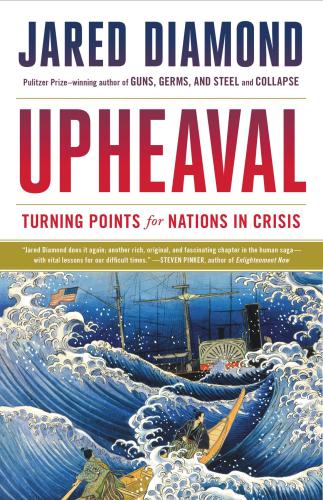

Upheaval Summary

18 min read ⌚

How Nations Cope with Crisis and Change

Ever experienced a personal crisis? Sure, you have! But have you ever wondered whether what you did during a personal crisis of yours can be applied to a nation in crisis?

Well, American polymath Jared Diamond has, and he thinks the answer to the previous question is “yes.” Allow him to make his argument in the majestic, “comparative, narrative, exploratory study of crisis and selective change” that is:

Who Should Read “Upheaval”? And Why?

If you are a history buff or a student of political science, then Upheaval has everything you might want to find in a book: wars, crises, sadistic dictatorships, economic policies, and the building of new nations.

But then again, it’s a Jared Diamond book, so that’s all but a given once you see his name on the cover. The only thing that’s left for you is to enjoy.

About Jared Diamond

Jared Mason Diamond is an American polymath—geographer, biologist, anthropologist, physiologist—and the author of several immensely popular science books, such as Guns, Germs, and Steel, The Third Chimpanzee, and Why Is Sex Fun?

A professor of geography at UCLA, he is one of the most respected public intellectuals in the world, recently ranked the 9th most influential public intellectual in a joint poll by “Prospect” and “Foreign Policy.”

Find out more at http://www.jareddiamond.org

“Upheaval Summary”

“At one or more times during our lives,” writes Jared Diamond at the beginning of the “Prologue” to Upheaval, “most of us undergo a personal upheaval or crisis, which may or may not get resolved successfully through our making personal changes.”

“Similarly,” he adds instantly, “nations undergo national crises, which also may or may not get resolved successfully through national changes. There is a large body of research and anecdotal information, built up by therapists, about the resolution of personal crises. Could the resulting conclusions help us understand the resolution of national crises?”

And that is what Upheaval is all about.

Diamond’s beautiful description, is “a comparative, narrative, exploratory study of crisis and selective change operating over many decades in seven modern nations… and viewed from the perspective of selective change in personal crises. Those nations are Finland, Japan, Chile, Indonesia, Germany, Australia, and the United States.”

Just look at a map of the world, and you’ll understand why these are the nations Diamond chose: in addition to having much personal experience with all of them, they also cover many distinctly different cultures and are located on all sides of the world.

But before devoting the rest of his book to national crises, Diamond reserves the introductory chapter for personal crises, believing that the factors that influence the likelihood of a personal crisis being successfully resolved have their parallels as far as the outcomes of national crises are concerned.

So, let’s start there.

Part 1: The 12 Factors Related to the Outcomes of Personal and National Crises

Personal crises are inevitable.

Whether sudden or gradual, whether in adolescence or after retirement, you must have experienced at least one.

And since everybody has, therapists have spent a lot of time analyzing their genealogy, their possible extent, and the ways one can overcome them. During this research, they have identified “at least a dozen factors,” which suggest whether an individual will or won’t succeed in resolving a personal crisis.

These 12 factors are the following:

1. Acknowledgment that one is in crisis

2. Acceptance of one’s personal responsibility to do something

3. Building a fence, to delineate one’s individual problems needing to be solved

4. Getting material and emotional help from other individuals and groups

5. Using other individuals as models of how to solve problems

6. Ego strength

7. Honest self-appraisal

8. Experience of previous personal crises

9. Patience

10. Flexible personality

11. Individual core values

12. Freedom from personal constraints

Most of the factors on the list above have “recognizable analogs” in the case of national crises (1-5 and 7-8), two are less specifically linked (9 and 12) and in the cases of three (6, 10 and 11), the individual factor serves just as a metaphor suggesting a factor describing nations.

