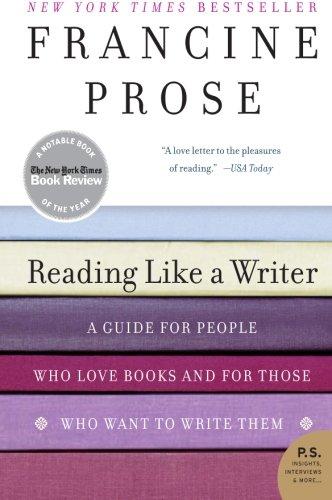

Reading Like a Writer Summary

14 min read ⌚

A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them

Want to write better?

Well, it all starts with reading better.

And Francine Prose is here to teach you how you can start:

Who Should Read “Reading Like a Writer”? And Why?

Reading Like a Writer is yet another manual for reading, not unlike Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren’s classic How to Read a Book and its more modern companion, How to Read Literature Like a Professor by Thomas C. Foster.

You can’t go wrong with either one of these three; though Francine Prose’s book is more personal than the other two, all of them are so great that we firmly believe that they might just work.

About Francine Prose

Francine Prose is an American novelist, essayist, and critic.

Visiting Professor of Literature at Bard College and a former president of the PEN American Center, she has authored 16 works of fiction and 8 nonfiction books.

Prose’s novel, Blue Angel, was a finalist for the National Book Award, and A Changed Man won the Dayton Literary Peace Prize.

Prose is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

“Reading Like a Writer PDF Summary”

Subtitled “A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them,” Francine Prose’s Reading Like a Writer is essentially a Reading 101 textbook for everyone who wants to become a poet or a novelist – or thinks that he/she is one at the moment.

A sort of a personal journey through the world of books (and especially those who made Prose the writer that she is today), the book is filled with examples from literary masterworks and even includes a list of “books to be read immediately” for anyone interested at the end.

Let’s summarize it, chapter by chapter (each of which deals with a different aspect of the writing craft, starting with words and ending with, well, the master of masters, Chekhov).

Chapter One: Close Reading

Do you know how most of the great artists you’ve grown to admire throughout the years acquired and perfected their craft?

The simplest answer: they spent years studying and imitating the works of their predecessors.

So why should literature be any different?

Instinctively, it may be not.

After all, children read slowly, mouthing almost every word they encounter upon a page. Unlike them, adults seem to only know how to read fast.

In fact, that’s often their very goal: skim-reading!

In Prose’s belief – which we full-heartedly share – the difference between a slow reader and a fast one is the difference between a refined gourmet and a junk-food eater.

Simply put, you won’t feel all the flavors in the latter-case scenario, and, to use another analogy we’ll get back to in our summary of the last chapter, you’ll probably mistake a rose for a weed.

The solution?

Pay closer attention.

Approach great books as you would riddles: they hide layers of meaning, meaning their authors want you to break some sweat and discover at least some of them, the way Redditors do when they hunt for TV show’s Easter eggs.

For example, Shakespeare’s King Lear and, especially, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex are much, much better books if, in addition to the story, you focus on the motifs of blindness and seeing.

Prose experienced this when she was a 16-year-old student given this very assignment.

“It was fun to trace those patterns and to make those connections,” she writes. “It was like cracking a code that the playwright had embedded in the text, a riddle that existed just for me to decipher.”

Suddenly, the “reading better makes you a better writer” idea doesn’t sound that strange, does it?

Chapter Two: Words

There are hundreds of thousands of words in the English language.

About half a million according to Wikipedia.

How much is that, you wonder?

Well, consider the fact that the full number of entries in the multi-volume OED is merely a half of that.

Why is this important?

Well, because writers work with words and not paying close attention to all of them – aka skim-reading them – is not too dissimilar from listening just the first minute of a song, then skipping to the third one and listening to a few seconds and then to the last 20 seconds.

In Prose’s words:

With so much reading ahead of you, the temptation might be to speed up. But, in fact, it’s essential to slow down and read every word. Because one important thing that can be learned by reading slowly is the seemingly obvious but oddly underappreciated fact that language is the medium we use in much the same way a composer uses notes, the way a painter uses paint. I realize it may seem obvious, but it’s surprising how easily we lose sight of the fact that words are the raw material out of which literature is crafted.

In other words, if you want to read – read all of the words.

