Between the World and Me Summary

11 min read ⌚

Ta-Nehisi Coates is widely regarded as “the single best writer on the subject of race in the United States.” And Toni Morrison says that this book-length letter from him to his son is “required reading.”

Should we say more? Ladies and gentlemen, we present to you the summary of:

Who Should Read “Between the World and Me”? And Why?

If you are interested in US politics or history, then it is only fair that you hear it told through the mouths of those who were silenced for centuries (and are still silenced throughout the country). Especially if they are as eloquent and argumentative as Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Also, if you are a black man and want to hear all about the realities that face you in America, then Between the World and Me is the best place to start your journey to self-discovery.

About Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates is an American journalist and writer.

A national correspondent for “The Atlantic,” he has also worked for “Time” and “The Village Voice” and “Time” and has written text for numerous other publications.

He is, however, most famous for his books: The Beautiful Struggle, Between the World and Me, Black Panther, We Were Eight Years of Power (a collection of essays), and The Water Dancer, his first novel.

Find out more at https://ta-nehisicoates.com/

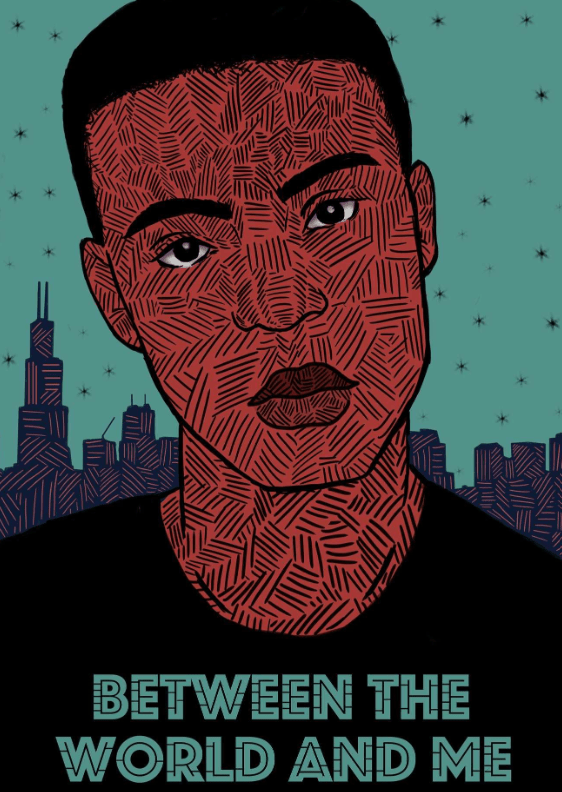

“Between the World and Me Summary”

Emulating the structure of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ poetic, touching and piercingly accurate analysis of “racist violence that has been woven into American culture” takes the form of a letter addressed from the author to his fifteen-year-old son, Samori.

The letter is divided into three chapters, the first of which recounts Coates’ experiences as a young man, the second of which talks about his life after the birth of Samori, and the last one of which narrates the author’s visit of Mabel Jones, a grieving mother of a mistakenly murdered African-American friend of Coates.

And we have all of them covered in our summary!

Chapter I

Naming “the People”

Coates begins his letter to Samori by describing an event from the Sunday before: a host of a popular news show asking him what it means to lose his body.

“Specifically,” the author goes on, “the host wished to know why I felt that white America’s progress, or rather the progress of those Americans who believe that they are white, was built on looting and violence. Hearing this, I felt an old and indistinct sadness well up in me. The answer to this question is the record of the believers themselves. The answer is American history.”

In other words, Coates says that the great country of America exists in large part due to the fact that part of its population was never given the chance to exist. Though Americans deify democracy almost as much as God, most of American history is extremely undemocratic.

In fact, when President Lincoln declared, in 1863, that the battle of Gettysburg must ensure “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth,” he didn’t have Coates’ grandfather in mind.

According to the laws of the time, Coates’ grandfather, simply and brutally put, wasn’t a person, wasn’t part of the people:

But race is the child of racism, not the father. And the process of naming ‘the people’ has never been a matter of genealogy and physiognomy so much as one of hierarchy. Difference in hue and hair is old. But the belief in the preeminence of hue and hair, the notion that these factors can correctly organize a society and that they signify deeper attributes, which are indelible—this is the new idea at the heart of these new people who have been brought up hopelessly, tragically, deceitfully, to believe that they are white.

The American Dream Is Deeply Rooted in Violence

“I write you in your fifteenth year,” says Coates a little below.

“I am writing you because this was the year you saw Eric Garner choked to death for selling cigarettes; because you know now that Renisha McBride was shot for seeking help, that John Crawford was shot down for browsing in a department store.”

“And you have seen men in uniform drive by and murder Tamir Rice, a twelve-year-old child whom they were oath-bound to protect. And you have seen men in the same uniforms pummel Marlene Pinnock, someone’s grandmother, on the side of a road.”

