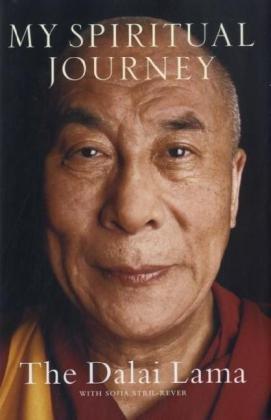

My Spiritual Journey Summary

12 min read ⌚

Want to learn more about the life and philosophy Dalai Lama?

Here’s one of the best books to do so:

Who Should Read “My Spiritual Journey”? And Why?

The 14th Dalai Lama—aka Tenzin Gyatso—has authored or co-authored almost a hundred books, but My Spiritual Journey is one of the best-structured ones if you want to learn more about him and his worldview.

No wonder it was originally Mon autobiographie spirituelle, which is French for My Spiritual Autobiography. Though indisputably unconventional one, at times it does read like that—and is certainly the closest thing you can find on the market to an autobiography of Dalai Lama.

Kudos to Sofia Stril-Rever—a renowned Sanskrit expert and an interpreter for the Dalai Lama for more than a decade and a half—who managed to compile the book, and provide it with sometimes necessary footnotes and annotations.

About Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama is the title Tibetans give to their foremost spiritual leaders. The current one is the last in a line of fourteen Dalai Lamas, and his religious name is Tenzin Gyatso.

Enthroned as the Dalai Lama in 1940, and assuming political duties a decade later (at the tender age of 15), Tenzin Gyatso is consensually considered one of the spiritual leaders of the world.

Consulted on various questions, the Dalai Lama has authored and co-authored many books, most of which are translated into several languages. Among them are The Art of Happiness and The Book of Joy, the latter one co-authored with Desmond Tutu.

For his dedication to the cause of Tibet and his belief in nonviolence as the only path to a better future for humanity, the current Dalai Lama won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989 and was dubbed one of the “Children of Mahatma Gandhi” by TIME magazine.

“My Spiritual Journey Summary”

When it first appeared in French, the original title of My Spiritual Journey was My Spiritual Autobiography. It was only for the English edition that the book got another title, one which tries to acknowledge the enormous contribution of Dalai Lama’s translator and the compiler of this book, Sofia Stril-Rever.

The clarification, however—as the editor of the English edition says—”should in no way be perceived as anything but an authentication of these inspiring stories, lessons, and spiritual truths as the Dalai Lama’s own, and an accurate and approved presentation of his spiritual journey through a most remarkable life.”

Dalai Lama’s Three Commitments to Life

My Spiritual Journey consists of three parts, each of which chronicles the Dalai Lama’s spiritual journey in one of three ways: as a human being, as a Buddhist monk, and as the Dalai Lama.

The book is framed the way it is because of the impact a speech of the Dalai Lama had on Sofia Stril-Rever. The speech was originally delivered by the Dalai Lama to the European Parliament in Brussels, on December 4, 2008, and it is reprinted in the book as more than just a suitable afterword.

We’ll summarize it here first because it seems like the best way to start the summary. In the speech, the Dalai Lama lists the three commitments in his life.

The First Commitment, as a Human Being

Dalai Lama’s first commitment, as a human being, is “the promotion of human values and those qualities of spirit that are key elements in a happy life, whether of an individual, a family, or a community.”

According to him, these days, very few people seem to cultivate these values and qualities—which is why he thinks it is his priority to advocate them.

The Second Commitment, as a Buddhist Monk

Dalai Lama’s second commitment, now as a Buddhist monk, is “the promotion of harmony among the different religions.” At first, this may sound a bit strange, because, let’s face it, the objective of most religions is to prove that theirs is the only valid one.

The Dalai Lama, fortunately, is one who understands the concept of holy envy and, moreover, one who has a real understanding of the difference between being religious and being spiritual (as we explained above).

Nobody would ever doubt the necessity of pluralism in political life—that is the essence of democracy, isn’t it?—and yet, people are not that confident when it’s a matter of diversity of beliefs and religions.

Well, the Dalai Lama can’t see the logic behind this, especially in view of the fact that “all the chief religious traditions bring us the same message of love, compassion, tolerance, temperance, and self-discipline.”

The Third Commitment, as the Dalai Lama

Almost expectedly, Dalai Lama’s third commitment—as the Dalai Lama—is the cause of Tibet.

People often forget that, despite being one of the spiritual leaders of the world, he is also a political leader of a country. Moreover, a country that is basically occupied by one of the two superpowers, China.

The Dalai Lama has been in exile ever since 1959—he lives in India—but he has never forgotten the well-being of his people.

He is aware that unlike his first two commitments (which depend solely on his will and discipline), the third one will only come to an end when a mutually satisfying solution is found between the Tibetans and the Chinese.

It’s sad to say this, but it seems like the Dalai Lama has given up hope that this will happen in his lifetime.

Part One: As a Human Being

The first part of My Spiritual Journey encompasses two chapters: “Our Common Humanity” and “My Lives Without Beginning or End.” In them, the Dalai Lama explains not only his childhood and upbringing in Lhasa but also his philosophy and worldview.

