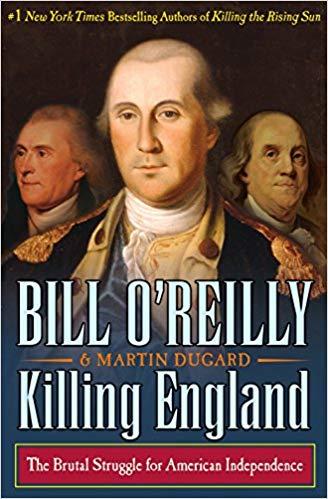

Killing England Summary

10 min read ⌚

The Brutal Struggle for American Independence

Ready for another chills-infusing dose of American patriotism?

If so, who better to inject you with it than Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard.

It’s the seventh book of the Killing series:

Who Should Read “Killing England”? And Why?

If you’re interested in American history, and you know a little about it, then Killing England will certainly interest you.

If, however, you are already deeply familiar with the lives of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and King George III and are not that keen on another story about the American Revolutionary War, then skip this one.

Unless you want to hear the same story retold in a new manner.

About Bill O’Reilly & Martin Dugard

Bill O’Reilly is an American political commentator, television host, and journalist.

In 1996, after anchoring for six years the tabloid TV program Inside Edition, Bill O’Reilly joined the Fox News Channel as the host of The O’Reilly Factor; “the biggest star in the 20 year history at Fox News,” The O’Reilly Factor was the highest-rated cable news show for over a decade and a half.

Following a “New York Times” article which revealed numerous sexual harassment lawsuits against Bill O’Reilly, Fox News terminated his contract.

Find out more at https://www.billoreilly.com/.

Martin Dugard is an American author of narrative non-fiction.

He is most famous for co-authoring – with Bill O’Reilly – all eight (so far) books in the Killing series.

In addition to this, he has also written a screenplay for a movie (A Warrior’s Heart), a few sports-related books and The Last Voyage of Columbus.

Find out more at https://www.martindugard.com/.

“Killing England PDF Summary”

Killing England’s POV

Published in 2017, Killing England is the seventh book – out of eight as of 2019 – in Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard’s pretty famous (but appallingly and oftentimes “misnomerly” titled) Killing series.

Those who have read even one of the relevant books in this series (Killing Lincoln, Killing Kennedy, Killing Reagan, Killing Patton, and especially Killing the Rising Sun or Killing the SS), already know the drill.

O’Reilly and Dugard’s starting position is usually “conservative America is the greatest country in the history of humanity,” and regardless of their focal point – Killing Jesus being the only exception – this is the point they are trying to make.

However, Killing England does surprise here and there: in 35 chapters, the book retells the brutal (and all too familiar) struggle for American independence but in a sort of playful manner, through the eyes of both the leaders of the British Empire and the main figures from the American Revolution.

Since this makes King George III one of the main characters of the book – and since there are at least a few chapters when events are told through his point of view – Interestingly enough, Killing England offers (sometimes, at least) a more balanced and nuanced view of the American Revolution than many other US-centered and US-glorifying books available on the market.

Killing England’s Structure and Prologue

It is both fairly difficult and fairly easy to summarize this book: the latter because you can find every single event in every single history book you’ve ever happened upon, the former because of the structure of Killing England.

Namely, each of the chapters tends to focus on one figure and one day (the period is, of course, 1775-1783), both of which are revealed in the opening sentence of the said chapter.

The only exception is the “Prologue” which is situated in Ohio Country and starts at 1:30 pm on July 9, 1755, the last day of the life of Capt. Daniel-Hyacinthe-Marie Liénard de Beaujeu.

Why?

Because that is the day that one of the four main characters of Killing England, George Washington, then a volunteer in General Edward Braddock’s army, redeems his honor after surrendering to the French at Fort Necessity the previous year and the day he ceases being a surveyor and Virginia gentleman to become a warrior.

Interestingly enough, this happens in a defeat: Braddock is soundly defeated at the Battle of the Monongahela by a force of French and Canadian troops.

Captain Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu dies, but dies a victorious hero.

Killing England’s Story

Since it’s both impossible and impractical to tell the story of Killing England as it is told by O’Reilly and Dugard (jumping from a character to character from one to the next chapter), we’ll summarize it neatly grouping the narrative arcs via the four main characters of the book.