All these people—Garner, McBride, Crawford, Brown, Pinnock—were, tautology intended, people, regardless of the color of their skin. And yet, they weren’t treated as such. In the 21st century. By the most democratic nation on the planet.

The discrepancy is staggering and yet it is an indelible part of the society of the USA, a key component of American history.

It is what the American Dream is built upon: dig deep enough below the promises of success and the rags-to-riches Horatio-Alger-like stories, and you’ll find African-American bodies, lifeless, whipped, crunched, chomped, trampled.

Can you blame black people now for living in a constant state of fear, for talking about the extents of an ancient injustice or for fighting against mass incarceration?

The Sleeping Pill

Remembering the violence that surrounded him when he was young, Ta-Nehisi Coates advises his son to “resist the common urge toward the comforting narrative of divine law, toward fairy tales that imply some irrepressible justice.”

America is, simply put, violent, but it is all African-Americans have. And if they want to change something, they must try to change it actively here on earth, and not allow to be passivized by stories that claim that things will change themselves for the better with time or via some divine intervention after death.

It is this, this “language of intention,” which makes everything worse.

“The point of this language of ‘intention’ and ‘personal responsibility’ is broad exoneration,” warns Coates. “Mistakes were made. Bodies were broken. People were enslaved. We meant well. We tried our best. ‘Good intention’ is a hall pass through history, a sleeping pill that ensures the Dream.”

As far as Coates is concerned, Martin Luther King’s call for nonviolent resistance is a corollary of this type of worldview. He prefers the way of Malcolm X and the wake-up call of the Black Panthers—just like his father did in the 1970s, eventually becoming a local captain of their Party.

Nowadays, Paul Coates works as a research librarian at Howard University, where his son, Ta-Nehisi, by his own admission, finally found himself. Dubbing Howard his Mecca, he talks of how it was there that he learned everything he now knows of race and racial divisions—or, rather, the artificiality of the notions.

“I was made for the library, not the classroom,” he writes. “The classroom was a jail of other people’s interests. The library was open, unending, free.”

During this time, Ta-Nehisi meets Kenyatta Matthews. At 24, she becomes pregnant with his child. Nine months later the recipient of this letter is born. He is named after Samori Touré, a Guinean Muslim cleric who resisted French colonial rule in West Africa between 1882 and 1898 and died in captivity at the turn of the century.

Chapter II

The Murder of Prince Jones

A month after the birth of Samori, a classmate of Ta-Nehisi and Kenyatta from Howard, Prince Jones, is killed by the Prince George’s County police.

The officer, working undercover, had been sent out to track a 5 foot 4, 250-pound drug dealer. However, he eventually shot the 6 foot 3, 211-pound Prince Jones, just yards in front of his fiancé’s house. There were no witnesses. The charges against him were dropped for no reason whatsoever.

Coates and his wife went to Howard for their friend’s memorial. At the funeral, Ta-Nehisi couldn’t bear the atmosphere of mercy and forgiveness. After all, the police officer was incompetent and dishonest, and Prince Jones was a deeply religious and kind person.

Why should anyone forgive the former and not rage in calls for revenge for the death of the latter?

The Terror Before September 11

After moving to New York in 2001, two months before September 11, Ta-Nehisi started feeling anxious and “out of sync with the city.” The reality of this feeling becomes apparent to him on the day of the terrorist attacks.

“Everyone knew someone who knew someone who was missing,” he writes. “But looking out upon the ruins of America, my heart was cold. I had disasters all my own. The officer who killed Prince Jones, like all the officers who regard us so warily, was the sword of the American citizenry. I would never consider any American citizen pure.”

How could he?

Southern Manhattan was always Ground Zero for the Blacks: they had not only been auctioned there but they had also been buried under those very same ruins.

“Bin Laden was not the first man to bring terror to that section of the city,” Coates writes to his son. “I never forgot that. Neither should you.”

Samori’s Experiences with Racism

Even before he became aware of it, Samori experienced how deeply engraved racism is within the fabric of American society.

For example, once he was manhandled by a white woman at a movie theatre on the Upper West Side. After Coates reprimands her, a white man intervenes. Coates experiences this as “his attempt to rescue the damsel from the beast.” The man had made no such attempt on behalf of his son.

After being pushed by Coates, the man said to him something frightening: “I could have you arrested!” Coates thinks he knows what the sentence means: white people are still in control, and they have all the power they need over his and other black bodies.

Just like they always had.

That’s precisely what Coates tells Samori and his cousin during a visit of the historical sites from the Civil War when Samori is ten years old: in the eyes of the African Americans, this wasn’t a noble, heroic endeavor.

And that’s precisely what Samori can experience himself during a visit of a mother of a boy killed by the police: shouldn’t the police be protecting them?