Our Life Depends on Others

The basis of Dalai Lama’s personal beliefs is quite simple:

No matter what part of the world we come from, fundamentally we are all the same human beings. We all seek happiness and want to avoid suffering. We all have essentially the same needs and similar concerns. As human beings, we all want to be free, to have the right to decide our own destiny as individuals as well as the destiny of our people. That is human nature.

This is something the Dalai Lama believes quite unwaveringly. As he sees it, his title “Dalai Lama” is just a responsibility that has come down to him and nothing else. On his basis, he is just a normal human being—it just so happens that he is also a Buddhist and a Tibetan.

This view, of course, has far-reaching consequences.

For one, it blows in the face of the radical individualism the 21st century is infested with. Unlike most ideologists of today, the Dalai Lama doesn’t think that “the meaning of life” is a question that can be answered on an individual basis.

He is quite confident in the opposite, in fact.

“Our life depends on others so much,” he writes, “that at the root of our existence, there is a fundamental need for love. That is why it is good to cultivate an authentic sense of our responsibility and a sincere concern for the welfare of others.”

In other words, if all human beings long for love, how can we expect that glorifying individualism can prepare the way for a better, happier twenty-first century?

“Until My Last Breath, I Will Practice Compassion”

It is only through the acknowledgment that we are all alike and that each of us has a need for the other that we can really put back the capital H at the beginning of the word “humanity.”

This acknowledgment has a name.

It is compassion:

True compassion does not stem from the pleasure of feeling close to one person or another, but from the conviction that other people are just like me and want not to suffer but to be happy, and from a commitment to help them overcome what causes them to suffer… This attitude is not limited to the circle of our relatives and friends. It must extend to our enemies too. True compassion is impartial and bears with it a feeling of responsibility for the welfare and happiness of others. True compassion brings with it the appeasement of internal tensions, a state of calmness and serenity. It turns out to be very useful in daily life when we’re faced with situations that require self-confidence. And a compassionate person creates a warm, relaxed atmosphere of welcome and understanding around him. In human relations, compassion contributes to promoting peace and harmony.

The Dalai Lama thinks of himself as “a devoted servant of compassion”: he says that nothing gives him more satisfaction than the practice of empathy and kindness.

When he left Tibet, he often says, he left all his wealth and material belongings behind him. But in his heart, he did manage to take with him something priceless: infinite compassion.

Another thing he didn’t forget to take with him: contagious laughter. He says that he smiles all the time and that he has always tried to laugh away the worries and anxieties.

How does he have the strength?

Well, to quote him, he says that he is “a professional laugher.” And we don’t even know if he’s joking or not!

Part Two: As a Buddhist Monk

In the second part of the book—consisting of three chapters (“Transforming Oneself,” “Transforming the World,” and “Taking Care of the World”), the Dalai Lama explores his experiences as a Buddhist monk.

He introduces us to his ideal, that of the Bodhisattva, and talks about the necessity of pluralism when it comes to religion.

One part that really struck a chord with us was the Dalai Lama’s attempt to differentiate between religion and spirituality:

It seems important to me to distinguish between religion and spirituality. Religion implies a system of beliefs based on metaphysical foundations, along with the teaching of dogmas, rituals, or prayers. Spirituality, however, corresponds to the development of human qualities such as love, compassion, patience, tolerance, forgiveness, or a sense of responsibility. These inner qualities, which are a source of happiness for oneself and for others, are independent of any religion. That is why I have sometimes stated that one can do without religion, but not without spirituality. And an altruistic motivation is the unifying element of the qualities that I define as spiritual.

This is why, the Dalai Lama calls for a spiritual and ethical revolution, one that will blur the lines between this and that and transform the world in our lifetimes.

He, once again, points the finger in the direction of the Western societies, which, though amazing in their energy, creativity, and hunger for knowledge, are disregarding interdependence as a fact of both nature and life.

“Even the smallest insects,” the Dalai Lama says, “are social beings who, without the slightest religion, law, or education, survive thanks to mutual cooperation, based on an innate recognition of their interrelatedness.”

And if “the myriad forms of life, as well as the subtlest levels of material phenomena, are governed by interdependence,” then why should humans be any different?

Buddha discovered this millennia ago; and, for some reason, we still refuse to take note.

Part Three: As the Dalai Lama

The last section of My Spiritual Journey is, expectedly, the most political one.

It relays, in two chapters (“In 1959 the Dalai Lama Meets the World” and “I Appeal to All the Peoples of the World”) his story as the political leader of a stateless nation.

We learn how the Dalai Lama became the temporal leader of Tibet at the age of 16, and how, from that moment on, he became the target of Chinese interest.

Just one year before the Dalai Lama assumed full political duties, Mao Tse-tung had proclaimed the birth of the People’s Republic of China, and very soon made known his intention to “liberate” Tibet.