As Fry and Laurie taught us, there are countless of word-combinations and, for some reason, some authors have made the decision to use a certain one (and not another).

Your job?

Compel yourself to reading each and every word on a page by asking yourself what sort of information each word – i.e., each word choice – is conveying.

It’s slow – we know.

But that’s the point.

Chapter Three: Sentences

Now, words form sentences, so the next level of reading is that of the sentence.

“The well-made sentence,” writes Prose, “transcends time and genre. A beautiful sentence is a beautiful sentence, regardless of when it was written, or whether it appears in a play or a magazine article.”

But how you should find one, or, if you are a writer, compose one?

Is it supposed to be a short one or a long one? Does it need to be alliterative and lyrical or impartial and, to use a word Hemingway famously uses in A Moveable Feast, true?

If you’re looking for a straightforward answer, don’t look for it in this book!

There are numerous writers who became famous because of their mastery of short sentences (Hemingway being the most famous example) and many others who became the object of admiration because of their meandering, indescribably beautiful 100+ word sentences (Marcel Proust, we’re looking at you!)

Also, there are some sentences which sound even more lyrical than verses (remember the concluding ones of James Joyce’s “The Dead”), and some others which, though long and objectively written seem as clear and as precise as Hemingway’s five-word sentences (Prose offers as an example the opening of Heinrich von Kleist’s story “The Earthquake in Chile”).

But, then, there’s one thing you can do to make your sentences sound sweeter and more majestic.

Read your work aloud.

“Chances are that the sentence you can hardly pronounce without stumbling,” writes Prose, “is a sentence that needs to be reworked to make it smoother and more fluent.”

Also, if a thief breaks into your apartment while you’re doing this, he/she will probably run away thinking you a madman.

True story.

Chapter Four: Paragraphs

If words form sentences, sentences form paragraphs; and paragraphs are not merely the building blocks of a story, but also its DNA, the author’s fingerprints on his/her work:

A clever man might successfully disguise every element of his style but one – the paragraphing. Diction and syntax may be determined and controlled by rational processes in full consciousness, but paragraphing – the decision whether to take short hops or long ones, and whether to hop in the middle of a thought or action or finish it first – that comes from instinct, from the depths of personality. I will concede the possibility that the verbal similarities, and even the punctuation, could be coincidence, though it is highly improbable; but not the paragraphing. These three stories were paragraphed by the same person.

Now, that paragraph is not written by Prose, but by Rex Stout and comes from one of his Plot It Yourself mysteries; it is uttered by the detective Nero Wolfe when tasked with finding out if three manuscripts are plagiarized by one and the same person.

Apparently, in his view, they must be, because we write paragraphs too instinctively to falsify them; Proust believed that a writer’s style embeds his/her vision of the world; and, style, Stout adds, is made of paragraphs.

Prose’s piece of advice when it comes to paragraphs?

Think of them as a kind of literary breathing.

Too many short paragraphs make your text asthmatic; too many long ones will make your reader breathless (in the worst possible way).

Chapter Five: Narration

On to narration and narrators!

The best rule of thumb: use first-person or third-person narration and an interesting narrator.

Notice how we highlighted the word interesting?

It’s because that’s all it takes: the narrator needs to intrigue your readers, and it doesn’t matter if he’s someone you wouldn’t hang out with in real life.

In fact, more often than not, these are the most interesting narrators.

Consider the beginning of Lolita:

“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins, My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta. She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.”

Now, the speaker of these words is a lunatic enamored with an underage girl; in real life, Humbert Humbert probably belongs in prison.

But, in the world of literature, he’s exactly the kind of guy you’ll be interested in knowing more about.

He may be a lunatic, Prose says, but he is a “brilliant, inventive, self-dramatizing, self-mocking, obsessive lunatic genius.”

And who wouldn’t want to get to know one when there’s no danger lurking around the corner (except for papercuts)?

Chapter Six: Character

Unless a peculiarity, a novel can’t exist without characters, and the characterization of one can be done via one or all of these ways: through his/her actions, thoughts, and words.

Chapter seven is dedicated to the last of the three, and in this chapter, Prose compares the method of Heidrich von Kleist with that of Jane Austen to demonstrate how one can master the first two.

“Among the unusual things about the way that Kleist creates his characters,” Prose writes analyzing Kleist’s novella The Marquise of O, “is that he does so entirely without physical description.”

