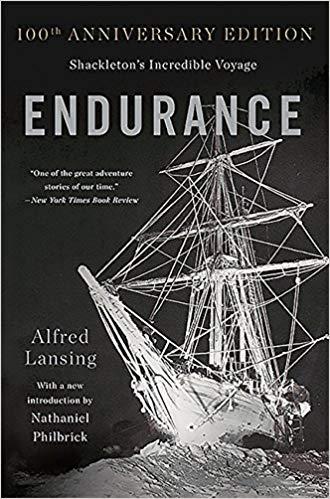

Endurance Summary

11 min read ⌚

Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage

Do you want to hear all about the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration?

Then look no further: Alfred Lansing’s classic Endurance is its best and most spellbinding account.

And we have the summary!

Who Should Read “Endurance”? And Why?

If you are interested in the history of exploration – and especially the exploration of the Antarctic region during the first quarter of the 20th century – then Endurance is one of the classic books on the subject.

Hundred years after the original expedition, Shackleton’s endeavor is even more interesting to people who investigate the traits and essence of great leadership. See why.

Alfred Lansing Biography

Alfred Lansing was an American journalist and writer, best known for his 1957 classic, Endurance.

Born in Chicago on July 21, 1921, Lansing served the U.S. Navy during the Second World War and received a Purple Heart for being wounded during his service. Afterward, he enrolled at North Park College and later at Northwestern University, where he majored in journalism.

He edited a weekly newspaper between 1946 and 1949, before joining the United Press and becoming a freelance writer in 1952.

With Walter Modell, Lansing co-authored one of the last books from the Life Science Library, Drugs (1967). Just eight years later, he died, aged 54.

Plot

First discovered by a Russian expedition in 1820, the continent of Antarctica became an object of fascination for numerous explorers around the world during the last years of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century. To history buffs and readers of exploration literature, this period is mostly known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

For a reason: during the Heroic Age, no less than 17 major Antarctic expeditions were launched from 10 different countries of the world. Though some of them had scientific interests, the primary object of most of these expeditions was, interestingly, to become the first expedition to reach the geographic South Pole.

That happened in December 1911, when a highly prepared Norwegian expedition led by Roald Amundsen decisively beat the (ironically) better-remembered one led by a British Royal Navy Officer named Robert Falcon Scott.

However, Alfred Lansing’s Heroic Age classic, Endurance, is not about Robert Falcon Scott—a celebrated hero of his day and age, but also someone whose leadership qualities and competence of character have been questioned in recent times—but about one of his officers during previous journeys, Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton.

And it’s not about merely reaching the South Pole, but about something even more daunting and unimaginable: crossing the entire continent from sea to sea, via the pole.

Why would someone set before himself such a goal? Well, maybe it’s best if we dedicate the first two sections of our summary to answering this question.

The Protagonist: Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton

Born on February 15, 1874, in Ireland, Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton is now widely considered one of the principal figures of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

His first experience of the polar regions came relatively early: he was in his 20s when he was assigned the role of third officer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s landmark Discovery expedition of 1901–1904 that was organized by the British Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society with the objective of carrying out scientific research and geographical exploration of the untouched continent.

It was during this trip that he, Scott, and another companion set a new southern record (82°S), which Shackleton would better just a few years later during the Nimrod expedition (88°S). However, when Amundsen reached the Farthest South latitude (90°S) on December 15, 1911, Shackleton was a bit shackled.

It was almost as if he had nothing to accomplish anymore. But, restless and resolute as he was, just a few years later, he turned to the “one great object of Antarctic journeyings” remaining: a transatlantic journey, i.e., crossing Antarctica from the Wendell Sea via the South Pole to McMurdo Sound.

Lansing describes Shackleton’s appearance in a vivid manner:

He was now forty years old, of medium height and thick of neck, with broad, heavy shoulders a trifle stooped, and dark brown hair parted in the center. He had a wide, sensuous but expressive mouth that could curl into a laugh or tighten into a thin fixed line with equal facility. His jaw was like iron. His gray-blue eyes, like his mouth, could come alight with fun or darken into a steely and frightening gaze. His face was handsome, though it often wore a brooding expression—as if his thoughts were somewhere else—which gave him at times a kind of darkling look. He had small hands, but his grip was strong and confident. He spoke softly and somewhat slowly in an indefinite baritone, with just the recollection of a brogue from his County Kildare birth.

And then he adds something even more central about his character, something almost superhuman in an Ahab-or-Santiago-kind-of-way: “Whatever his mood—whether it was gay and breezy, or dark with rage—he had one pervading characteristic: he was purposeful.”

The Objective and the Plan of the Expedition

The British didn’t take the news of the Norwegians reaching the South Pole before them lightly. Their record for exploration “had been perhaps unparalleled among the nations of the earth,” and now they had to take “a humiliating second-best” to a much less-renowned country.

