The Communist Manifesto

10 min read ⌚

Our “The Communist Manifesto Summary” aims to tell you everything you need to know about the booklet which launched a thousand revolutions and, for a while, burnt the topless towers of capitalism.

Our “The Communist Manifesto Summary” aims to tell you everything you need to know about the booklet which launched a thousand revolutions and, for a while, burnt the topless towers of capitalism.

And love it or hate it, “The Communist Manifesto” is undoubtedly one of the most essential and influential nonfiction books ever written.

Commissioned by the Communist League and published in London in February 1848, this little book of no more than a hundred pages, changed the world as much as any other book in the history of humankind.

It inspired thinkers and philosophers; it generated revolutions and violent overthrows worldwide.

And it’s still as relevant as when it was first published.

But what is “The Communist Manifesto”? Who wrote it and why did it make such a fuss in so many countries? And do you really need to know about it even today, when communism is part of a tumultuous but largely forgotten past?

Read on to find out!

Who Should Read “The Communist Manifesto”? And Why?

“The Communist Manifesto” – officially known as “The Manifesto of the Communist Party” – was published in the most revolutionary year in human history, 1848.

Its main objective was to present a digested analysis of capitalism and its inherent faults, briefly outlining the ways in which capitalism will be superseded by a new stage in human history, socialism. (Francis Fukuyama would beg to differ.)

Written in a rousingly poetic manner, “The Communist Manifesto” would rise from initial obscurity to become a rallying cry for a host of unsatisfied masses.

And come the 20th century, this booklet will basically become a Bible for half the world. Nowadays, it’s lauded by some for its prophetic power, and blamed by others for the deaths of millions.

Either way, don’t be one of those guys who just say things based on second-hand non-objective sources.

Read “The Communist Manifesto” because, as Peter Osborne says, it is “the single most influential text written in the nineteenth century.”

And, yes, that’s the century which gave us Tolstoy and Dickens, not to mention Darwin’s “Origin of Species” and the theory of evolution!

Also, because it’s really brief. And can change the way you think. No matter which side you are on.

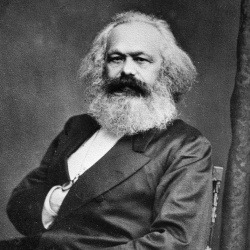

About Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Karl Marx was a German polymath, one of the most important intellectuals in human history. He was a philosopher and a historian, an economist and a political theorist.

was a German polymath, one of the most important intellectuals in human history. He was a philosopher and a historian, an economist and a political theorist.

Nowadays, he is chiefly remembered as the author of “The Communist Manifesto” and the gargantuan three-volume “Capital,” the foremost economic and political analysis of the inner workings of capitalism.

Both books are widely read and discussed year in year out, making Marx, by a wide margin, “the most influential scholar in history.”

