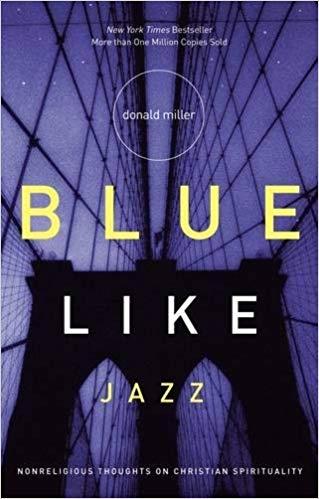

Blue Like Jazz

20 min read ⌚

Nonreligious Thoughts on Christian Spirituality

You’ve probably never met a Christian such as Donald Miller.

After all, his most famous book is subtitled “nonreligious thoughts on Christian spirituality.”

And, even more curiously, it is titled:

Who Should Read “Blue Like Jazz”? And Why?

Well, it is difficult to answer these questions because we feel that, even though written primarily for Christian audience, non-religious readers might find this book much more appealing than Christians; in fact, some Christians may even be offended by Donald Miller’s beliefs.

This book allows us to take a stand on what we believe about Christian culture and conversations with God and helps us critically think through what Christian spirituality really looks like in today’s society.

Read it if you think that faith is necessary, but that institutionalized religion has made it seem unfashionable for our atheist, postmodern times.

About Donald Miller

Donald Miller is an American religious writer, public speaker, and business owner.

Even though he made his name as an unconventional advocate for faith in our times, Miller is now much more sought-after as a brand maker, being the CEO of StoryBrand, a company which helps businesses clarify their missions and messages.

In fact, his last book is titled Building a StoryBrand and is pretty different from the books with which he made his name: Blue Like Jazz, Searching for God Knows What, and A Million Miles in a Thousand Years.

Book Summary

Semi-autobiographical and hugely popular, Donald Miller’s second book, Blue Like Jazz, is basically a collection of essays on the nature of God and Christianity.

There’s a sort of a narrative there since most of these essays chronicle Miller’s personal experiences and the experiences of several of his friends – Mitch, Penny, Laura – all of them students at the liberal arts Reed College in Portland, Oregon, and all of them trying to understand their purpose being here and, consequently, their belief in something larger than human life.

After a more than successful Kickstarter campaign, Blue Like Jazz was adapted into a movie by director Steve Taylor in 2012. If you haven’t watched it yet, here’s a trailer to pique your fancy:

Author’s Note

First of all, let’s get one thing straight: this book barely mentions jazz.

Then, why the title?

Well, it’s the arch metaphor of the book, and it’s kind of difficult to understand it if you skip the author’s note.

We won’t allow that.

Here’s it in full:

I never liked jazz music because jazz music doesn’t resolve. But I was outside the Bagdad Theater in Portland one night when I saw a man playing the saxophone. I stood there for fifteen minutes, and he never opened his eyes.

After that, I liked jazz music.

Sometimes you have to watch somebody love something before you can love it yourself. It is as if they are showing you the way.

I used to not like God because God didn’t resolve. But that was before any of this happened.

So, in a way, Donald Miller says that God is like jazz because neither of them resolves, because neither of them is a well-rounded story with an ending; both of them go on, and go on – and it’s your job to build a relationship toward them.

More importantly, this author’s note implicitly uncovers Donald Miller’s belief that maybe seeing (or, in this case, reading about) his unique kind of love for God may make you love God as well.

Just like he fell in love with jazz after seeing somebody lovingly play it.

Chapter 1 | Beginnings: God on a Dirt Road Walking Toward Me

In the first chapter of Blue Like Jazz, Donald Miller takes us on a guide through selected events from his childhood, all framed with (surprise! surprise!) quite a few daddy issues (his dad left him when he was young).

Consequently, you can understand why for Miller, the concept of Father God was a strange one: it both signified something which he lacked and something of which he had a pretty different understanding than most of the other people.

