Just Mercy Summary

12 min read ⌚

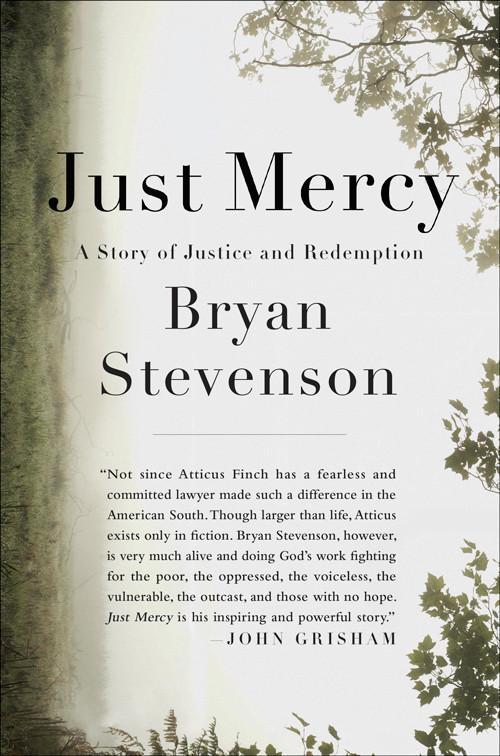

A Story of Justice and Redemption

In a March 2012 TED Talk, Bryan Stevenson—USA’s Mandela—reminded the world that, instead of believing everything is right with the world, it needed to talk about injustice and start doing something about it.

In retrospect, it sounds as if he was preparing the ground for the other, more important part of the story—the flip side of it, if you will.

Because Just Mercy, as both its title and subtitle suggest, is a story of justice and redemption.

And it’s one of the most important of its kind you’ll ever have the chance to read if you are an American!

Who Should Read “Just Mercy”? And Why?

Just Mercy is the book everyone who believes that the modern-day US-based version of Themis wears a blindfold should read straight away. Especially if he/she is a lawyer or judge.

It is also a book for those who know that America’s criminal justice system is flawed. Read it to not only see the extent of its unjust nature but also to detect the root cause.

About Bryan Stevenson

Bryan Stevenson is an American lawyer, social activist, and bestselling author.

A clinical professor at New York University School of Law, Stevenson is also the founder and executive director of Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit organization that provides legal representation to marginalized prisoners who may have been wrongly convicted.

Widely considered “one of the most brilliant and influential lawyers of our time,” Stevenson has received over 40 honorary doctoral degrees and won numerous awards, including the prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Prize, and the ABA Medal, the American Bar Association’s highest honor.

Find out more at https://justmercy.eji.org/.

“Just Mercy Summary”

Recently adapted into a touching and critically acclaimed legal drama starring Michael B. Jordan and Jamie Foxx, Just Mercy, for the most part of it, tells the story of Walter McMillian, a wrongfully convicted African-American pulpwood worker, whose controversial case received nationwide attention thanks to the efforts of none other than Bryan Stevenson.

However, though McMillian’s story is certainly its backbone, Just Mercy the book offers much more than the movie of the same name. It not only contains profiles of many other similar cases, but it also highlights the serious faults of the American justice system and suggests how they can be mended.

In a way, it is a very unique coming-of-age story that follows, across more than two decades, the fight of an idealistic and gifted young lawyer against the Leviathan that is the American legal system, still deeply rooted in bias and prejudice, still favoring the wealthy and the powerful over the poor and the helpless.

There is a way out, suggests Stevenson, offering a ray of hope for those of us who’ve lost it—and, believe it or not, it’s both rational and humane one.

Read ahead to find out more about it!

Bryan Stevenson, a Real-Life Modern-Day Atticus Finch

If you have an HBO subscription, allow us to make a recommendation: watch the documentary True Justice as soon as possible.

As the movie’s subtitle says, it is a biography of Bryan Stevenson and it documents his decade-long fight for equality. As such, it makes Just Mercy even more intelligible and emotional.