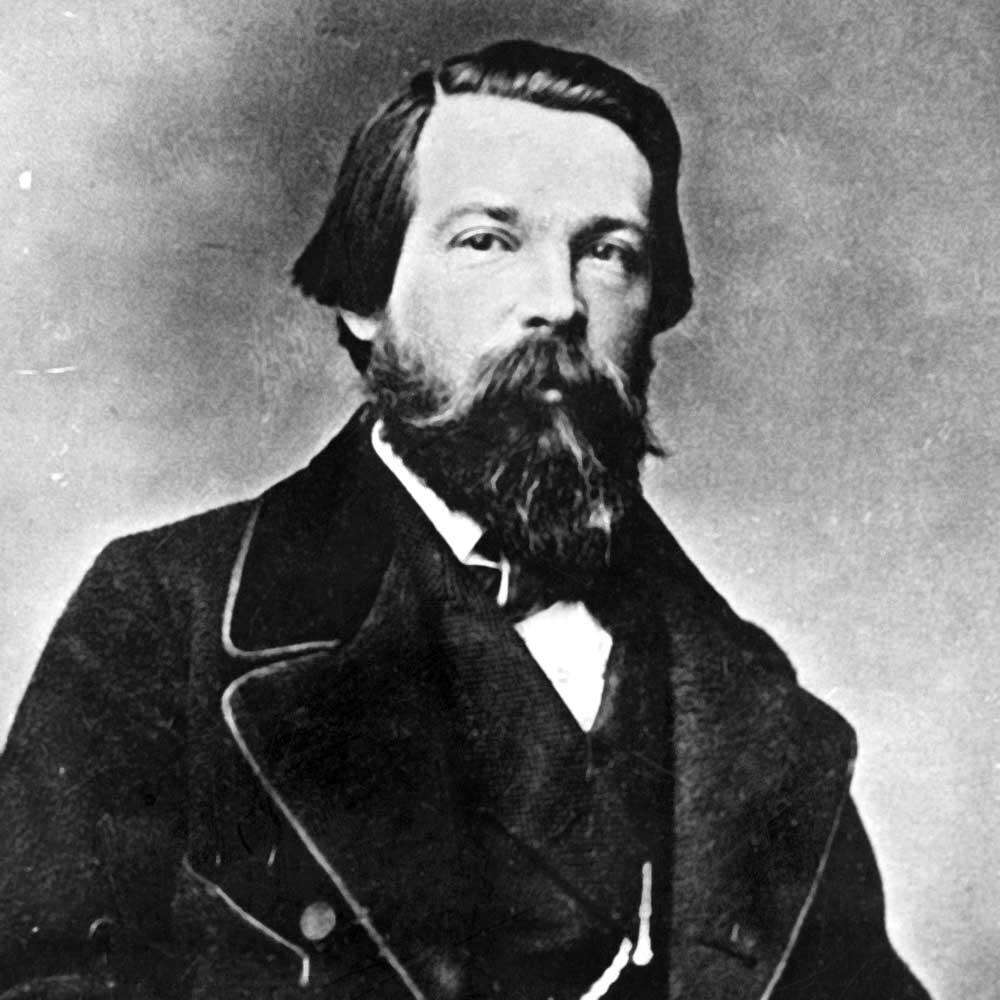

Friedrich Engels – sometimes anglicized as Frederick Engels – was a German philosopher, social scientist, and businessman.

– sometimes anglicized as Frederick Engels – was a German philosopher, social scientist, and businessman.

Engels’ father was an owner of a large textile factory in Manchester, England, but, influenced by Hegel and other thinkers, Friedrich grew up as a liberal-minded thinker.

To turn him away from this path, his father sent him to work at the factory. This, however, would have the opposite effect on Engels, inspiring him to write “The Condition of the Working Class in England.”

Marx was profoundly impressed by the book, and ever since 1844, he and Engels were inseparable collaborators and lifelong friends. Engels edited and published the second and the third volume of “Das Kapital” after Marx’s death.

“The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State,” possibly the first major work on family economics, is one of the few books Engels would write on his own afterward.

“The Communist Manifesto PDF Summary”

Both the Preamble to “The Communist Manifesto” and the pamphlet itself begin with widely quoted sentences.

The opening words to the former are the following: “A specter is haunting Europe — the specter of communism.

All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this specter: Pope and Tsar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies.”

Marx’s and Engels’ takeaways from this observation?

First of all, that communism, even as a somewhat spontaneous movement, is already acknowledged as a power by the whole of Europe; and secondly, that, if it so, it’s time for the communists to make their views known to the world.

And that’s when Chapter 1, “Bourgeois and Proletarians” commences. Its opening sentence – “The history of all hitherto societies has been the history of class struggles” – sets the tone of the discussion which follows. Namely, that throughout all history, there are people who rule and people who are ruled.

As Marx writes in continuation, “Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, that each time ended, either in the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.”

At the time when Marx and Engels were writing, the oppressive minority was the bourgeoisie which controlled the means of production.

They themselves were once oppressed, but thanks to their entrepreneurial spirit, and fueled by the discovery of America and the French Revolution, they came out on top during their struggle against the feudal landowners of before.

And by the middle of the 19th century, they became so powerful that, basically, they were the ones controlling the state affairs – not the other way around. “The executive of the modern State,” write Marx and Engels, “is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.”

However, if history taught us anything, the bourgeoisie was about to become a thing of the past as well. Because, so as to increase their own capital, they had to exploit the workers more and more.

And the workers – Marx and Engels call them proletarians – will undeniably one day become aware of their potential and rebel.

“What the bourgeoisie, therefore, produces,” conclude the German writers, “is its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.”

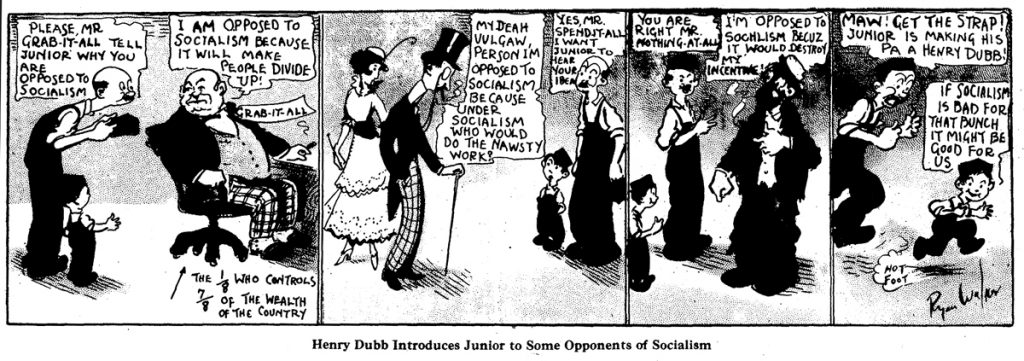

Ryan Walker, an American socialist and cartoonist, presented how this will happen in a funny little cartoon drawn in 1915.

Not much has changed to this day, has it?

Oh, wait: it has! And it will – for the worse. In the very same direction, Marx and Engels predicted.

Now, one may argue that the first chapter of “The Communist Manifesto” is by far the most read, discussed, and interesting one. However, it merely presents the theory, a materialist conception of history debated ever since.