“There is no information, not a single detail, about the Marquise’s appearance,” she goes on. “We never hear how a room looks, or what the latest fashion might be, or what people are eating and drinking. We assume that the Marquise is beautiful, perhaps because her presence exerts such an immediate and violent effect on the Russian soldier that he loses all control and turns from an angel into a devil. But we can only surmise that.”

In a word, Kleist “tells us just as much as we need to know about his characters, then releases them into the narrative that doesn’t stop spinning until the last sentence.”

On the opposite side of the spectrum, Jane Austen (no need introducing her), introduces us to her characters by telling us almost everything about them.

“In Kleist,” concludes Prose, “characters tend to be defined by their actions. But Austen is more likely to create her men and women by telling us what they think, what they have done, and what they plan to do.”

Chapter Seven: Dialogue

How many times have you heard literature professors and creative writing teachers advising you to clean up and polish your dialogue?

Fictional dialogue can’t sound like actual speech, they say:

The repetitions, meaningless expressions, stammers, and nonsensical monosyllables with which we express hesitation, along with the clichés and banalities that constitute so much of everyday conversation, cannot and should not be used when our characters are talking. Rather, they should speak more fluently than we do, with greater economy and certitude. Unlike us, they should say what they mean, get to the point, avoid circumlocution and digression. The idea, presumably, is that fictional dialogue should be an ’improved,’ cleaned-up, and smoothed-out version of the way people talk. Better than ‘real’ dialogue.

“Then why,” asks Prose, “is so much written dialogue less colorful and interesting than what we can overhear daily in the Internet café, the mall, and on the subway?”

You know why?

Because of advices such as the one above.

Just like psychotherapists, readers should train themselves uncovering secret meanings even beneath the surface of banal words.

If you feel like your character would use them – then let him use them.

Dialogue should always provide both text and subtext, “allowing us to observe the wide range of emotions that [your] characters feel and display, the ways in which they say and don’t say what they mean, attempt to manipulate their spouses, lovers, friends, and children, stake emotional claims, demonstrate sexual interest or unavailability, confess and conceal their hopes and fears.”

Yup: that much is at stake.

Chapter Eight: Details

True, many authors (including Prose) claim that in a literary work, every word matters and counts. But they forget to add that it doesn’t matter and count in the same manner.

Put simply, some words reveal more than it seems that they do on the surface; however, others, reveal nothing, but are meant to leave a memorable impression of the “why would this author mention something like this?”

Here’s a great example:

In one case (Mark 8:22-26), Jesus makes a blind man see from the second attempt. The first attempt obviously fails, since, after it, the blind man of Bethsaida sees men “like trees, walking.”

Now, many theologists ask (and this is called the criterion of embarrassment), why would Mark write something like that if it wasn’t true?

Regardless of whether you believe in the Bible or not, a great answer is this: because the writer knew people would ask questions such as the one above.

That’s what all liars know and, in a way, writers are not that dissimilar from liars.

If you want to be a good one, be mindful of the details – and include at least a few which would make your readers ask: “now, why would he/she mention something like this?”

Chapter Nine: Gestures

Another important type of detail in a literary work is a character’s gestures.

For example, consider the brilliant Katherine Mansfield short story “The Fly.”

In it, the protagonist, called merely “the boss,” is visited by a friend, Mr. Woodifield, who happens to inadvertently mention the protagonist’s son’s grave; the boss’s son, we learn, was killed six years before this meeting in the First World War, “a death the boss never mentions and tries not to think about.”

Stricken with anguish, but (to his surprise) unable to shed a single tear, soon after Mr. Woodifield leaves, the boss notices a fly fallen into his inkpot.

He rescues it, watches it dry, and then drops a blob of ink onto it; and then, after some time, another; and then, finally, a third one; the fly struggles through it all, but is unable to survive the third drop.

It’s easy to interpret this gesture over-simply, writes Prose: the boss’s grief has moved him to do violence to a harmless fly.

However, “the delicate shifts in the boss’s emotions and his responses to the fly’s struggle move us beyond this surface reading to consider the distractions of casual cruelty, the pleasures of playing god as a means of mediating one’s own sense of powerlessness, and the perverse desire to pass pain on to anyone – anything – who is weaker and more helpless than we are.”

What a gesture, ha?

Hunt for such illuminative acts – and ignore all “physical clichés.”

Chapter Ten: Learning from Chekhov

You need a writer to learn from the craft of writing?

