most Americans feel uncomfortable, even threatened, because she appears more strident and shrill and bossy than her male counterpart, according to countless sociological studies.”

In other words, women don’t rule the world because we distrust them much more than their male counterparts. When Women Ruled the World uncovers that this was not always the case. On the contrary, in fact: Ancient Egypt fostered female ambition, and, that way, it was able to raise queens it was (at least for a short time) proud of.

With this in mind, Cooney is able to conclude:

The Egyptians knew that women avoid risk, steer clear of shock and awe. Women were regularly chosen as pharaoh for this very reason. They don’t typically wage war, rape, or throttle; they rule pragmatically; they don’t hog all the credit. Society won’t let them. They avoid owning their ambition; society would excoriate them for displaying it. In Egypt, such women were the salvation of a people again and again. We should let ancient history be our guide and let women be our salvation once more.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“When Women Ruled the World Quotes”

In one place on our planet thousands of years ago, against all the odds of the male-dominated system in which they lived, women ruled repeatedly with formal, unadulterated power. Share on X Even if she could produce no sons, Neferusobek was the mechanism by which the elites could fashion a solution to their power vacuum—because a woman rules differently from a man. Share on X Despite all the successful sexual strategy, the battles won, the children brought up, the alliances made, Cleopatra failed nonetheless. Share on X It’s important to recognize that divine kingship—of Osiris or Horus, or of Jesus as king of the Jews—automatically demands divine queenship to protect it. Share on X In competitive and decentralized societies like our own, even brilliant and educated women are sometimes blocked from the start by our own misperceptions of their intentions. Share on XOur Critical Review

When Women Ruled the World is the perfect combination of historical research and down-to-earth language.

Informative and enjoyable in a novel-like fashion, it is an excellent book to start exploring the world of Egyptian female pharaohs—if not the world of Egypt’s divine kingship system itself.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.