In short, Stevenson was born to an underprivileged black family in “poor, rural, racially segregated settlement on the eastern shore of the Delmarva Peninsula, in Delaware.” Though this was just a little more than half a century ago, it was Delaware, and Stevenson had to deal with racism ever since his earliest years.

He studied at a “colored” elementary school and his life didn’t get better even after the formal desegregation: black children continued to play separated from white children, and they had to wait at the backdoor at the doctor’s or the dentist’s office!

Unsurprisingly, Stevenson grew up wondering how just it is for black and poor children to be treated as second-rate citizens: if anything, it should be the other way around because they were powerless and they needed help.

But he was never one of those who favored revenge over redemption—and he didn’t change this stance even after his maternal grandfather was stabbed to death when he was sixteen.

After graduating from Eastern University in St. Davids, Pennsylvania, Stevenson received a full scholarship to attend Harvard Law School, but his real career began while interning with the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee (SPDC).

Over the course of this internship, Stevenson has the privilege of meeting and befriending Henry, a young black man with a wife and kids, Bryan’s very first death row inmate acquaintance.

The encounter has a transformative effect on Stevenson: he realizes that what he wants to do in life is to fight against the death penalty and for the reformation of America’s cruel and unjust prison system.

So as to achieve this, he moves to Atlanta to work for the SPDC. After some time, he moved yet again to Montgomery, Alabama, where, in 1989, he founded the Equal Justice Initiative—or EJI for short—an organization with a mission to “guarantee legal representation to every inmate on the state’s death row.”

Numbers Don’t Lie: The New Jim Crow

A year or so after moving to Atlanta, Stevenson was able to find (and afford) an apartment of his own. Since it was on a dense residential street, some nights he had to park halfway down the block (or even around the corner) to find a space.

However, one night, he got lucky and found a space just steps from his new front door. To make things even better, the radio was playing one of his favorite songs: “Hot Fun in the Summertime” by Sly and the Family Stone.

Bryan relaxed and decided to remain in the car for a couple of minutes and enjoy listening to the music. Not exactly, the perfect setting for the horror that followed: before Stevenson knew it, a SWAT team had surrounded his car, pointing guns at him and blaming him for a burglary.

They never apologized after letting him go. “You should be happy,” the older officer said to him, frowning.

Believe it or not, the officer was right: Bryan was pretty fortunate not to be imprisoned for, well, doing nothing while being black. Because, as Michelle Alexander demonstrates in her exceptional and aptly-titled book, The New Jim Crow, most African-Americans usually are and in quite similar situations.

And this is not an exaggeration: based on the stats, 1 in 3 African-Americans born in the 21st century will end up at least once in prison during his life!

Now, how is that possible?

Well, two reasons, and they can be summed up in three words: drugs, Reagan, and jurors.

You see, mass incarceration is a relatively new phenomenon, and it really hit off after Reagan started his War on Drugs, which was, in fact, war on minorities. During and after his time, prison population rose significantly, mostly because of all the black people put there for smoking marijuana or something similar.

Though, statistically, white people use drugs at much the same rate, it was mainly the African-Americans who ended up being imprisoned because the jurors were (and still are) mostly white men—even in counties with majority black populations.

Why are so few black people jurors even though ever since 1880 it has been unconstitutional to exclude jurors on the basis of race?

Well, because most of them have been convicted of some minor crime and, thus, are more often than not ineligible!

It’s a vicious circle and it spells out Injustice with a capital I!

The Story of Walter McMillian

Just Mercy contains numerous stories of wrongfully or harshly convicted people from all walks of life.

On its pages, you’ll come across a young mother serving a decade-long prison sentence for writing five checks—none more than $150—or across Charlie, a 14-year-old boy sentenced to life in prison for killing his mother’s abusive boyfriend.

However, by far the longest and most important story is that of Walter McMillian which is so fraught with the failings of the justice system that it almost reads like an allegory.

Unfortunately, it is a true story and yet another one about a wrongfully convicted African-American man coming from a poor community in Monroeville, Alabama.

The Murder of Ronda Morrison

Though he had spent most of his childhood picking cotton, Walter managed to become a “moderately successful businessman” by the time he was 45. By this time, he was also a married man with children.