On October 7, 1950, 40,000 men from the People’s Liberation Army of China crossed the river Yangtze (the eastern border between Tibet and China) and entered the country of the Dalai Lama

8,500 Tibetan soldiers could do nothing: the Chinese troops stopped just a little short of Tibet’s capital, Lhasa, and asked the Tibetan government to send a delegation to Beijing to negotiate the condition of the “peaceful liberation.”

The next year, a Seventeen Point Agreement was reached which affirmed Chinese sovereignty over Tibet. But on March 10, 1959, a revolt erupted in Lhasa, which was put down by the Chinese at the cost of much bloodshed.

Dalai Lama’s life was in danger, but thousands of Tibetans spontaneously created a wall with their bodies around his summer residence and didn’t disperse for a week. Eventually, most of them were killed by the Chinese Red Army.

But by then, masked as an ordinary soldier, the Dalai Lama had fled Tibet under the protection of the Freedom Fighters.

He settled in India, from where he is still loud in his support for Tibet, appealing to the people of the world for help.

“I Place My Hope in the Human Heart”

“In spite of the atrocious crimes the Chinese have committed in our country,” writes the Dalai Lama in the paragraphs chosen by Stril-Rever to serve as a sort of conclusion, “I have absolutely no hatred in my heart for the Chinese people.”

Why?

Because, as the Dalai Lama says a little below this sentence, he believes that one of the greatest dangers of the present age is “to blame nations for the crimes of individuals.”

That does a disservice to everyone!

Just think about that!

Whenever you say something along the lines of “The French suck” or “Americans are bad,” you are insulting many admirable French and American citizens. The Dalai Lama says that: he knows many admirable Chinese as well, and it’s wrong to blame the Chinese for his misfortunes and the misfortunes of his people.

It’s not even a matter of “good people vs. bad people;” it’s merely a matter of people who have hope and are sources of it and people who don’t have hope and diminish other people’s hope. The latter ones are the ones that make the mistakes.

Don’t be one of them: “Be a source of hope,” says the Dalai Lama.

That’s precisely what he said to Ron Whitehead, an American poet, in a few sentences which the latter turned into a poem.

“Whatever happens,” its verses say, “never lose hope!… Be a source of compassion, not just for your friends, but for everyone. And whatever happens, whatever happens around you—never lose hope!”

These three words (the refrain of the poem) became a slogan taken up by the Tibetan youth. Nowadays, you can find them on Tibetan T-shirts and inscribed on houses in children’s villages.

Find them in your heart as well.

Key Lessons from “My Spiritual Journey”

1. Only Compassion Has the Power to Save Humanity

2. Eliminate These Three Mental Poisons to Become a Better Person

3. Dalai Lama’s Three Commitments in Life

Only Compassion Has the Power to Save Humanity

According to the Dalai Lama, in the most profound way imaginable, we are all the same—even if reality incessantly attempts to demonstrate the opposite.

It is from here that the most beautiful human trait must arise: compassion. Nothing is as powerful as it. Compassion is born the moment you realize that everyone on this planet—including the people you hate—wants to be happy, and none of us ever wants to suffer.

Remind yourself that as often as you can and the world will be a better place.

Eliminate These Three Mental Poisons to Become a Better Person

According to Buddhist philosophy, there are three mental poisons you should be aware of ignorance, desire, and hatred.

Every time your mind is stung by either one of them, your body starts functioning in ways contrary to those that helped humans live in societies and made them by far the most developed species in the history of the universe.

You need to be mindful of these three poisons: just identifying them is enough to prevent them from taking hold of your mind and body.

So, every time you realize that you don’t know or desire something, or that you hate someone, stop for a second, put that down on paper, and think it through.

Would you like to live in a world ruled by ignorance and hate, a world where instead of wanting to be more, people want to have more?

We neither.

Dalai Lama’s Three Commitments to Life

As a human being, the Dalai Lama is committed to the idea of promoting human values.

As a Buddhist monk, he is interested in promoting harmony between different religions.

Finally, as the 14th Dalai Lama, he wants to see Tibet free.

These are the Dalai Lama’s three commitments in life—and he intends to maintain them until his final breath.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“My Spiritual Journey Quotes”

Historically, the East was more concerned with understanding the mind and the West was more involved in understanding matter. Share on X You must understand that even if your adversaries seem to be harming you, in the end, their destructive activity will turn against them. Share on X We must realize that when basic needs have been met, human development is primarily about being more, not having more. Share on X Human beings are children of the Earth. Whereas our common Mother Earth has tolerated our conduct up to now, she is showing us at present that we have reached the limits of what is tolerable. Share on X We are part of the world as much as the world is part of us. Share on XOur Critical Review

Just like most of the Dalai Lama’s books, My Spiritual Journey is a collection of his speeches and words given at many different occasions and to many different people. Unlike them, this one focuses on his spiritual growth, which is why even its original title, My Spiritual Autobiography, doesn’t seem too far-fetched.It’s simple, informative, and inspiring. And just like Daniel Goleman’s A Force for Good: The Dalai Lama’s Vision for Our World, it offers a penetrating glimpse into the mind of one of the most respected spiritual leaders of today’s world.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.