“When I was introduced to the concept of God as Father,” he writes, “I imagined Him as a stiff, oily man who wanted to move into our house and share a bed with my mother. I can only remember this as a frightful and threatening idea.”

That’s why when he heard an Indian talking about the pantheistic nature of God, he realized the beauty of such a concept: if God was everywhere, he could swim in Him or have Him brush his face in a breeze.

And in a way, that’s what eventually happened.

“Years ago,” writes Miller, God “was a swinging speck in the distance; now He is close enough I can hear His singing. Soon I will see the lines on His face.”

Chapter 2 | Problems: What I Learned on Television

In this chapter, Donald really introduced to us for the first time.

Unlike many other religious people, Donald is just like you, an average Joe.

Meaning: he likes to be cool, he is not that uninterested in science (the chapter begins with his friend’s note that light exists outside of time), he cusses, he drinks, he smokes – and he wants to have sex when given the chance.

Also, he’s not a Republican. In fact, in this chapter we see him joining his friend Andrew the Protester on an anti-Bush rally; they have their reasons.

Further down the chapter, Donald informs us that, in his opinion, Christians are right: we have a sinful nature since it is much easier to do bad things than good ones.

“And there is something in that basic fact,” he concludes in discussion with his friend Tony the Beat Poet, “some little clue to the meaning of the universe.”

Chapter 3 | Magic: The Problem with Romeo

“I couldn’t give myself to Christianity,” writes Miller in chapter 3, “because it was a religion for the intellectually naive. In order to believe Christianity, you either had to reduce enormous theological absurdities into children’s stories or ignore them.”

“The entire thing,” he goes on, “seemed very difficult for my intellect to embrace. Now, none of this was quite defined; it was mostly taking place in my subconscious.”

However, the reason why Miller believed this was watered-down children’s Bibles which think that the essence of religion is the story; during his literature classes at Reed College, Donald Miller realized that it is not.

Or, at least, that this is merely the beginning.

There’s Copperfield saying that nothing is magical, and there’s Copperfield doing a trick nobody can explain. And everybody remains silent and awestruck for a while.

“I had always hated hearing about it because it seemed so entirely unfashionable a thing to believe, but it did explain things,” concludes Miller. “Maybe these unfashionable ideas were pointing at something mystical and true. And, perhaps, I was judging the idea, not by its merit, but by the fashionable or unfashionable delivery of the message.”

Chapter 4 | Shifts: Find a Penny

If you remember well, Reed College is a liberal arts college. And that means, well, read between the lines: drugs, alcohol, atheism – you name it. (“Some of the Christians in Portland talk about Reed College as if it is Hades.”)

It’s highly unfashionable to be a religious person among the artists of today; if not because of something else, but because of the fact that religion bans about 90% of the things artists do.

In Chapter 4, Donald introduces us to two of his closest friends, who, in a way, seem like two very opposite sides of the same coin:

• Laura, the anti-religion “I can do what I want” student who is too smart for her own sake, barely capable of finding a class challenging enough for her intellect; and

• Penny, a devout Christen who believes that God once spoke to her.

Chapter 5 | Faith: Penguin Sex

Well, this one was kind of expected: Laura falls into a severe state of depression.

“Boy stuff?” – Don asks. “No.” “School stuff?” Another “no.” “God stuff.” “I guess so, Don,” she says. Because, we guess, these are the only three reasons one might fall into depression, ha?

Anyway, this whole chapter consists of two attempts to convert Laura into a believer. The first attempt fails: “If God is real, He needs to happen to me,” says Laura to Don, who can’t explain his faith because, well, it is, by definition unexplainable.

“My belief in Jesus did not seem rational or scientific, and yet there was nothing I could do to separate myself from this belief.”

But then, in another discussion, Tony asks Don why he believe at all, and Don starts talking about penguins and their mating rituals.

“They have this radar inside them that told them when and where to go, and none of it made any sense,” he says, “but they show up on the very day their babies are being born, and the radar always turns out to be right. I have a radar inside me that says to believe in Jesus. Somehow, penguin radar leads them perfectly well. Maybe it isn’t so foolish that I follow the radar that is inside of me.”