However, in the community, he was best known for the affair he had with Karen Kelly, a white woman, and for the fact that his son had married a white woman as well.

And then, on November 1, 1986, a beloved 18-year-old white dry-cleaning clerk by the name of Ronda Morrison was shot numerous times from behind by an unknown assailant.

At the time, Walter McMillian was at a church fish fry, but this didn’t matter to the newly elected and openly racist Sheriff Tom Tate, after Ralph Myers—an illiterate and mentally unstable friend of Karen Kelly—arbitrarily implicated McMillian (Karen’s “black boyfriend”) in this and another murder.

Even though it was obvious that “Walter McMillian had never met Ralph Myers, let alone committed two murders with him,” about half a year after the murder of Ronda Morrison, McMillian was arrested by Sheriff Tom Tate.

“There was no evidence against McMillian,” reminds us Stevenson, “no evidence except that he was an African American man involved in an adulterous interracial affair, which meant he was reckless and possibly dangerous, even if he had no prior criminal history and a good reputation. Maybe that was evidence enough.”

Inventing the Evidence

Well, even if that was evidence enough as far as the Sheriff was concerned, judges usually want a bit more to send a man to the death sentence.

Well, Tom Tate, the District Attorney, and several investigators took care of that: they bribed witnesses, they forced Ralph Myers to testify that McMillian was the murderer even after he had tried to recant, and systematically ignored evidence in favor of Walter.

There were many witnesses (all of them black) who swore, under oath, that at the time of the murder, McMillian was at the church fish fry, but an almost all-white jury (there was only one African American member) pronounced McMillian guilty and recommended a life sentence after a day and a half sham trial.

Why only that, said Judge Robert E. Lee Key, using the “unique Alabama practice” called “Judge Overrule” to override the jury and impose the death penalty.

After all—and this is where things get extraordinarily Kafkaesque—Walter McMillian had already been sent by the Judge to await trial on death row, even before the defense could present its case!

EJI’s Intervention

How do we know all of the above?

Bryan Stevenson and his newly-founded Equal Justice Initiative took on the case and started finding all kinds of dirt connected to it after Ralph Myers revealed to the McMillian’s trial counsel that he had given false testimony against Walter.

That was merely the beginning of the investigation. It would take years for Myers to officially recant the testimony, and the EJI to discover proofs of the bribery methods used by the State to convict Walter and the ways in which their racially motivated hatred had messed with the evidence.

After the case gained nationwide attention as part of the CBS program 60 Minutes, new DA Tom Chapman launched his own investigation which confirmed EJI claims regarding Walter’s innocence.

Because of this, the EJI was in a good position to move for the state to drop all charges against McMillian, and, after six years on death row, Walter McMillian was finally released.

However, by this time, Walter had already changed and, despite the efforts of EJI to help him reenter society, he developed dementia and anxiety probably brought on to him by the trauma of imprisonment.

Walter McMillian died in 2013, on September 11.

The Quality of Mercy: “Above This Sceptred Sway”

At Walter’s funeral, Bryan Stevenson was one of the people asked to give a speech to the congregation.

“I felt the need to explain to people what Walter had taught me,” informs us Stevenson in Just Mercy and goes on to list, so poignantly and so clearly, not all the things he said at Walter’s funeral, but, coincidentally, all the raison d’êtres behind his book:

Walter made me understand why we have to reform a system of criminal justice that continues to treat people better if they are rich and guilty than if they are poor and innocent. A system that denies the poor the legal help they need, that makes wealth and status more important than culpability, must be changed. Walter’s case taught me that fear and anger are a threat to justice; they can infect a community, a state, or a nation and make us blind, irrational, and dangerous. I reflected on how mass imprisonment has littered the national landscape with carceral monuments of reckless and excessive punishment and ravaged communities with our hopeless willingness to condemn and discard the most vulnerable among us. I told the congregation that Walter’s case had taught me that the death penalty is not about whether people deserve to die for the crimes they commit. The real question of capital punishment in this country is, ‘Do we deserve to kill?’