Things took a turn for the worse when the news of Robert Falcon Scott’s tragic death reached England. The whole nation was saddened. In a way, Shackleton used this to his benefit while soliciting funds for his Trans-Antarctic expedition, playing “heavily on this matter of prestige, making it his primary argument for such an expedition.

“From the sentimental point of view,” he wrote once, “it is the last great Polar journey that can be made. It will be a greater journey than the journey to the Pole and back, and I feel it is up to the British nation to accomplish this, for we have been beaten at the conquest of the North Pole and beaten at the first conquest of the South Pole. There now remains the largest and most striking of all journeys—the crossing of the Continent.”

Shackleton’s plan—which owed a lot to an abandoned one penned by Scottish explorer, William Speirs Bruce—looked something like this:

Shackleton’s plan was to take a ship [named Endurance] into the Weddell Sea and land a sledding party of six men and seventy dogs near Vahsel Bay, approximately 78° South, 36° West. At more or less the same time, a second ship [named Aurora] would put into McMurdo Sound in the Ross Sea, almost directly across the continent from the Weddell Sea base. The Ross Sea party was to set down a series of food caches from their base almost to the Pole. While this was being done, the Weddell Sea group would be sledding toward the Pole, living on their own rations. From the Pole they would proceed to the vicinity of the mighty Beardmore Glacier where they would replenish their supplies at the southernmost depot laid down by the Ross Sea party. Other caches of rations along the route would keep them supplied until they arrived at the McMurdo Sound base.

Of course, not everybody was impressed: in some circles, this undertaking was criticized not only as being too “audacious,” but also being kind of “impossible.” Perhaps it had been both. But, as Lansing says, “if it hadn’t been audacious, it wouldn’t have been to Shackleton’s liking. He was, above all, an explorer in the classic mold—utterly self-reliant, romantic, and just a little swashbuckling.”

(By the way, if you have problems following Shackleton’s plan—and the rest of his journey—we sincerely advise you to click here: once again, Wikipedia’s contributors have provided the most intelligible map on the Internet).

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

October 1914—January 1915: The Trapping of Endurance

Ernest Shackleton’s 28-man expedition set sail on October 26, 1914, from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Nine days later, the ship (both prophetically and ironically—for reasons you’ll discover soon—named Endurance) reached the first stop of the journey: the Grytviken whaling station on South Georgia. Whalers there reported something portentous: the conditions in the Weddell Sea were the worst they could remember.

Shackleton—for reasons explained above—barely even took this into consideration. A month later, on December 5, 1914, Endurance left South Georgia. Unfortunately, just two days later it encountered the first ice pack on their journey. Somehow, they managed to sail through it after about two weeks. The fact they drifted about 60 nautical miles from their intended target didn’t matter much: it was bearable.

But, very soon—in the middle of January 1915, to be exact—they happened upon another ice pack, some 200 miles from Vahsel Bay. This one they couldn’t get through: they got stuck immobile inside and had no choice but to leave Endurance drift away with the pack ice for the next several months. Eventually, they lost sight of land completely: in fact, due to the Weddell Sea current, they started circling back to South Georgia and they were further and further away not only from their target but also from any land whatsoever.

January 1915—October 1915: The Sinking of Endurance

To make matters worse, soon the Antarctic summer (which coincides with our winter) ended and the endless polar nights began. “In all the world there is no desolation more complete than the polar night,” writes Lansing. “It is a return to the Ice Age—no warmth, no life, no movement. Only those who have experienced it can fully appreciate what it means to be without the sun day after day and week after week. Few men unaccustomed to it can fight off its effects all together, and it has driven some men mad.”

To stop this from happening and neutralize the depression as much as possible, Shackleton organized Sunday evening gramophone concerts and monthly lectures by the Endurance’s photographers, among many other jolly events that helped the sailors keep their spirits up.

By late October 1915, still frozen immobile in the enormous ice pack, Endurance drifted over 500 nautical miles to the north-east. To make matters even worse, the ice had thickened in the meantime and Endurance had to endure much more pressure from the surrounding pack.

On October 27, 1915, it finally succumbed: the ice started crushing the boat.

October 1916—March 1916: Living on an Ice Pack

Immediately understanding the extent of this new misfortune, Shackleton had no choice but to order his crew to leave Endurance and start building a camp on a nearby floe of ice, while salvaging as much material and food as possible.

During the next month or so, everything was stockpiled on the floe. On November 21, 1915, Endurance entirely sank beneath the sea.

Since the floe to which Shackleton’s crew had initially set a camp had also crumbled under pressure in the meantime, the crew had to relocate. Hoping that a new ice floe will drift them to safety, on December 29, Shackleton sets a new camp on another ice pack, and dubs him “The Patience Camp.”

The Patience Camp would be the crew’s home for the first third of 1916. While there, they would make a few attempts to sled over the ice, but all of them would prove to be unsuccessful.