Of course, this somehow gets to Laura and, after some time, she sends Don a message:

“I read through the book of Matthew this evening,” it says. “I was up all night. I couldn’t stop reading so I read through Mark. This Jesus of yours is either a madman or the Son of God. Somewhere in the middle of Mark, I realized He was the Son of God. I suppose this makes me a Christian. I feel much better now.”

Chapter 6 | Redemption: The Sexy Carrots

“I found myself trying to love the right things without God’s help,” notes Don in this chapter, “and it was impossible.”

“I tried,” he goes on, “to go one week without thinking a negative thought about another human being, and I couldn’t do it. Before I tried that experiment, I thought I was a nice person, but after trying it, I realized I thought bad things about people all day long, and that, like Tony says, my natural desire was to love darkness.”

In a way, nothing helps Don makes sense of his life – or, even better, the ethical structure of the universe – in the absence of Jesus.

Not even rigorous self-discipline.

Chapter 7 | Grace: The Beggars’ Kingdom

“I was a fundamentalist Christian once,” starts chapter 7. “It lasted a summer.”

Why?

Because, in the eyes of Don, self-discipline is almost impossible when there isn’t a goal behind it. It just makes you unhappy. After all, how can you be happy when you’re renouncing all of the worldly pleasures, and there’s no transcendental reason behind it?

It’s difficult even when there is: Don’s pastor Rick, “anguished by an inability to control his desires,” one evening “swallowed enough muscle relaxants and sleeping pills to kill three people.”

He didn’t die, of course, but he understood one important thing: God is not a loan shark, and he doesn’t ask anything in return but purity and humbleness.

“Your life is not your own,” Rick heard God speaking to him at that moment, “but you have been bought with a price.”

Chapter 8 | Gods: Our Tiny Invisible Friends

In this chapter, Don tells the story of a guy named Trendy Christian Writer, who Don believes offends everything sacred in this world because he uses “Islamic verbiage to make himself look spiritual, and yet he really hasn’t researched or subscribed to the faith as it presents itself.”

In other words, he’s using the Koran to make himself trendy and popular, and that, in itself is a reason enough to believe that he’s faking it.

Well, Tony, Don’s friend, states the obvious: just like this Trendy Christian Writer, we are raping our faith as well. We’re believing only to the point it suits us.

“When Tony said that,” Don writes, “it was as if truth came into the room and sat down with us. I felt as though Jesus were gently holding my head so He could work the plank out of my eye. Everything became clear.”

To be more precise, Don “realized in an instant that [he] desired false gods because Jesus wouldn’t jump through [his] hoops, and [he] realized that, like Tony, [his] faith was about image and ego, not about practicing spirituality.”

Chapter 9 | Change: New Starts at Ancient Faith

In chapter 9, Don relates us a sort of a religious experience in the Grand Canyon.

Under the stars, he starts feeling what that Indian from the first chapter talks about and he starts talking to God:

“I’m sorry, God,” he shouts to the sky. “I’m sorry I got so confused about You, got so fake. I hope it’s not too late anymore. I don’t really know who I am, who You are, or what faith looks like. But if You want to talk, I’m here now.”

By the end of the evening, Don realizes something profound:

I see it now. I see that God was reaching out to Penny in the dorm room in France, and I see that the racism Laura and I talked about grows from the anarchy seed, the seed of the evil one. I could see Satan lashing out on the earth like a madman, setting tribes against each other in Rwanda, whispering in men’s ears in the Congo so that they rape rather than defend their women. Satan is at work in the cults of the Third World, the economic chaos in Argentina, and the corporate-driven greed of American corporate executives. I lay there under the stars and thought of what a great responsibility it is to be human. I am a human because God made me. I experience suffering and temptation because mankind chose to follow Satan. God is reaching out to me to rescue me. I am learning to trust Him, learning to live by His precepts that I might be preserved.