No need to tell you that the characters in question are: George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George III.

George Washington

After introducing us to the so-called Bradock’s Disaster and George Washington’s resignation from Britain’s military service, Dugard and O’Reilly jump two decades ahead (to June 16, 1775) and present the now 41-year-old Washington in a completely new light:

Twenty years almost to the day after Braddock’s Defeat, as the infamous battle in the Ohio River Valley has come to be known, the six-foot-two Virginian pushes back his chair and rises to his feet. Seventy-year-old Benjamin Franklin watches him from across the cramped Assembly Room here in the Pennsylvania State House. Delegates to the Second Continental Congress sit in high-backed chairs, their papers splayed before them on cloth-covered tables, waiting to hear if Washington will accept the new title he has been offered.

Nominated by Samuel and John Adams – to the utter joy of everyone present – Washington accepts this new title (Commander in Chief of the newly-formed Continental Army).

“As to pay, Sir,” he says in his acceptance speech, “I beg leave to assure the Congress, that, as no pecuniary consideration could have tempted me to have accepted this arduous employment, at the expense of my domestic ease and happiness, I do not wish to make any profit from it.”

The rest is (pretty known) history.

As the very first Commanding General of the United States Army, George Washington leads the Continental Army to many victories, most notably in the first battle fought after the Declaration of Independence and the largest one of the whole war (The Battle of Long Island), and, more importantly, the morale-boosting Surrender of Yorktown which prompts the British government to negotiate an end to the conflict.

No wonder Washington is still remembered as the “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin’s biography is just too colorful to be retold in a few hundred words – or even a few hundred pages, for that matter.

Justly considered “The First American” in history, Franklin was a polymath who was capable of turning into gold basically everything he would touch.

Known for inventing the Franklin stove, bifocals, and (most notably) the lightning rod, Franklin was everything from a leading author to a publisher, from a still-quoted physicist to one of the foremost scientists of his time, from a smart politician to a Grand Master Freemason.

As far as America’s efforts to kill England, for the most part of his life, he was impartial and pacifistic. “In England,” he wrote describing the effects of this, “I am accused of being too much an American, and in America of being too much an Englishman.”

O’Reilly and Dugard follow Benjamin Franklin from his ambassadorship day to France through his change of mind in relation to the new country to his career as the first United States Postmaster General.

However, O’Reilly and Dugard don’t shy away from portraying Ben Franklin’s dark side as well, as well as his reputation as a sort of a ladies’ men.

This, of course, means that Benjamin Franklin wasn’t that great of a husband or a father, and Killing England uncovers quite a few interesting events related to this side of “the most accomplished American of his age.”

Here’s an interesting bit (you probably already know): Benjamin Franklin’s illegitimate son William fought for England because he hated his father more; in addition, he exiled himself after learning that Benjamin Franklin planned to arrest him.

Needless to add, the two never spoke again after this.

Thomas Jefferson

Understandably and quite expectedly, Thomas Jefferson’s narrative arc mostly focuses on him writing the Declaration of Independence.

As everybody knows, he was recommended to do that by John Adams, whose reasons to choose Jefferson before him were threefold:

• First of all, unlike Adams who was from Braintree, Massachusetts, Jefferson was a Virginian, “and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business;”

• Secondly, USA’s third president was everything the country’s second president was not, in Adams’ words not an “obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular” person;

• And thirdly and more importantly, in Adams’ words, Jefferson could write ten times better than him.

In retrospect, it seems that Adams was right on at least this last account: the Declaration of Independence is one of the pinnacles of elegant political writing, and its preamble is, by all accounts, one of the highlights in humanity’s history:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

About that “all men are created equal” part…

Thomas Jefferson was a fairly rich slaveowner who most probably fathered six children with one of his slaves, a mixed-race woman named Sally Hemings, born four decades after USA’s third president.

Well, it seems that George Orwell was right: some humans are created more equal than others.

King George III

Killing England surprises the most in its pretty neutral representation of King George III of the United Kingdom.

George was merely 22 years old when he was coronated in 1760, and ruled England during the most tumultuous times of its glory years as a colonial superpower.