Consequently, the 12 factors that Diamond believes are related to the outcomes of national crises are as follows:

1. National consensus that one’s nation is in crisis

2. Acceptance of national responsibility to do something

3. Building a fence, to delineate the national problems needing to be solved

4. Getting material and financial help from other nations

5. Using other nations as models of how to solve the problems

6. National identity

7. Honest national self-appraisal

8. Historical experience of previous national crises

9. Dealing with national failure

10. Situation-specific national flexibility

11. National core values

12. Freedom from geopolitical constraints

It is through these factors that Diamond is interested in analyzing several 20th-century crises (mostly) he was able to observe in person and in real-time; he dedicates the second part (i.e., most of his book) to these. The same holds true for our summary.

Part 2: National Crises

Finland’s War with the Soviet Union

As you probably know, Finland is a Scandinavian country of about 6 million people which borders Sweden to the west and Russia to the east. We’ll be very surprised if you know something more than this, however: Finland wasn’t even a free country for most of history.

From the 13th to the 19th century it was considered a part of Sweden, but after 1809, it became a part of Russia. It remained so for the next century: during the Russian Revolution of 1917, fed up with an oppressive governor set by the Russian Tsar Nicholas II, Finland decided it has had enough and proclaimed its independence.

Unfortunately, being a small and rather undeveloped country located next to the biggest country in the world was a sure recipe for problems. They got even bigger after the newly independent Finland became a liberal capitalist democracy, and the USSR the first communist country in the world.

All hell broke loose when Stalin became the President of the Soviet Union due to the very simple fact that he didn’t know what the words “compromise” or “negotiation” meant.

It started that way, though: stating security reasons (defending Leningrad), the Soviets asked for some Finnish territories (in exchange for others), and, when Finland refused, on November 30, 1939, just three months after World War II had started, Stalin ordered an invasion of Finland.

The event triggered what is generally known as the Winter War, a military conflict that officially lasted until March 13, 1940, and unofficially it went on throughout the war.

USSR, of course, won the Winter War, but, due to very smart tactics employed by the Finnish volunteers (camouflage, snipers, Molotov cocktails, and machine guns), it suffered heavy losses (8 Soviet soldiers killed for every Finnish one), not to mention the bulk of its still fragile international reputation.

The most controversial tactic the Finns employed, however, was allying with the Nazis, hoping the Germans would help them defend from Soviet attacks.

They realized soon after that the Germans were not precisely the best ally one could have and started finally realizing that their crisis stemmed from a factor they could do nothing about geography.

So, they smartly started building a fence to delineate the problems and think about solutions and adopted a new stance toward the Soviet Union to overcome the crisis once and for all.

For one, they declined to support the German troops in Leningrad—possibly a turning point not only in the Battle of Leningrad but in the Second World War altogether. Of course, this was appreciated by everyone (including Stalin), so the Soviet planes started deliberately missing Finnish targets, dropping their bombs in Finnish waters.

However, since Finland was on the losing side after the war, it was still required that it pays $300 million to the USSR in reparations—in little over half a decade.

The Finns, true to Churchill’s adage to never let a good crisis go to waste, started looking at their crisis differently, using it to industrialize themselves and develop trading connections with everybody—above all, with the Soviet Union.

They also agreed to not talk ill about anything bad happening in the USSR, but self-censorship is not that bad a price to pay for earning your independence and developing a prosperous country on the very border of a mighty enemy.

After all, that’s how selective change works: you do what you can to achieve the necessary (good neighborly relations) and accept what you can’t change (the neighbor) even if it means sacrificing a bit of your former self.

The Origins of Modern Japan

Today, Japan is considered one of the great powers of the world, its economy being the world’s third-largest by GDP and fourth-largest by purchasing power parity.

However, up until the second half of the 19th century, it was a feudal society, almost completely isolated from the world and uninterested in becoming a part of the modern technological processes.

And then, just like the USSR did in the case of Finland, the US forced Japan to modernize and become the country it is today.

It all started with the US discovering gold in California. As a result, it needed new ports to refuel its boats along its Pacific Ocean trading routes. US President Millard Fillmore asked for access to some of Japan’s ports in 1853, but he didn’t do it nicely: it was either that or something much worse.

Though the rulers of Japan weren’t so happy with a deal that practically got them nothing in return, they realized they had to make it, for they were no match to one of the fastest-developing and military most advanced countries in the world.

However, this caused an internal crisis: most of the Japanese (especially the Samurai) were against such a deal, so a coup and civil war followed. It resulted in what is today known as the Meiji era, a period of forty or so years during which Japan evolved from a feudal society to a modern, industrialized nation, and became one of the world’s emergent great power.

