Discipline and Punish Summary

8 min read ⌚

The Birth of the Prison

The Birth of the Prison

Have you ever wondered why public tortures and executions evolved into prisons and penitentiaries?

Steven Pinker would say because of the better angels of our nature.

Michel Foucault, in “Discipline and Punish” claims that, unfortunately, it’s because of the worse – If not the devils.

Who Should Read “Discipline and Punish”? And Why?

“Discipline and Punish” is an extremely work of philosophy and sociology and anyone who’s interested in either should spend some time reading it.

Also, it will certainly be of interest to people who are hooked on books such as “48 Laws of Power,” since Michel Foucault is the original and most influential theoretician of power and its relationship to knowledge and social control.

And “Discipline and Punish” is his most famous book on the subject.

About Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault was a French philosopher, historian of ideas and social theorist, extremely influential in areas as diverse as communication and cultural studies, feminism and literary theory.

was a French philosopher, historian of ideas and social theorist, extremely influential in areas as diverse as communication and cultural studies, feminism and literary theory.

Born in an upper-class family in France, Foucault earned degrees in philosophy and psychology at the Sorbonne (University of Paris).

After spending some time working as a foreign diplomat, in 1961, Foucault published “The History of Madness,” a massive volume which gained him instant recognition and respect.

He followed that up with few other structuralist books before being admitted to the Collège of France, a position he will retain until his death. In 1975, he published “Discipline and Punish” and just a year later “The History of Sexuality,” a four-volume work where he argued that sexuality is a social construct.

Ironically, a lifelong homosexual, Foucault died from HIV/AIDS complications in 1984, becoming the first public figure in France to die from the disease.

“Discipline and Punish Summary”

In case you didn’t know, “Discipline and Punish” is not merely something you can hear during a BDSM session, but also something people cite with reverence during many a-serious sociological and/or academic debate.

And the subtitle makes it clear what the book is about: the birth of the prison.

But, until we get there, we need to look at its pre-history.

Foucault, being a structuralist, isn’t that much interested in chronology as he is in structure.

Fortunately, his structure somewhat mirrors the chronology in this case: “Discipline and Punish” is divided into four interestingly titled parts: Torture, Punishment, Discipline, and Prison.