There’s one: it’s not Shakespeare or Tolstoy or Goethe or Dante.

It’s Chekhov, the greatest short story writer of all time (according to many writers), one whose sentences will make you think that maybe things aren’t so bad after all, an author whose works (and almost all of them, mind you!) are “not only profound and beautiful, but also involving.”

Reading Chekhov, I felt not happy, exactly, but as close to happiness as I knew I was likely to come. And it occurred to me that this was the pleasure and mystery of reading, as well as the answer to those who say that books will disappear. For now, books are still the best way of taking great art and its consolations along with us on a bus.

Chekhov can teach you to write without judgment – i.e., be the unbiased observer – and to break the “rules” of writing when rules are meant to be broken.

Plus: there’s no way you’re not going to enjoy his short stories.

And, quite perhaps, be irretrievably moved and changed by at least a few of them.

Chapter Eleven: Reading for Courage

It’s scary to put yourself out there at the mercy and mercilessness of other people; that’s why actors have stage fright, and that’s why writers are afraid of the blank page.

And then there’s also the inevitable fear of pointlessness: to paraphrase Broch, is it not inhumane to care about whether the word you’ve selected or the sentence you’ve constructed is beautiful when there are about 2 billion poor people around today?

As far as Prose is concerned, you need to dispel those fears: there’s always a point in planting more roses in this world.

And reading is a way to see how other rose-growers grow their roses.

“If we want to write,” Prose ends her book, “it makes sense to read – and to read like a writer. If we wanted to grow roses, we would want to visit rose gardens and try to see them the way that a rose gardener would.”

Books to Be Read Immediately

In one final chapter, Prose includes a long list of book recommendations; there’s no point in copying it here since you can find the entire list on Wikipedia.

So, what are you waiting for?

Key Lessons from “Reading Like a Writer”

1. Language Is the Medium of Writers

2. There Is No Such Thing as Fast Reading

3. Slow Readers Make the Best Writers

Language Is the Medium of Writers

True, this lesson sounds both banal and trivial, but somehow it is still an “oddly underappreciated fact.”

Why would Prose think that?

Well, simply put, because if you really believed that words are to writers what notes are to musicians and paint is to painters, then you wouldn’t read so fast!

There Is No Such Thing as Fast Reading

How do you know when you’re really enjoying a song?

Well, for one, you don’t skip a beat.

That’s what you do all the time when you’re reading.

The truth is, if so, you’re not reading at all.

You’re actually just watching a movie on fast-forward, not immersing yourself within the experience nor actually learning anything.

Slow Readers Make the Best Writers

Want to become a better writer?

Well, then, start reading slowly.

Savor every word, analyze every sentence, follow motifs and symbols, jot down your notes on the margins of interesting paragraphs.

Also, read aloud every single word you’ll ever write.

If it doesn’t sound good enough when you hear it, then probably it isn’t.

“I’ve often argued that the only skill any writer needs,” writes Oxford Professor of Poetry Simon Armitage in an article on Bob Dylan for The Guardian, “is the ability to see his or her work from the other side. That is, to put him or herself in the position of the reader.”

Francine Prose feels pretty much the same.

Like this summary? We’d like to invite you to download our free 12 min app for more amazing summaries and audiobooks.

“Reading Like a Writer Quotes”

I’ve always found that the better the book I’m reading, the smarter I feel, or, at least, the more able I am to imagine that I might, someday, become smarter. Share on X Like seeing a photograph of yourself as a child, encountering handwriting that you know was once yours but that now seems only dimly familiar can inspire a confrontation with the mystery of time. Share on X The truth is that grammar is always interesting, always useful. Mastering the logic of grammar contributes, in a mysterious way that again evokes some process of osmosis, to the logic of thought. Share on X Reading your work aloud will not only improve its quality but save your life in the process. Share on X If we want to write, it makes sense to read—and to read like a writer. If we wanted to grow roses, we would want to visit rose gardens and try to see them the way that a rose gardener would. Share on XOur Critical Review

Reading Like a Writer is both a Reading 101 manual and a very personal love letter to books.

“Prose’s little guide will motivate ‘people who love books,’” notes a New York Times book review. “Like the great works of fiction, it’s a wise and voluble companion.”

“A jewel of a companion,” adds Los Angeles Times.

And they are more than right.

Emir is the Head of Marketing at 12min. In his spare time, he loves to meditate and play soccer.