Wait a minute, you say! But wasn’t the coup against this?

Yes, it was. But, as soon as they were installed, the new leaders realized that Japan risks being colonized by European superpowers unless it became a superpower itself.

Thus, Japan made the first step toward overcoming its crisis: acknowledging its situation and performing an honest-self assessment. Now, was the time for selective changes.

True to the 12-step therapeutic program, Japan took other countries as role models: Germany for its constitution and army, Britain for its military ships and its navy.

However, they didn’t change entirely: they accepted many elements from the Western societies they were trying to emulate, but they remained true to most of their traditions, creating a unique blend of Asian patience and self-sacrificing character with a Western thirst for freedom and individualism.

The result?

They defeated the Russians during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 and announced to the world that they were a force to be reckoned with.

True, Russia was ruled ineffectively by Tsar Nicholas and was all but a feudal state, but this was, after all, the first victory of an Asian power over a European enemy.

A Chile for All Chileans

Unlike most of the South American countries, Chile was a democratic nation for most of its existence. Ever since 1925, the country’s voting system prevented any of its three parties (left, centrist, and right) from taking total control.

It was so in 1970 as well, when Marxist Salvador Allende was chosen to be the President with about 36 percent of the vote. Even though—to quote a Chilean friend of Diamond—he had good ideas, Allende executed them poorly, adopting wrong solutions to the problems in question.

Most importantly, Allende ignored the fact that only a third of the Chilean voters gave him support and that mighty powers (such as the Chilean armed forces, the Chilean capitalists, and, most importantly, the United States government) were among the two-thirds who were against him.

Yet, he nationalized US-owned copper companies, froze prices, replaced free-market elements of Chile’s economy with socialist-style state planning, granted big wage increases, greatly increased government spending, and printed paper money to cover the resulting government deficits.

The result?

Polarization of the political climate brought an end to Chile’s democracy and installed a dictator in Allende’s place who was either murdered or committed suicide.

This is how Diamond sums up the situation:

On September 11, 1973, after years of political stalemate, Chile’s democratically elected government under President Allende was overturned by a military coup whose leader, General Pinochet, remained in power for almost 17 years. Neither the coup itself nor the world records for sadistic tortures smashed by Pinochet’s government had been foreseen by my Chilean friends while I was living in Chile several years before the coup. In fact, they had proudly explained to me Chile’s long democratic traditions, so unlike those of other South American countries. Today, Chile is once again a democratic outlier in South America, but selectively changed, incorporating parts of Allende’s and parts of Pinochet’s models.

Believe it or not, even though Chile’s democracy turned into a sadistic dictatorship in the span of just a few years, Pinochet’s decision to turn over the economy to Milton Friedman and the Chicago Boys was very beneficial in the long run.

True, Chile never re-privatized the copper mines (still responsible for 10% of Chile’s GDP), but everything else was left to the free market to decide. They decided that Chile will become the country with the highest GINI coefficient (meaning: wealth still isn’t distributed well in Chile), but also one of the most developed countries in the world.

Why would a dictator choose free-market policies remains unclear to this day. But Pinochet’s choice ultimately resulted in the stabilization of Chilean society and the overcoming of its worst crisis.

Indonesia, the Rise of a New Country

Pretty much the same thing that happened in Chile during the 1970s happened on the other side of the world in the newly-created Indonesia.

Ruled by a left-leaning president ever since its foundation in 1945, Indonesia was hit by a very confusing crisis on September 30, 1965, when a communist faction of the army was blamed for the death of six supposedly corrupt generals.

Whether there was a communist plan to kill these generals remains uncertain to this very day, but it is quite possible that it was all a ploy by one of the army’s mightiest generals, Suharto, because, just like in Nazi Germany in 1933, as soon as the ploy became public, he ordered the extermination of the communist element in Indonesia.

And, just like under Pinochet’s rule in Chile, that’s precisely what happened under Suharto’s rule: between half a million and two million communist supporters were killed by people who are now deemed liberators of the country (if you haven’t, watch the brilliant documentary, The Act of Killing, for more).

Suharto, as brutal and sadistic as he was, did employ a set of more moderate measures to fix Indonesia’s economy. Under the previous president, Sukarno, Indonesia aligned with China, but its economy was in shambles. Now it started making connections with the Western world. Unsurprisingly, Suharto too had his Chicago Boys. His economic team was dubbed, less courteously, the Berkeley Mafia.