It is only due to Shackleton’s ability to motivate his people that the crew hasn’t given up altogether at this point. They eat penguins and seals, occasionally killing dogs as well, to conserve food.

March 1916—April 1916: Voyage to Elephant Island

In March 1916, the ice floe where the Patience Camp is located successfully makes its way to about 60 miles from Paulet Island, but impassable conditions make floating to the island all but an impossible goal.

Soon after, to the dismay of the crew, the ice floe begins to break, and Shackleton has to plan a trip to some kind of a nearby land—using nothing more than three lifeboats.

On April 9, 1916, the ice pack breaks in two, and The James Caird, Stancomb Wills and Dudley Docker are launched for a voyage to Elephant Island, a remote and uninhabited island far from all shipping lanes. But also, at this point, Shackleton’s crew’s only hope.

After six miserable days, the three lifeboats land on Elephant Island on April 15, the first time that the 28 men touch solid ground after precisely 497 days!

Though remote and uninhabited, Elephant Island is much more reliable than a lifeboat or an ice floe, so the crew is happy and relieved. Shackleton is not: he knows that this is merely the beginning of the rescue journey.

April 1916—May 1916: Reaching the Stromness Whaling Station

Barely nine days after setting up a camp at Elephant Island, Shackleton chooses the five strongest men in his crew— Captain Frank Worsley, second officer Tom Crean, carpenter Chippy McNeish, and seamen Tim McCarthy and John Vincent—and the best boat—the James Caird—and sets off for South Georgia, where a whaling station is located and where he hopes to get some help.

The extremely dangerous journey lasts for two weeks. But finally, on May 10, the James Caird reaches the south coast of South Georgia! Unfortunately, they reach land there on the far side of the island.

So, merely a few days after reaching South Georgia, the exhausted Shackleton, Crean and Worsley—facing the fact that the James Caird is now too unseaworthy to use it to go round the island—set out on yet another dangerous and never-before-done journey to reach the Stromness whaling station by crossing South Georgia on foot!

About a day later, the three men are stirred to hear the sound of a factory whistle:

A peculiar thing to stir a man—the sound of a factory whistle heard on a mountainside. But for them, it was the first sound from the outside world that they had heard since December 1914—seventeen unbelievable months before. In that instant, they felt an overwhelming sense of pride and accomplishment. Though they had failed dismally even to come close to the expedition’s original objective, they knew now that somehow they had done much, much more than ever they set out to do.

Finally, the men reach the Stromness whaling station, and Worsley immediately sails back to pick up the three men left behind.

May 1916—August 1916: The Rescuing of the 22 Men Left Behind

The mission is not complete, though: there are 22 men still on Elephant Island and they are all waiting to be saved.

During the months of May and June, using borrowed ships (Southern Sky, Instituto de Pesca No. 1, and Emma), Shackleton embarks on a series of unsuccessful rescue attempts to reach Elephant Island, where the other men of his crew have, in the meantime, all but given up on hope.

Finally, on August 30, 1916, during his 4th rescue attempt aboard the steam tug Yelcho (loaned to him by the Chilean government), Shackleton reached Elephant Island and rescued all 22 remaining members of his original expedition, 2 years and 22 days since leaving England.

On September 3, 1916, the Yelcho reached Punta Arenas, with all 28 members of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition aboard.

Endurance Epilogue

After his death, the name of Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton—who died in debts due to many failed business endeavors—was largely forgotten by both his compatriots and the world, contrary to that of his one-time captain and longtime rival afterward, Robert Falcon Scott.

However, in the decades that followed, things changed, and nowadays it is Scott whose heroism and leadership qualities are often questioned, while Shackleton’s name has become almost synonymous with the word “leadership.”

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Endurance Quotes”

No matter what the odds, a man does not pin his last hope for survival on something and then expect that it will fail. Click To Tweet We had seen God in His splendors, heard the text that Nature renders. We had reached the naked soul of man. Click To Tweet Of all their enemies—the cold, the ice, the sea—he feared none more than demoralization. Click To Tweet The rapidity with which one can completely change one’s ideas . . . and accommodate ourselves to a state of barbarism is wonderful. Click To Tweet I long for some rest, free from thought. Click To TweetOur Critical Review

There’s a reason why people remember Alfred Lansing for this book, and why they remember Shackleton’s failed expedition primarily through it: Endurance is an exceptionally researched and beautifully written book on a topic

And by “beautifully written,” we mean “written in a way they don’t write books anymore”: Lansing’s prose belongs more to the 19th century than to the modern age, but that should be off-putting only to those who, unlike the protagonist of the book, are not persistent and tenacious enough to swim through the breathtaking layers of meaning and reach the surface both richer and more perceptive. A classic of exploration literature, Endurance is a story of heroic failure, and since heroic failure touches people even more than heroic success, it’s bound to remain engraved in your memory for quite some time.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.