And Marx himself wrote – one more time, memorably – just three years before the Manifesto, in the eleventh and final thesis on Feuerbach that “philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”

Well, that’s where Chapter 2, “Proletariats and Communists,” comes in handy.

After reassuring that the communist philosophy is, in its essence, a philosophy of the proletariat, it’s here that Marx and Engels present the practice, the actual changes which communists intend to implement once they come to power.

Noting that different measures should be taken in different countries, “The Communist Manifesto” lists ten measures which, as it claims, should be “generally applicable” in “most advanced countries.”

First of all: abolition of property in land and abolition of all rights of inheritance. In other words, eradication of the concept of private property. This should, of course, come at a price – namely, the confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

Then, a heavy progressive task – which, even today, may be our only way to decrease inequality.

Fifth and – the establishment of a national bank with an exclusive monopoly. Next, centralization of the means of communication and transport.

Seventh – “extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State.” Followed by an attempt to create “equal liability of all to work” and gradual abolition of the distinction between town and country.

Finally, the abolition of children’s factory labor and the granting of free education for all.

Now, here’s a summary of a book written after the financial crisis of 2008-9! Interestingly enough, even today, some of these measures still make a lot of sense.

The third chapter of “The Communist Manifesto” is titled “Socialist and Communist Literature,” and is Marx’s and Engels’ way of distinguishing the communist movement against other social and socialist movements of the day.

Communism is here presented as the proletariat’s only viable option because other movements fail to recognize the existence of class struggle and/or the need for a violent revolution to overthrow the oppressive classes.

Finally, the fourth chapter, “Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Opposition Parties,” announces the international character of communism, describing the struggles in few European countries at the time of writing and listing the existing parties and movements communists support in each of them.

Once you read it, it’s highly likely you will never forget the final paragraph of the pamphlet:

“The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions.

Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win! Working men of all countries, unite!”

Key Lessons from “The Communist Manifesto”

1. All History is a Class Struggle

2. A Communist Revolution Should Establish the First Classless Society in History

3. So, How Right Were the Young Marx and Engels?

All History is a Class Struggle

As it states in the very first sentence, “The Communist Manifesto” attempts to show that whole history is a struggle between the ruling and the ruled classes.

Once the former were patricians and the latter plebeians, recently they were lords and serfs.

However, the underlying philosophy is the same: very few people have much, and the many have all too little.

What Marx and Engels noticed is that each of these periods of history ended when the inequality reached a point at which the latter had nothing to lose but their chains.

So, peacefully or violently, they rebelled. And became the new masters.

A Communist Revolution Should Establish the First Classless Society in History

At the time that Marx and Engels were writing “The Communist Manifesto,” the bourgeoisie was the ruling class, and the proletariat the ruled one.

The former had the means of production and the money, while the latter earned very little, working most of their day.

In Marx’s and Engels’ opinion, there’s no way that this will be the final stage of history.

At one point, the proletariat will realize that they are producing much more than the whole world would ever need – and will put an end to being exploited.

The sooner – say Marx and Engels – the better for them and their children.

Because the new society they are proposing – based on the abolition of private property – should be a society of equals.

“In place of the old bourgeois society,” write Marx and Engels,” with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.”

So, How Right Were the Young Marx and Engels?

A little perspective:

In 1848, most of the people considered things such as slavery or child labor to be just ways to gain an advantage in the free market.

Together with few other related factions, communism was one of the first political movements to advocate for the abolition of such practices, in addition to promoting free education for all as the only way for people to be aware of their rights and freedom.

However, the young Marx and Engels didn’t bother to find a way to establish such a society without violence.

And though they predicted virtually everything which has since happened in capitalist countries, they predicted almost nothing of the things which occurred in communist ones.

Nor that there may be some other, more peaceful way by which capitalism should eventually evolve into socialism.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app, for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“The Communist Manifesto” Quotes

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Share on X A specter is haunting Europe—the specter of Communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this specter; Pope and Czar, Metternich and Guizot, French radicals and German police spies. Share on X All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away; all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is… Share on X Modern bourgeois private property is the final and most complete expression of the system of producing and appropriating products, that is based on class antagonisms, on the exploitation of the many by the few. Share on X Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Workingmen of all countries unite! Share on XOur Critical Review

Some of the ideas presented in “The Communist Manifesto” haven’t aged well. Others have aged just like a fine wine.

Speaking of the latter, academic John Raines wrote in 2002 that nowadays, when the “Capitalist Revolution has reached the farthest corners of the earth” and “the tool of money has produced the miracle of the new global market and the ubiquitous shopping mall,”

“The Communist Manifesto” seems like a prophetic work. Read it, he adds “and you will discover that Marx foresaw it all.”

You don’t really need to agree with Raines. But, we think that it would be good if you disagree only after reading through this book.

The best part is – it’s in public domain and you don’t even have to buy it. Here’s one of the many translations, available online, both as a text and as audio, but also downloadable as The Communist Manifesto PDF.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.