They should—but, if you are Black, you better don’t give them a reason to change their minds:

So I feared not just the violence of this world but the rules designed to protect you from it, the rules that would have you contort your body to address the block, and contort again to be taken seriously by colleagues, and contort again so as not to give the police a reason. All my life I’d heard people tell their black boys and black girls to ‘be twice as good,’ which is to say ‘accept half as much.’ These words would be spoken with a veneer of religious nobility, as though they evidenced some unspoken quality, some undetected courage, when in fact all they evidenced was the gun to our head and the hand in our pocket. This is how we lose our softness. This is how they steal our right to smile.

Chapter III

The last chapter of Coates’ three-part book-length letter to Samori concerns Ta-Nehisi’s visit of Dr. Mabel Jones, the mother of the murdered Prince Jones.

Well-composed, “lovely, polite, brown,” Dr. Mabel Jones was born in Louisiana, which means that she had experienced racism firsthand ever since her earliest years. However, she manages to overcome all obstacles, excelling at school, winning a scholarship to Louisiana State University, and becoming (probably) one of the first black radiologists in American history.

Noticing his intelligence early on (“he was that caliber of a student”), Mabel had hopes that Prince would go to Harvard or another Ivy League School but chose to go to Howard instead. He just didn’t want to represent to other people anymore: he went to Howard to be normal, and “even more, to see how broad the black normal really is.”

Coates asks Mabel if she ever regretted Prince choosing Howard. “No,” she says, almost hurt. “I regret that he is dead.” Coates follows up this question with another one—if she expected that the police officer who had shot Prince would be charged. She says, “Yes.”

But he wasn’t—just like so many other police officers who have done and will do the same. Because, no matter how hard the African-Americans try to succeed, the shadow of their race hangs upon their heads like a blade.

One racist act is all it takes for a black person to lose his or her personhood.

“There he was,” Mabel says to Coates, speaking simultaneously of Solomon Northup from 12 Years of Slave and her son. “He had means. He had a family. He was living like a human being. And one racist act took him back. And the same is true of me. I spent years developing a career, acquiring assets, and engaging responsibilities. And one racist act. It’s all it takes.”

Coates leaves with a bitter taste in his mouth. He is devastated that modern technology has allowed the Dreamers to take control of the story behind the Dream and erase the part about how much of it is built upon black bodies.

As he is driving home, he watches through the window of his car the ghettos of Chicago (“the same ghettos where my mother was raised, where my father was raised”), and the old fear from his childhood overwhelms his body.

Key Lessons from “Between the World and Me”

1. The American Dream Was Built Upon Black Bodies

2. Bin Laden Wasn’t the First Terrorist in Manhattan

3. The Reality of Having a Black Body

The American Dream Was Built Upon Black Bodies

The American Dream is the national ethos of the United States, what this great country was built upon. However, it is also a nightmare for a large part of America’s population, who was never even considered to be part of the population for most of the country’s history.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is adamant that the only reason why there is such a thing as the American Dream is the exclusion of African-Americans from the idea: you can only build something so big and naïve on other people’s backs, and the Blacks have been forced to borrow theirs for centuries.

Bin Laden Wasn’t the First Terrorist in Manhattan

In one of the most controversial parts of the book—questioned by none other than Michiko Kakutani—Coates says that, while America grieved over the victims of the September 11 attacks, his heart was cold, because he was very much aware that Bin Laden wasn’t the first terrorist to murder Americans in Manhattan.

Just a century ago, under the very same rubble, African-Americans were either auctioned or murdered by rich white people who are probably still as rich and as white. Manhattan was always the Ground Zero for Blacks.

The Reality of Having a Black Body

Above everything else, Between the World of Me reveals that the reality of having a black body today is just a bit less bleak than the reality of having a black body a century ago.

African-Americans are still being killed for no reason by people who are never charged, let alone imprisoned.

And, still, all it takes is just one racist act for an African-American man to lose absolutely everything he has achieved in the blink of an eye.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Between the World and Me Quotes”

I would not have you descend into your own dream. I would have you be a conscious citizen of this terrible and beautiful world. Share on X You are growing into consciousness, and my wish for you is that you feel no need to constrict yourself to make other people comfortable. Share on X Race is the child of racism, not the father. Share on X Black people love their children with a kind of obsession. You are all we have, and you come to us endangered. Share on X To yell ‘black-on-black crime’ is to shoot a man and then shame him for bleeding. Share on XOur Critical Review

According to A. O. Scott of The New York Times, Between the World and Me is not only an important book, but “essential, like water or air.” And, unsurprisingly, in addition to being a #1 New York Times bestseller, the book was also named one of the ten best books of 2015 by almost any serious publication.

It eventually won the 2015 National Book Award for Nonfiction and was shortlisted for the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction (it lost to Black Flags). And just recently, as another proof of its significance, the book was ranked #7 on Guardian’s list of “100 Best Books of the 21st Century.”

Do you really need another recommendation?

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.