Torture

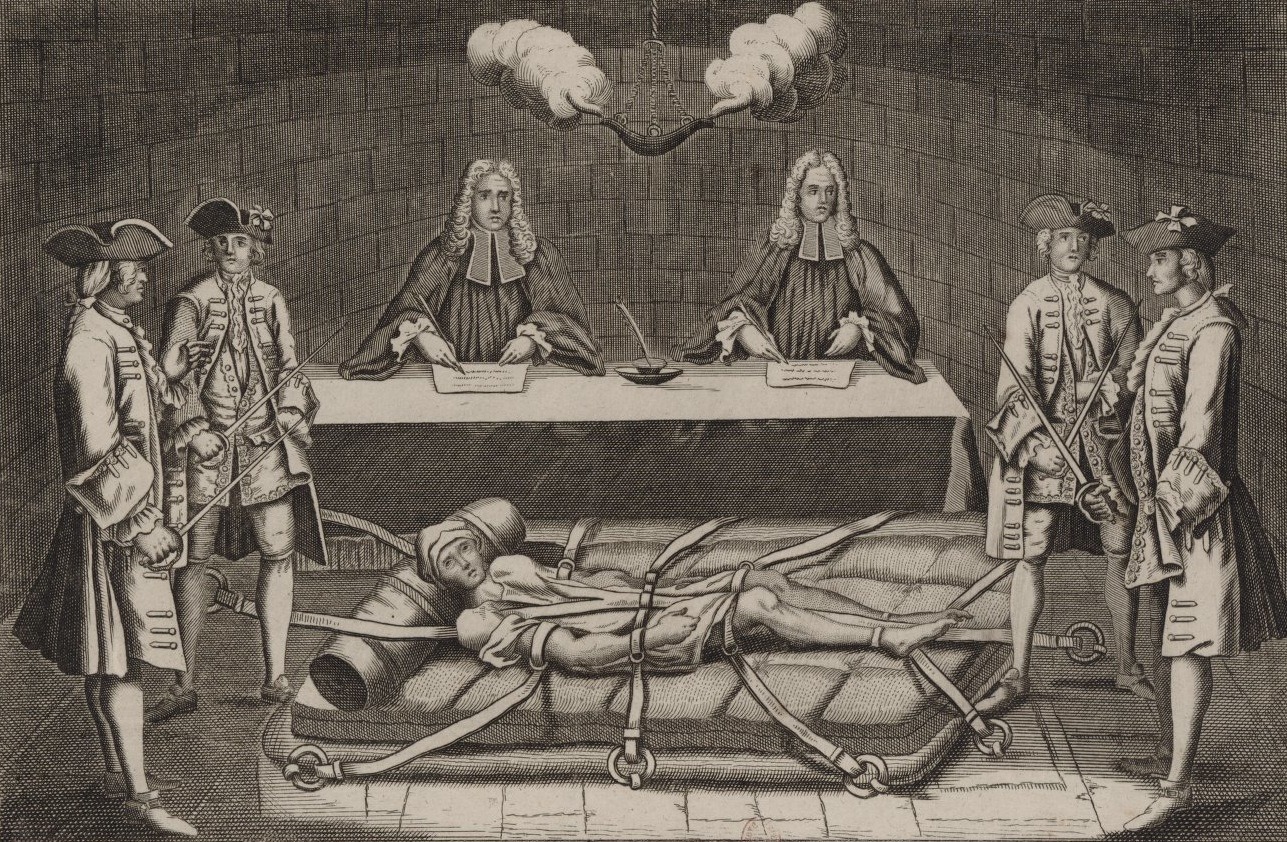

Have you ever heard of a guy called Robert-François Damiens?

If not, he was a domestic servant who tried to kill King Louis XIV back in 1757, unsurprisingly, the year he died.

This is how his judgment looked like:

Now, we would like to show you how his execution looked like as well, but we’re a reputable blog and, honestly, knowing what happened to him turns us away from even trying to find an appropriate image.

It suffices to say for now that Giacomo Casanova – the Casanova – was present at the execution and that he writes about it in his memoirs thus:

We had the courage to watch the dreadful sight for four hours … Damiens was a fanatic, who, with the idea of doing a good work and obtaining a heavenly reward, had tried to assassinate Louis XV; and though the attempt was a failure, and he only gave the king a slight wound, he was torn to pieces as if his crime had been consummated… I was several times obliged to turn away my face and to stop my ears as I heard his piercing shrieks, half of his body having been torn from him…

Oh, we forgot to mention:

Tearing his limbs to pieces was only the penultimate part of his punishment.

The rest of it included boots, hot wax, sulfur, molten lead, boiling oil and red-hot pincers before the dismemberment.

And, yes, burning at stake afterward.

Foucault’s question: how did we get from there to a prison?

Have we become more humane?

In the “Torture” section he sets the scene for the resounding “no” of the last part.

Because, you see, Foucault says, torture and prison are just different means by which those in power legitimate their power.

And prisons are just a more effective way to do this.

What was so wrong about tortures?

Well, let’s just say that Casanova wasn’t the only one who had to turn his eyes away from the scene.

Just a few years later, Cesare Beccaria condemned torture and death penalty in his seminal book on the subject “On Crimes and Punishments” by explicitly pointing out to the inhumanity of this punishment.

And about the same time, Thomas Paine, in “Rights of Man” cited Damiens’ death as the uttermost example of the extent of the cruelty of despotic governments.

And governments used public torture and executions for the exact opposite: to recover their power. To show everybody that a certain criminal was, in fact, a criminal and that he atones for his sins.

After the torture, in the eyes of many, Damiens, like King Lear, was more sinned against than sinning. And suddenly, instead of a failed assassin, he was on the brink of becoming a martyr.

As we have so tearfully learned from “Braveheart,” this is not a good thing for a government.

But, before we go on, we somehow feel that the scene deserves an inclusion:

Ah, this room can be a bit dusty from time to time…

Punishment

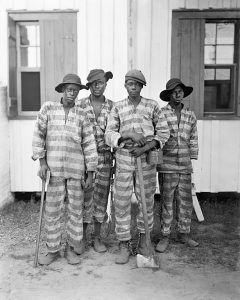

Before prisons came, however, there was also a period of, as Foucault says, “gentle punishments.”

Before prisons came, however, there was also a period of, as Foucault says, “gentle punishments.”

Or, in other words, punishments which transformed the public theater of execution into a mini-theater of signs and symbols.

We’re talking about that great little portrait on the left.

Yup, that’s a chain gang.