Chapter 10 | Belief: The Birth of Cool

“My most recent faith struggle,” writes Don at the beginning of his chapter, basically making the main point of the book, “is not one of intellect.”

In other words, he doesn’t think that there’s any point in discussing whether God exists or not. There are some guys who believe that he doesn’t and, moreover, believe that they can prove that he doesn’t; there are also other guys who believe the opposite.

As far as Don is concerned, it really doesn’t matter one bit: “the argument stopped being about God a long time ago, and now it’s about who is smarter, and honestly I don’t care.”

Why?

Because, as Schopenhauer said criticizing Kant’s ethics, we rarely do things for intellectual reasons; most of the time, we do them for emotional.

“If I walk away from Him,” Don writes, “and please pray that I never do, I will walk away for social reasons, identity reasons, deep emotional reasons, the same reasons that any of us do anything.”

Hence, you can be religious even if your outward appearance doesn’t show this; the question of belief is a deeper, more emotional, and more universal question than the question of coolness.

Chapter 11 | Confession: Coming Out of the Closet

Each year at Reed there’s a festival called Ren Fayre – an excuse for getting drunk, getting high, and, we guess, getting laid.

For some reason, Don and other Christens at the college decided that this festival is the best place for them to come out of the closet and confess their faith to others.

How?

By confessing the sins of God, Jesus, and the Church to the non-believers around.

Get it?

It’s the world turned upside-down.

And from the confessional, when asked by another non-religious student named Jake whether he really believes in Jesus, Don says it out loud: “Yes, I think I do. I have doubts at times, but mostly I do.”

“So many years before I had made amends to God,” concludes Don, “I had made amends to the world. I was somebody who was willing to share my faith. It felt kind of cool, kind of different. It was very relieving.”

Chapter 12 | Church: How I Go Without Getting Angry

“The church is a hospital for sinners,” wrote once Abigail Van Buren, “not a museum for saints.” As a review of Blue Like Jazz notes, Miller, in a way doesn’t believe either.

To him, a church should be understood the very way Jesus described it: wherever two people are talking about him.

In fact, he ends this chapter by offering a three-step formula on how to find a church where you can go to without getting angry about the values it fails to represent nowadays:

• Pray that God will show you a church filled with people who share your interests and values;

• Go to the church God shows you;

• Don’t hold grudges against any other churches. God loves

Sounds easy enough, ha?

Chapter 13 | Romance: Meeting Girls Is Easy

The highlight of this chapter is a few-page-long quote from Polaroid, a play by Donald Miller himself, “the story of one man’s life from birth to death, each scene delivered through a monologue with other actors silently acting out parts behind the narrator as he walks the audience through his life journey.”

In it, the husband whispers to his sleeping wife words of love which sound romantic, but which also include just too much of God and biblical references to be poignant.

Chapter 14 | Alone: Fifty-Three Years in Space

In this chapter, Miller reveals both his loneliness and how he used to think that being in love with someone is the only cure for it.

Nowadays, he doesn’t seem to believe that love is the opposite of loneliness, but merely an opposite, because he knows full well from the many moments passed in solitude that, when alone, a man craves for many things, a romantic partner being merely one of them.

“I think our society puts too much pressure on romantic love,” he writes, “and that is why so many romances fail. Romance can’t possibly carry all that we want it to.”

We believe Donald’s right.

There are also a few quite interesting paragraphs in this chapter dedicated to Donald Miller’s appreciation of Emily Dickinson’s poetry.

Now, that’s a long-lasting crash of Don’s.

“I don’t care why we get crushes on Emily Dickinson,” he writes. “It is a rite of passage for any thinking man. Any thinking American man.”

Chapter 15 | Community: Living with Freaks

Have you ever watched Dan Harmon’s Community (which, by the way, was amazing)?

If so, then you can guess what this chapter is all about: Donald moves in with some other guys and realizes why his pastor, Rick, doesn’t believe that faith is something you do alone.

