Things Fall Apart Summary

8 min read ⌚

“There is no story that is not true… The world has no end, and what is good among one people is an abomination with others,” writes Chinua Achebe in “Things Fall Apart.”

And he goes on to retell the true story of Africa – through the eyes of the Africans.

Read it with us!

Who Should Read “Things Fall Apart”? And Why?

We constantly speak of democracy and uniting humanity through diversity, but it seems we’re still slaves to those appealing, but treacherous single stories.

Which makes reading “Things Fall Apart” a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, it is by far the most analyzed and well-known African novel, the one embodying the African identity best. On the other, it is also – unfortunately – the only book written by a black African novelist that has gained an international reputation.

Sold in over 20 million copies worldwide and already a part of many high-school and university curricula, “Things Fall Apart” is a must-read for anyone who wants to learn “the African story” through the words of the Africans.

However, remember that this book should be merely the beginning of your journey of discovery of the Other.

And what a beginning!

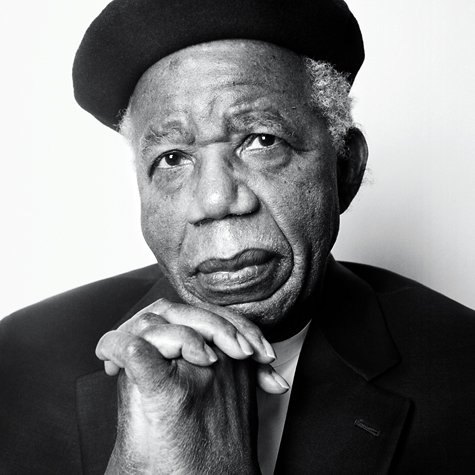

Chinua Achebe Biography

Chinua Achebe was a Nigerian novelist, poet, and professor, widely considered the most influential African writer in history.

was a Nigerian novelist, poet, and professor, widely considered the most influential African writer in history.

He debuted with “Things Fall Apart,” which brought him instant fame and is generally considered his magnum opus. “No Longer at Ease,” “Arrow of God,” “A Man of the People,” and “Anthills of the Savannah” followed, but even though the last one was a Man Booker finalist, none replicated the success of “Things Fall Apart.”

In 2007, Achebe won the Man Booker International Prize. The jury hailed him as “the father of modern African literature,” who “illuminated the path for writers worldwide seeking new words and forms for new realities and societies.”

Achebe died on 21 March 2013 in Boston, U.S.

Plot

Meet Okonkwo, the protagonist of our novel.

He is a strong and hard-working husband of three wives and father of ten children. He is also a leader of his Umuofian clan, specifically respected in his village Iguedo as a local wrestling champion.

Now, if you try looking up Umuofia or Iguedo in a historical dictionary or on a map – the name that will come up will probably be Achebe’s.

Just like Harper Lee’s Maycomb or Fitzgerald’s West Egg – Iguedo is a fictional place, and Umuofia, is a fictional clan.

This doesn’t mean that they don’t have real-world counterparts; but it does mean that they are composites, archetypal structures designed by Achebe to tell more about the real world than the real world itself.

However, if you want to, you can read Nigerians – or, even better, Igbo – every time we mention Umuofians; and Ogidi, Achebe’s birthplace, instead of Iguedo.

Anyway, his reputation aside, Okonkwo isn’t that much of a good guy.

He regularly beats his wife and children and, fixed on the idea of machoism, he’s not interested in any compromise, frequently quarreling with his neighbors.

In an oft-quoted passage, Achebe goes to the bottom of this behavior:

Perhaps down in his heart Okonkwo was not a cruel man. But his whole life was dominated by fear, the fear of failure and of weakness.

It was deeper and more intimate that the fear of evil and capricious gods and of magic, the fear of the forest, and of the forces of nature, malevolent, red in tooth and claw.

Okonkwo’s fear was greater than these. It was not external but lay deep within himself. It was the fear of himself, lest he should be found to resemble his father.

So, just as it often happens in life, the one who shows the least weakness is the one who is most troubled.

In the case of Okonkwo, what’s troubling him is the legacy his father Unoka had left behind him.

Contrary to the Igbo ideal of masculinity, Unoka was weak and tender, preferring his flute to the knife and fainting at the sight of blood. He was also lazy and miserly and left his family in debt.

“And so,” writes Achebe, “Okonkwo was ruled by one passion – to hate everything that his father Unoka had loved.”

And, to a certain extent, being his father’s polar opposite works for Okonkwo. As a hard-working farmer, brave and never shying away from a challenge, he manages to acquire both wealth and the respect of the Umuofians.

However, he also grows to become a rather violent and confrontational man, hating everything even remotely considered as “soft,” such as music, conversations or, you know, emotions in general.

Okonkwo’s life is abruptly changed when he is chosen by his community to adopt a boy from another clan.

Ikemefuna – that is the boy’s name – is, in fact, part of a peace settlement, which should resolve the murder of an Umuofian woman by Ikemefuna’s father.

In time, Okonkwo grows very fond of his adopted son. In fact, he starts loving him more than his biological son Nwoye, whom he believes to be weak.

Naturally, Okonkwo doesn’t show his love for Ikemefuna publicly.