Walter had thought Bryan something even more beautiful and enduring: the quality of mercy.

“Mercy is just when it is rooted in hopefulness and freely given,” writes Stevenson memorably, not only channeling but transcending his inner Portia. “Mercy is most empowering, liberating, and transformative when it is directed at the undeserving. The people who haven’t earned it, who haven’t even sought it, are the most meaningful recipients of our compassion.”

Remember that: just mercy belongs to the undeserving.

And it is the only thing strong enough to “break the cycle of victimization and victimhood, retribution and suffering. It has the power to heal the psychic harm and injuries that lead to aggression and violence, abuse of power, and mass incarceration.”

Key Lessons from “Just Mercy”

1. (Biased) Mass Incarceration Is a Serious (American) Problem

2. Justice Is the Antonym of Poverty

3. Each of Us is More Than the Worst Thing We’ve Ever Done

(Biased) Mass Incarceration Is a Serious (American) Problem

At present, there are 2.3 million people imprisoned in the USA, and thrice that (about six million) are on probation or on parole. That makes for a staggering number of more than 8 million criminals living on US soil, which basically means that if you know more than 40 people, you definitely know at least one criminal.

How does that compare to other countries?

Really, really bad!

With 737 prisoners per 100,000 people, the USA tops the prison rates charts, housing almost a million more prisoners than China, even though China’s population is about four times that of the US.

What’s worse and statistically improbable, a lot of these prisoners are African-Americans!

“One in every fifteen people born in the United States in 2001 is expected to go to jail or prison,” informs us Stevenson, “one in every three black male babies born in this century is expected to be incarcerated.”

Justice Is the Antonym of Poverty

And you know why there are so many imprisoned Americans, especially black?

Because most of them are marginalized in at least one other way, being either too poor or too young to find someone to defend them.

Stevenson writes:

My work with the poor and the incarcerated has persuaded me that the opposite of poverty is not wealth; the opposite of poverty is justice… I’ve come to believe that the true measure of our commitment to justice, the character of our society, our commitment to the rule of law, fairness, and equality cannot be measured by how we treat the rich, the powerful, the privileged, and the respected among us. The true measure of our character is how we treat the poor, the disfavored, the accused, the incarcerated, and the condemned.

Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done

If you need to remember one thing from Bryan Stevenson’s excellent book, remember this: “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”

That’s the vital lesson he learned working closely with death row inmates, most of them marginalized and frozen out from society.

Instead of punishing them twice, Stevenson argues, we need to offer them a second chance.

“Simply punishing the broken—walking away from them or hiding them from sight—only ensures that they remain broken and we do, too,” he concludes. “There is no wholeness outside of our reciprocal humanity.”

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Just Mercy Quotes”

Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done. Share on X The true measure of our character is how we treat the poor, the disfavored, the accused, the incarcerated, and the condemned. Share on X The death penalty is not about whether people deserve to die for the crimes they commit. The real question of capital punishment in this country is, Do we deserve to kill? Share on X Mercy is just when it is rooted in hopefulness and freely given. Mercy is most empowering, liberating, and transformative when it is directed at the undeserving. The people who haven’t earned it, who haven’t even sought it, are the most… Share on X An absence of compassion can corrupt the decency of a community, a state, a nation. Share on XOur Critical Review

“Not since Atticus Finch has a fearless and committed lawyer made such a difference in the American South,” writes everyone’s favorite author of legal thrillers, John Grisham, reviewing Just Mercy.

“Though larger than life,” he goes on, “Atticus exists only in fiction. Bryan Stevenson, however, is very much alive and doing God’s work fighting for the poor, the oppressed, the voiceless, the vulnerable, the outcast, and those with no hope. Just Mercy is his inspiring and powerful story.”

Moving, poignant and searing, Just Mercy is indeed a marvel of a book, and Bryan Stevenson one of the heroes of our age.As Nicholas Kristof, writing for The New York Times wrote, he “may, indeed, be America’s Mandela,” echoing the opinion of none other than one Nobel Peace Prize-winning human rights activist Desmond Tutu.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.