England was already in war with (mainly) France for global military and political primacy at the time of his coronation and, in 1763, after the Treaties of Paris and Hubertusburg, Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War was joyously celebrated on the American continent.

Hell, we’ll go even further than that: George III was celebrated as a hero, and the future Americans reveled in the fact that they were citizens of the world’s greatest and most powerful empire.

However, Britain’s victory came at a hefty price: according to George Grenville, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Britain’s budget deficit in 1763 was in excess of £122 million.

And America was just too big and attractive place to collect new taxes.

Of course, the Americans (especially the three guys from the chapters above) didn’t share this opinion with King George III (they believed they were British and, thus, have the same rights as the English) and that’s how the American War for Independence broke out.

Even though some historians accuse King George of fighting too long a lost war, O’Reilly and Dugard are far more sympathetic: he was just doing what his position demanded him to do.

And until the Siege of Yorktown, many still believed in a British victory.

However, that didn’t happen, and George accepted the defeat.

“I was the last to consent to the separation,” he told John Adams in 1785, “but I would be the first to meet the friendship of the United States as an independent power.”

Postscript

Killing England includes a long postscript in which the later days of most of the characters mentioned in the book are related.

The final paragraph, as if a before-credits title card, reveals neutrally and chillingly the numbers and figures of the American War of Independence:

An estimated 400,000 Continental soldiers and state militia fought on the American side through the course of the war. There is no exact number.

It is thought that almost 7,000 American soldiers were killed in action during the war, with many more deaths coming from disease or from the harsh conditions endured as prisoners of war. Those mortality figures are roughly 17,000 and 12,000, respectively, bringing the total casualty figure to an estimated 36,000.

British casualties were estimated to be 24,000 killed in battle, missing in action, and dead from disease. Of the 30,000 Hessians who fought in the war, one-fourth either were killed in action or died from illness. Some 5,500 Hessian soldiers chose to remain in America following the war.

Many soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War were given tracts of land by the new federal government, settling America and continuing the growth made possible by their service.

Key Lessons from “Killing England”

1. The American War of Independence Was Not Inevitable

2. Benjamin Franklin’s Son Fought Against His Father

3. Thomas Jefferson Fathered Six Children with His Wife’s Half-Sister

The American War of Independence Was Not Inevitable

Even though, in retrospect, one could argue that it was inevitable that it would happen sooner or later, it seems that Britain’s bad tax strategy is to blame for the American Revolutionary War.

Not only most of the Americans rejoiced after Britain won the Seven Years’ War against France in 1763, but also some of the leaders of the American Revolution – such as, say, Benjamin Franklin – were firmly against independence not that long before the war broke out.

Benjamin Franklin’s Son Fought Against His Father

In matters public and intellectual, Benjamin Franklin was the foremost American of his time; however, as far as his personal life is concerned, he was quite the Casanova with the ladies and quite the Darth Vader with his illegitimate son William.

William hated him so much, in fact, that he fought against America during the War for Independence and exiled himself after Benjamin wanted to arrest him for that.

Thomas Jefferson Fathered Six Children with His Wife’s Half-Sister

Thomas Jefferson may have written the most famous line in American history – “all men are created equal” – but he didn’t practice it in his personal life.

On the contrary, he was a slave owner and, moreover, he fathered six children with one of his slaves, a mixed-race woman by the name of Sally Hemings.

To make matters even worse, Sally was basically a half-sister of Jefferson’s first and only wife, Martha.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Killing England Quotes”

The most important six hours in America’s short history are about to take place. A defeated George Washington vows to be the last man out. Click To Tweet The French have long been waiting for a sign that the Americans can actually win this war. Click To Tweet An estimated 400,000 Continental soldiers and state militia fought on the American side through the course of the war. There is no exact number. Click To Tweet The people voted overwhelmingly for Washington. John Adams came in second, and thus won the job of vice president. Click To Tweet America has its first president. The destiny of the republic is under way. Click To TweetOur Critical Review

Even though Killing England sold the least number of copies when compared to the other books of the Killing series (65,000 in its initial week, less than half of Killing the Rising Sun and only a third of Killing Patton), it may be, in our opinion, one of the better books of the series.

It is not only enthralling and enjoyable: it is also finely researched and bereaved of prejudice; recommended for history buffs.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.