And he does nothing of this sort even when, three years later, the tribe decides that Ikemefuna must die. (Blame it on the Oracle of Umuofia!)

On the contrary, in fact!

He is the one who strikes the final blow, even as Ikemefuna begs his father for his life and protection.

In the meantime, Ogbuefi Ezeudu, one of the Umuofian elders, dies.

At his funeral, during a gun salute, Okonkwo accidentally kills his son, so he and his family are banished for seven years.

That’s how they appeased the gods in those days.

So, Okonkwo goes to Mbanta, his mother’s homeland.

There he learns that the white missionaries have come to Umuofia to introduce their religion (Christianity) and their ways of life.

Mr. Brown, the first missionary, is somewhat accommodating and tries to respect Igbo traditions. However, Mr. Brown is succeeded by Reverend Smith, who is more rigid and uncompromising, leading to increased tensions.

As time passes, more and more people convert to Christianity. And Okonkwo is less and less happy about it.

The straw that breaks the camel’s back is the day his son Nwoye becomes Isaac.

Okonkwo, expectedly, disowns his son.

The seven years pass, and he goes back to his village to find it irretrievably changed by the white newcomers.

Things Fall Apart Epilogue

Things go from bad to worse when a convert unmasks an elder disguised as the Umuofian ancestral spirit – a sacrilegious act.

So, the Umuofians burn a Christian church, and, in return, the whites imprison several Igbo leaders. The Umuofians get their leaders back after paying a hefty ransom but believe that the whites have humiliated them just about enough.

So, they hold a war council, the star of which is, unsurprisingly, Okonkwo.

For him, there’s only one way out – aggressive retaliation. And he shows the way when two court messengers arrive to stop the meeting, beheading one of them.

However, the crowd lets the other one.

Realizing that his opinion is the unpopular one and that the Umuofians will not fight against the white colonizers, Okonkwo hangs himself.

Since, just as in Christianity, suicide is strictly forbidden according to the Igbo teachings, Okonkwo permanently tarnishes his reputation.

And, ironically, after so much effort, he leaves the world the same way his father had before him: in despair and shame.

And so, as the story of Okonkwo’s tragic demise unfolds, we witness the clash of cultures and the devastating consequences of colonialism. Chinua Achebe’s poignant narrative serves as a powerful reminder of the complexities of human existence and the enduring struggle for identity in the face of external forces.

As we reflect on Okonkwo’s fate, we are compelled to consider the broader implications of historical narratives and the importance of recognizing and honoring diverse perspectives in our collective understanding of the past.

In the end, “Things Fall Apart” stands not only as a masterpiece of African literature but also as a profound exploration of the human condition and the perpetual quest for meaning and belonging.

Obierika, Okonkwo’s best friend, sees so much injustice in this: “That man was one of the greatest men in Umuofia,” he shouts to the District Commissioner. “You drove him to kill himself, and now he will be buried like a dog…”

Of course, the District Commissioner couldn’t care less about this.

In his mind, he’s too busy contemplating whether Okonkwo’s story is interesting enough to be granted a chapter or merely a paragraph in the book he’s writing at the moment.

Its title?

“The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger.”

Now, isn’t that nice!

Cultural Collision and Colonial Legacy in Things Fall Apart

In ‘Things Fall Apart,’ Chinua Achebe vividly portrays the clash between Igbo tradition and European colonialism through the life of Okonkwo, a proud leader in the village of Umuofia.

The arrival of Christian missionaries, spearheaded by the benevolent Mr. Brown and later the zealous Reverend James Smith, marks a pivotal turning point.

While Mr. Brown adopts a more tolerant approach, Reverend Smith’s rigid beliefs provoke tension and division within the community.

The missionaries’ influence accelerates as more villagers, including Okonkwo’s own son, convert to Christianity, challenging traditional Igbo beliefs centered around the Earth Goddess, Ani, and the rituals of the village elders.

The symbolic significance of the Evil Forest, where societal outcasts are banished, underscores Achebe’s critique of colonial perceptions of Igbo culture as ‘primitive.’

As Okonkwo grapples with personal tragedy and the erosion of his clan’s autonomy, ‘Things Fall Apart’ powerfully exposes the complexities of cultural identity amidst external pressures.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app, for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Things Fall Apart Quotes”

The white man is very clever. He came quietly and peaceably with his religion… Now he has won our brothers, and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart. Share on X There is no story that is not true… The world has no end, and what is good among one people is an abomination with others. Share on X Among the Igbo the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm-oil with which words are eaten. Share on X ’You do not know me,’ said Tortoise. ‘I am a changed man. I have learned that a man who makes trouble for others makes trouble for himself.’ Share on X When a man is at peace with his gods and ancestors, his harvest will be good or bad according to the strength of his arm. Share on XOur Critical Review

With “Things Fall Apart,” Chinua Achebe gave voice to the African continent back in 1958, using and bending the language of the colonizers to tell the story of the colonized.

Through it, the European and American readers were able – for the first time – to learn comprehensively the way of life of pre-colonial Africans; and the shattering effects the Scramble for Africa had on the continent and its inhabitants.

Half a century later, “Encyclopedia Britannica” included it in its list of “12 Novels Considered the Greatest Book Ever Written.”

And we certainly won’t argue the decision.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.