About a century later than the time Foucault is talking about, but – hey – the U.S. had slaves up until fifty years ago!

So, what’s behind the mini-theater of a convict lease?

Well, nothing more but disciplined torture.

In other words, a murdered criminal doesn’t worth as much as a criminal who pays for his crime by performing some manual labor for the good of society.

This worked – but with the advent of capitalism, the classes in power realized that there’s a better way to control the downtrodden.

Discipline

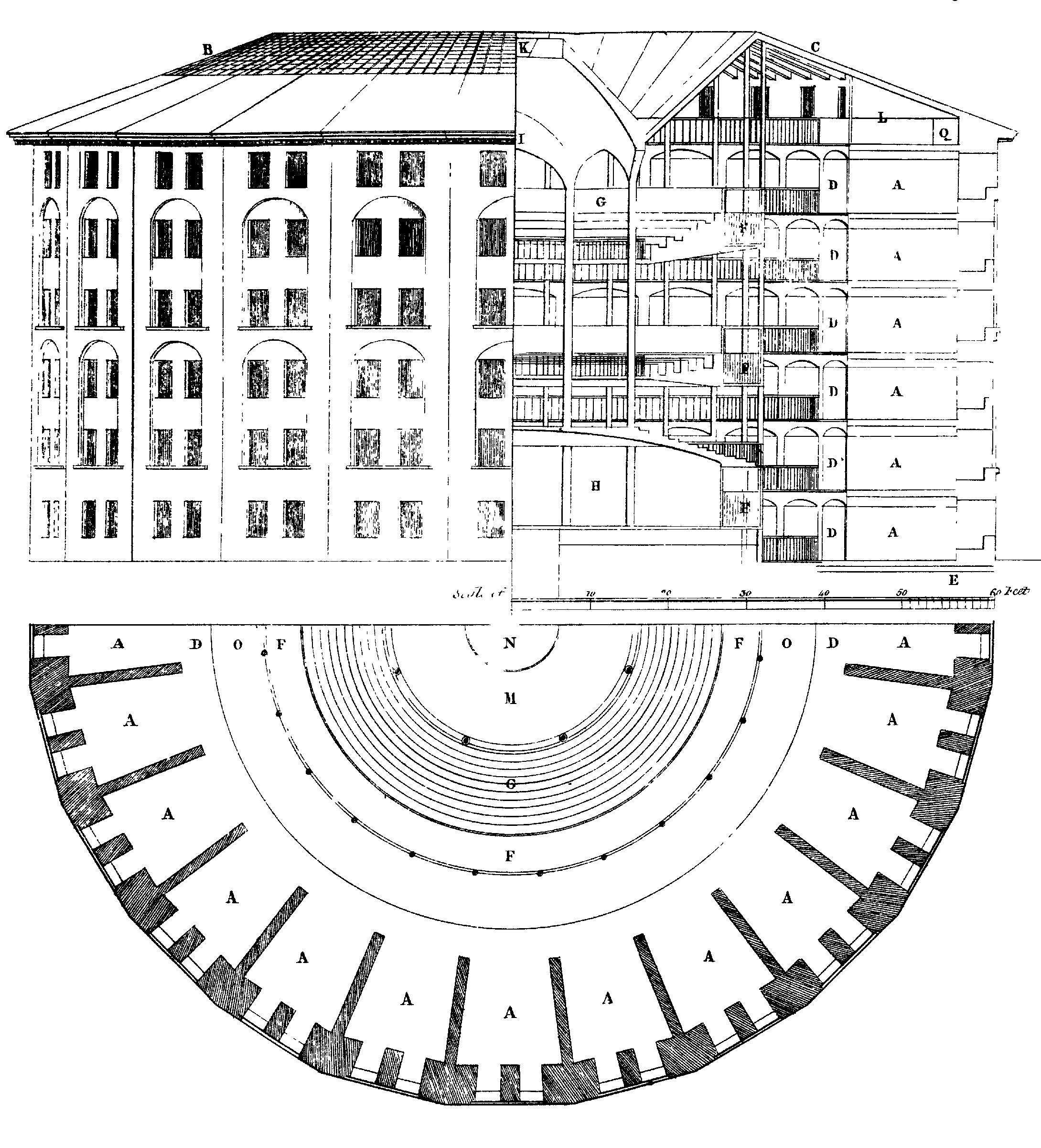

Before we go on, please, spend a minute or two thinking about this image:

That’s the plan of the Panopticon, devised by English philosopher Jeremy Bentham to allow a single watchman to observe all the inmates of an institution.