In fact, Rick is the one who suggests that Don should live in a community: solitude is not something a man should experience, he thinks, you know, being a social being and all.

Of course, there are plenty of unplanned events and mishaps when you’re living in a community, but, in the end, it’s worth it.

Just like in marriage: you lose some freedom in the short term, but that’s the only way to earn that coveted victory lap after all is said and done.

Chapter 16 | Money: Thoughts on Paying Rent

You’ll understand why we have to quote the beginning of this chapter in full:

Writers don’t make any money at all. We make about a dollar. It is terrible. But then again, we don’t work either. We sit around in our underwear until noon then go downstairs and make coffee, fry some eggs, read the paper, read part of a book, smell the book, wonder if perhaps we ourselves should work on our book, smell the book again, throw the book across the room because we are quite jealous that any other person wrote a book, feel terribly guilty about throwing the schmuck’s book across the room because we secretly wonder if God in heaven noticed our evil jealousy, or worse, our laziness. We then lie across the couch facedown and mumble to God to forgive us because we are secretly afraid He is going to dry up all our words because we envied another man’s stupid words. And for this, as I said, we are paid a dollar. We are worth so much more.

“I hate not having money,” goes on Donald Miller. “I hate not being able to go to a movie or out for coffee. I hate that feeling at the ATM when, after getting cash, the little receipt spits out, the one with the number on it, the telling number, the ever-low number that translates into how many days I have left to feel comfortable.”

A successful book and a movie later, we kind of guess that Donald’s quite better now. For one, we don’t think that the number on that receipt is low now.

Chapter 17 | Worship: The Mystical Wonder

“There are many ideas within Christian spirituality that contradict the facts of reality as I understand them,” writes Don tellingly.

Now, he’s pretty aware that “a statement like this offends some Christians,” but he stands by it: “There are all sorts of things our hearts believe that don’t make any sense to our heads,” he goes on. “Love, for instance; we believe in love. Beauty. Jesus as God.”

Donald says that he doesn’t believe that one can be a true Christian without being a mystic. Just like Wittgenstein implies in the Tractatus (6.522), belief is something beyond our grasp of reality, something inexpressible, something downright mystical.

As far as Don is concerned, even if our theology is wrong (as it seems to him that it is), he firmly believes that God has everything figured out.

And he respects this in wonder.

Because, he concludes, “wonder is that feeling we get when we let go of our silly answers, our mapped out rules that we want God to follow. I don’t think there is any better worship than wonder.”

Chapter 18 | Love: How to Really Love Other People

To our eyes, this is one of the most interesting chapters in the book. In it, Don reveals how living with a bunch of hippies during one summer taught him the real difference between being good and bad.

Surprise, surprise – it has nothing to do with how you proclaim your faith to others; it has everything to do with how you practice it.

You see, there are many people who go to church and dub themselves Christians, but who are, deep down in them, bigots, racists, sexists, and would want to build a wall to keep Mexicans far from the USA.

We’re not putting words into Donald’s mouth: he really understands why liberals don’t like Republicans.

The real issue in the Christian community, he says, is its conditionality.

Simply put, if you are with us, we like you. However, if you have questions – “questions about whether the Bible was true or whether America was a good country or whether last week’s sermon was good” – you are not so loved.

Even worse, you are loved only in words, but not in practice.

“By toeing the party line you earned social dollars,” Donald writes, “by being yourself you did not. If you wanted to be valued, you became a clone.”

Now, how is that relevant to Donald living with hippies for a summer?

Well, he never felt more alive than at that time. And he never felt more loved or loving. These people didn’t judge anyone because of their beliefs; even though non-religious, they were far more practicing in what the Bible states than preaching Christians.

A hippie would have no problems talking about everything with a Christian; a Christian, on the other hand, would have all sorts of problems even with a hippie living two houses from him.

Now, who’s the real Christian there?

Chapter 19 | Love: How to Really Love Yourself

Now that we’ve learned how to really love other people, it’s time to learn how to really love ourselves.