Using foreign role models, the Berkeley Mafia successfully reduced Indonesia’s foreign debt and inflation, while balancing its budget, making the country a powerful international trading partner and global ideological player.

Once again, it was selective change by way of foreign role models that did the trick—even in the face of corruption and tyranny. Once again, a severe crisis was successfully overcome by using the knowledge garnered through similar experiences at some other places.

Rebuilding Germany

In 1945, Germany was not only covered in ruins but it was also divided in half. There was a reason for this, of course: the Allies believed that only a divided Germany would be unable to industrialize quickly and start another war.

However, just a few years after the war had ended, it was more than obvious to the United States that this was a risk it was willing to take because it was far more dangerous to leave the Soviet Union to expand its influence across Europe.

So, West Germany became part of the Marshall Plan, an American initiative to rebuild European economies after the war so that it could prevent the spread of communism.

The plan worked like a charm: from a country set back at least half a century, West Germany became the most highly developed European nation. It introduced a powerful new currency (the Deutsche Mark) and joined the free market both as one of the world’s topmost exporters and importers of goods.

When Willy Brandt became West Germany’s first left-wing chancellor, things took a turn for the better.

The reason?

Brandt was ready to stop playing the role of a victim and accept responsibility for Germany’s past sins. He apologized to neighboring countries and asked even Eastern bloc nations for forgiveness. At the same time, he supported American policies (including the Vietnam War) and was patient and flexible as far as the story of Germany’s reunification was concerned.

Eventually, in 1989, this happened, but it owes a lot to Brandt and the policies enacted during his reign.

Australia: Who Are We?

After the end of the Second World War, Australia faced one of the strangest crises a country can ever face.

You see, unlike Finland or Japan, Australia wasn’t interested in becoming an independent nation; on the contrary: it wanted to be part of the British Empire.

The problem was that the British Empire didn’t want to bother with Australia anymore. It simply disowned the country during the 1950s, reducing its military presence and opting to focus its trading interests on mainland Europe.

The Australians begged and begged and then realized that they had only themselves to rely on from now on. They couldn’t influence Britain’s decision, but they were able to do something about it. This was the first honest self-assessment of Australia.

It yielded some good results—the country started developing—but also some disastrous outcomes—its immigration minister, Arthur Calwell, was openly racist and was interested in accepting only white immigrants.

In 1972, when finally the Labor Party won, Australia made another honest assessment of itself and realized that it had to selectively change and become a country of its own.

First of all, since Britain was so far away, it had to improve its relations with its immediate neighbors, most importantly China. It also had to change its immigration policies and start accepting everyone: it needed people, and it needed them now. Finally, it needed to enact a policy of equal pay for women—for hundreds of obvious reasons.

The best example of selective change happened in 1999, when Australia finally recognized Britain as a foreign country, while symbolically still pledging allegiance to England’s Queen.

It lost something but not everything; and as it happens in the case of overcoming crises, what it lost was actually a gain in the long run.

Part 3: Nations and the World

In the third part, Diamond applies the lessons learned from the six crises described above to the current state of affairs in the United States and the world.

True, he says, just like Chile, Japan or Australia, the US is quite a unique country, and it is difficult to apply the lessons from other countries to one that has a pretty exceptional development, but he warns that many symptoms are there and that we must be careful lest we want to be mangled by a crisis of unforeseen proportions.

For, just like Chile, the United States is nowadays a deeply polarized country: for the first time in sixty years or so, people are severely divided along many lines—politically even more so than otherwise. In the absence of compromise, democracy is the first thing that suffers, so good people will have to either find a common solution or face the uncertainty and brutality of a totalitarian government.

It couldn’t happen here?

Well, that was the same thing Chileans thought until the beginning of the 1970s; and then they became a sadistic dictatorship.

Another thing that suggests that things are not going in the right direction in the US is the fact that, after the African-Americans were given the right to vote in the 1960s, governments are continually subverting people’s right to vote.

For example, the voter ID law requires every voter to have a current and valid photo ID to vote. However, in Texas, there are so few places that issue IDs or driver’s licenses that some people have to travel hundreds of miles to reach them.

Even worse, they work only during working hours, practically disqualifying the poorest people who can’t take a day off to travel to the nearest DMV.