Or, as Bentham so lovingly put it, that’s “a mill for grinding rogues honest.”

It’s also one of the ways you are being controlled day in day out by those who want you to believe that you have a free will.

You know: the class struggle Marx was talking about in the world of power relations.

Can’t make the connection?

Keep on reading.

You see, even back in Ancient Greece, Plato was interested to find out how a state can control an invisible man.

His conclusion?

Tell everybody few “white lies” which will control them when they are not being watched.

Well, the technology of the 19th century made it possible for those in power to make one step more: to control (and nowadays, even watch) everybody all the time.

Just think about it!

By going to school or work everyday for at least eight hours; by having no more than few free days during a year; by staring at the TV (Netflix) or the computer screen (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) for at least five hours a day – you are in fact being trained by those in power to be their perfect subject.

Or, in Foucauldian terms, “a docile body.”

There’s no need for public executions anymore for a government to subjugate you. They will have the counter-effect.

What governments need is for you to believe that you are free.

Even though, through a series of institutions and mini-punishments (low grade, lower rating, bad review), they have successfully made you internalize the discipline they want you to be suppressed by.

A docile body is a body which scrolls through other people’s Facebook profiles even though it doesn’t have $5,000 to pay for its medical check-up.

Docile bodies don’t rebel.

Prison

Finally, the conclusion:

Prisons.

And it’s almost anti-climactic.

Because, as you have probably realized by now, prisons are nothing more but just a small part of the “carceral system” which is our society.

It is the system in which everyone is imprisoned.

In fact, our entire society is an extensive network of prisons.

We just call them by different names.

Factories, schools, military, hospitals, etc.

Key Lessons from “Discipline and Punish”

1. Public Executions May Result in Revolutions

2. Disciplinary Measures Produce Docile Bodies

3. You Are Living Your Whole Life in a Prison

Public Executions May Result in Revolutions

Foucault’s “Discipline and Punish” attempts to answer a simple question: why have we abandoned public tortures and opted to use prisons instead to punish delinquents?

In answering the first part of the question, Foucault analyzes the history of the public execution.

And shows that the problem with them is rather straightforward: they may incite the masses to rebel against the inhumane punishment exerted upon an individual.

And all governments use punishments for the exact opposite: to recover their power, which has been challenged by some crime.

Disciplinary Measures Produce Docile Bodies

At the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, the large-scale theater of public executions made way for the mini-theater of the chain gang.

And after some time, technology made it possible for those in power to control us in an even easier way.

Namely, through discipline.

They found out that discipline – whether at schools or factories – results in the internalization of the beliefs of the ruling class within the bodies of the subjected class.

Thus, creating docile bodies.

Which, for example, don’t even wonder why they have to be working 8 hours a day?

You Are Living Your Whole Life in a Prison

Consequently, prisons are just a small part of an extensive “carceral system” which the ruling elite has devised to control our behavior 24/7 and our life from the cradle to the grave.

Working 8 hours a day and not wondering why is basically on par with being publicly executed, if not even worse.

In the second case, it’s your body which suffers.

In the former – it’s your soul.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app, for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Discipline and Punish PDF Quotes”

The 'Enlightenment,' which discovered the liberties, also invented the disciplines. Share on X There is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations. Share on X Discipline 'makes' individuals; it is the specific technique of a power that regards individuals both as objects and as instruments of its exercise. Share on X it is the certainty of being punished and not the horrifying spectacle of public punishment that must discourage crime. Share on X In the darkest region of the political field the condemned man represents the symmetrical, inverted figure of the king. Share on XOur Critical Review

In the lecture series “Security, Territory, Population” – given a few years after “Discipline and Punishment” was published – Michel Foucault retracted a bit from some of the views laid bare in this book.

Interestingly enough, “Discipline and Punish” has remained unscathed and is still considered a key text in the history of ideas, breathing – as Peter Gay wrote – “fresh air into the history of penology and severely [damaging], without wholly discrediting, traditional Whig optimism about the humanization of penitentiaries as one long success story.”

Unsurprisingly, we highly recommend that you read it.

Though, prepare for a difficult read – Foucault’s ideas aren’t simple, and his style makes them even more complicated and tricky to grasp.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.

The Birth of the Prison

The Birth of the Prison