As far as Don was concerned, this was not an option: as we already explained above, the only way to accept Jesus is by being humble, and loving yourself seems to have arrogance written all over it.

However, after going to a therapist on account of his romantic troubles, Don realizes that the only alternative to loving yourself is hating yourself.

In other words, you do not love yourself merely because of you; you love yourself because of those around you. Only the ones who truly love themselves can love others, and only the ones who love others are accepted by God.

So, there it is: a great apology for being a narcissist.

Chapter 20 | Jesus: The Lines on His Face

Well, it’s safe to say that in this chapter you’ll encounter one of the most blasphemous sentences ever written by a preaching/acting Christian: “Sometimes I picture this Osama Bin Laden-looking Jesus talking with His friends around a fire…”

We may be ignorant, but we don’t remember ever reading someone comparing Jesus to Osama Bin Laden.

And yet – all you, offended Christian, shut your ears – this is a fairly correct assessment, in the “Charlie Chaplin looks like Hitler” sense.

The problem?

After reading this sentence, we can’t seem to think of Osama without thinking of Jesus and vice versa. Hopefully, it will pass.

Anyway, in this last chapter, Donald returns once again to the introductory jazz/God comparison and expands it to include Christianity.

And this is a beautiful comparison to end our summary with:

I think Christian spirituality is like jazz music. I think loving Jesus is something you feel. I think it is something very difficult to get on paper. But it is no less real, no less meaningful, no less beautiful.

The first generation out of slavery invented jazz music. It is a music birthed out of freedom. And that is the closest thing I know to Christian spirituality. A music birthed out of freedom. Everybody sings their song the way they feel it, everybody closes their eyes and lifts up their hands.

Key Lessons from “Blue Like Jazz”

1. Jesus Is Something You Should Experience, Not Something You Can Know

2. A Church Is a Place Where People Share Your Interests and Values

3. You Love Yourself So That You Can Love Others

Jesus Is Something You Should Experience, Not Something You Can Know

There’s no point in looking for a scientific explanation of God; even if it exists, it is, in a way, the antidote to the nature of belief.

We believe because of some inner radar that works the same way the inner radars of penguins do: somehow, they know exactly what they should do to save the lives of their unborn children, and yet they never communicate it.

Well, this is what faith looks like.

It is about wonder, not about science.

A Church Is a Place Where People Share Your Interests and Values

Consequently, Donald Miller wouldn’t blame you if you don’t like going to church. Many of the people there are simply not good people: they act as if they are religious but deep in their hearts, they are not.

The best way to really start loving going to church is to find a church filled with people who share your interests and values.

And they don’t even have to be Christians: Donald Miller had one such experience with liberal booze-loving drug-using hippies.

You Love Yourself So That You Can Love Others

In order to love God, and let Him in your heart, you need to be humble; and yet, in order to be humble, you need to first learn to love yourself.

It is a bit of a paradox, but it makes sense.

Because the only alternative to loving yourself is hating yourself; and people who hate themselves are bitter and can’t love other people, let alone God.

Just think of it this way: you’ll help more people during a plane crash if you put your protection mask first and then start doing this for those around you.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Blue Like Jazz Quotes”

Believing in God is as much like falling in love as it is making a decision. Love is both something that happens to you and something you decide upon. Share on X Sometimes you have to watch somebody love something before you can love it yourself. Share on X Dying for something is easy because it is associated with glory. Living for something is the hard thing. Living for something extends beyond fashion, glory, or recognition. We live for what we believe. Share on X I always thought the Bible was more of a salad thing, you know, but it isn't. It's a chocolate thing. Share on X The most difficult lie I have ever contended with is this: life is a story about me. Share on XOur Critical Review

Blue Like Jazz is a curious book: it may seem too unchristian to Christians, and too cool for a Christian to atheists.

But that’s exactly why you should read this book, regardless of your starting position.

Even if it does nothing else for you, it will certainly make you think.

Christian or non-Christian.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.