Climate change is another thing the US doesn’t care one bit about, even though it is a scientific consensus that it is happening and that its results may be devastating.

For compassion, even though reducing consumption is a good way to tackle this problem, the US consumes twice the amount of oil per capita when compared to Western Europe, even though the quality of life is generally higher on the other side of the Atlantic.

Even scarier, it recently opted out of the Paris Agreement.

Diamond warns: that there are some issues that should not be left to the countries to solve but should be solved on an international, global level.

As Colin Kidd from The Guardian writes, “The prophet spares us chiseled commandments, but we have been warned.”

Indeed, we have.

Key Lessons from “Upheaval”

1. Individuals and Nations Have One Thing in Common: The Way They Overcome Crises

2. Overcoming Crisis Is All About Selective Changing

3. Other Nations’ Past Crises Can Teach Us a Lot About Current Problems

Individuals and Nations Have One Thing in Common: The Way They Overcome Crises

Almost all people, at a certain age or time (adolescence, the loss of a loved one, job loss, retirement, widowing, etc.) are bound to face a crisis. Be it internal (say, becoming sick) or external (being deserted by a spouse), an individual must change to some extent to overcome this crisis.

Therapists have developed “a road map of a dozen factors that help us to understand the varying outcomes” of an individual crisis. Interestingly enough, the same 12 factors seem applicable in the case of nations in crises.

Overcoming Crisis Is All About Selective Changing

Now, as we said above, an individual or a nation must change to some extent to overcome a crisis. However, the keyword in Jared Diamond’s book is “selective.”

He writes:

It’s neither possible nor desirable for individuals or nations to change completely, and to discard everything of their former identities. The challenge, for nations as for individuals in crisis, is to figure out which parts of their identities are already functioning well and don’t need changing, and which parts are no longer working and do need changing. Individuals or nations under pressure must take honest stock of their abilities and values. They must decide what of themselves still works, remains appropriate even under the new changed circumstances, and thus can be retained. Conversely, they need the courage to recognize what must be changed in order to deal with the new situation. That requires the individuals or nations to find new solutions compatible with their abilities and with the rest of their being. At the same time, they have to draw a line and stress the elements so fundamental to their identities that they refuse to change them.

Other Nations’ Past Crises Can Teach Us a Lot About Current World Problems

In Upheaval, Diamond analyzes six 20th-century crises: Finland’s Winter War with the USSR, the birth of Modern Japan during the Meiji era, the Allende/Pinochet years in Chile, the Sukarno/Suharto switch in Indonesia, Germany after the War, and Britain-less Australia of the second half of the past century.

The reason why he does this is quite simple: he believes that through these case studies, we can learn not only the ways in which a country can overcome a crisis but also the problems the world is facing nowadays.

A comparison with Chile of the 1970s, for example, reveals that the US may become a totalitarian country as well—if we are not careful.

And that’s a Jared Diamond warning.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Upheaval Quotes”

Crises, and pressures for change, confront individuals and their groups at all levels, ranging from single people to teams, to businesses, to nations, to the whole world. Click To Tweet Crises may arise from external pressures, such as a person being deserted or widowed by his or her spouse, or a nation being threatened or attacked by another nation. Click To Tweet Crises may arise from internal pressures, such as a person becoming sick, or a nation enduring civil strife. Click To Tweet Successful coping with either external or internal pressures requires selective change. That’s as true of nations as of individuals. Click To Tweet Crises have often challenged nations in the past. They are continuing to do so today. But our modern nations and our modern world don’t have to grope in the dark as they try to respond. Familiarity with changes that did or didn’t work in… Click To TweetOur Critical Review

Though Upheaval is as across-the-board and all-embracing as Guns, Germs, and Steel, it is much less rigorous and much more personal. Even so, it is once again a joy and a gem of a book.

“Though the analysis stumbles,” writes Moisés Naím in The Washington Post, “the virtues of Diamond’s storytelling shine through.” And he advises us to ignore Diamond’s “attempts to force the therapeutic 12-step onto history” or “his correct but unsurprising musings about the dangerous threats facing humanity.”Instead, he says, let the experienced observer that is Diamond “take you on an expedition around the world and through fascinating, pivotal moments in seven countries.” Upheaval— Naím elegantly concludes—”works much better as a travelogue than as a contribution to our understanding of national crises.”

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.